Recently i stumbled upon a survey in some posh English art magazine. The journalist was asking readers whether they had already travelled only to see an exhibition in a foreign country. As you can guess i ticked the box “Yes, at least once a year.” If there had been a question asking “Have you ever travelled just to see one single piece in an exhibition?” I would have answered “Yes, i did that once.” It was in 2005, i took the plane to Paris just to see one work in the exhibition D.Day Modern Day Design at the Centre Pompidou. It was Fiona Raby and Tony Dunne‘s Evidence Dolls. The dolls are hypothetical products that could be used by single women to store DNA samples from potential partners, gaining thus an increased sense of control in the dating game. Any reason to go to Paris is always welcome anyway.

Recently i stumbled upon a survey in some posh English art magazine. The journalist was asking readers whether they had already travelled only to see an exhibition in a foreign country. As you can guess i ticked the box “Yes, at least once a year.” If there had been a question asking “Have you ever travelled just to see one single piece in an exhibition?” I would have answered “Yes, i did that once.” It was in 2005, i took the plane to Paris just to see one work in the exhibition D.Day Modern Day Design at the Centre Pompidou. It was Fiona Raby and Tony Dunne‘s Evidence Dolls. The dolls are hypothetical products that could be used by single women to store DNA samples from potential partners, gaining thus an increased sense of control in the dating game. Any reason to go to Paris is always welcome anyway.

If you follow the blog, you must be familiar with the work, and writing of Dunne & Raby.

Dunne is the Head of Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art in London. As demonstrated during the recent Work in Progress Show of Design Interactions students, the focus of the department is shifting. While electronics and computing remain essential elements of the course, his students are also exploring how design can connect with other technologies, such as biotechnology and nanotechnology. The result is a wide range of projects, often speculative and critical, which aim to raise the debate on the human consequences of different technological futures.

I actually first thought this interview for World Changing (where it’s been posted… with a less lazy introduction) and i realize now that if i had prepared the piece for wmmna, the questions would have been slightly different. But mister Dunne is a busy man, i couldn’t ask him to face two interviews, could i?

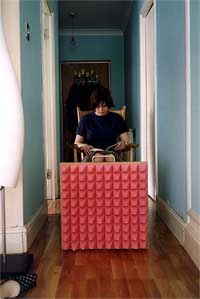

Placebo: The Electro-draught Excluder and the Nipple Chair

Placebo: The Electro-draught Excluder and the Nipple Chair

Your works express the belief that design shouldn’t just be used to turn technology into something eye-pleasing, sexy and easy to use. What other role should design play then?

It could make us think and encourage us to ask more from industry! There is no need to rush into the future frantically styling up new technology and getting it to market as fast as we can. We need to reflect a bit more and ask some questions, I know this is completely at odds with the industrial system we have today, but I think as a profession we could take on more social responsibility and use some of our time, resources and know-how to explore alternative ideas about everyday life to those put forward by industry.

I think there is a real need for design to address the public as well as industry, and to explore new ways of getting discussions going about what people really want and how industry can help us achieve it, rather than the other way around.

Teddy blood bag and Meat eating products

Teddy blood bag and Meat eating products

Your installation about future energy sources at the Science Museum in London is extremely surprising. The scenarios you picture there are deeply grounded in scientific research, yet they are miles away from our dreams of solar-powered cars and hydrogen-based cities: “poo” is envisioned as a resource, a radio is fuelled by blood kept in cute teddy-shaped pouches, and churches, school, even families are developing their own energy brand. Why didn’t you follow the trend and show more positive and bright visions of the future?

The exhibit is aimed at children between the ages of 7 and 12. Everywhere they look they will see images showing how bright our technological future will be once we embrace new energy sources like Hydrogen. But things are not so simple, with every new technology there are of course other consequences — economic, cultural and ethical. With this project we wanted to encourage children to think about the implications of 3 different technologies, all real, but some more likely to happen than others. The first is Hydrogen, here we wanted to deal with economics by portraying a scenario children could relate to — having to produce a certain amount of hydrogen in order to get their pocket money. Human Poo as energy was about a major cultural shift where something once thought of as dirty would become valuable, so people would want to keep it, disconnect themselves from the sewage system and even offer it as a gift. And with the blood scenario, we wanted to show that often, reality is stranger than fiction, there is a growing area of research looking at how microbial fuel cells can be used to make self-sufficient robots and other products; pacemakers that run on the blood in our own bodies for example. In this case we wanted children to think about ethics: where would the blood come from? Of course we slightly exaggerated everything to make them more engaging.

Why do you think that biotechnology, synthetic biology or nanotechnology, like electronics, are areas in which design should play a role?

All of these technologies, separately, and in combination, are going to have a huge impact on our lives in the near future. I think it’s important that designers, start thinking about how to get involved. It’s not just about new skills or a new medium, but very different ways of thinking. What does it mean to design living or semi-living materials and products? It’s important too that design, with its powerful visualisation skills, makes abstract concepts tangible and discussable. It can help us debate different futures before they happen. Otherwise the ‘future’ is just going to happen to us and the products and services we get will be driven by economic and technological factors rather than human needs, let alone desires.

I think it would be a great shame if designers stayed on the margins while these technologies begin to shape the world around us. The time it takes for science to turn into technology and then products is speeding up. There is no comparison with the trajectory electronics took so we need to start getting involved now and exploring what impact these new technologies will have on our lives.

Interaction Design grew out of the meeting of digital and cultural worlds and the need to make computers more useable, it will be interesting to see what other forms of design will emerge over the coming years.

Can you give us one example of a student(s)’ project that best represent the “design for debate” approach?

I think the best example has to be Tobie Kerridge and Nikki Stott’s Biojewellery, partly because it has evolved so much over the last 3 years. They started it in response to the first bio brief we set at the RCA in 2003. Later, with bioengineer Ian Thompson, they followed it through to a really impressive level. I particularly like some of the documents they produced on the way exploring the ethics of the project and whether or not it would be OK to operate on someone for basically poetic reasons. The project has generated debate and discussion throughout its life at all levels — aesthetics, practicalities, business, design, methodology … I don’t think all projects need to reach this level of resolution to be successful, but it’s a good example of what’s possible.

Test samples and Previous prototype of a ring using a combination of cow marrow-bone and etched silver

Test samples and Previous prototype of a ring using a combination of cow marrow-bone and etched silver

Two years ago, you showed Evidence Dolls at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The plastic objects were created to provoke discussion amongst a group of single women about the impact of genetic technology on their lifestyle. Can you tell us more about that project?

What was the impetus for this project?

Valerie Guillaume, a curator at the Pompidou Centre was very keen to have something about critical design in an exhibition she was curating so she commissioned the project. We had already sketched out the idea in BioLand and we thought this was a nice opportunity to take the idea further and also explore how it could be used to produce some new insights.

In the projects we ran with students about biotech, there would always be something to help men avoid leaving DNA behind so that they wouldn’t be implicated in future paternity cases. We, well Fiona, thought the woman’s perspective should be represented too. We were inspired by the story of a famous English actress who hired a detective to rummage through an ex-lover’s bin looking for material that could be analysed for DNA and used to prove he was the father of her baby. The detective found some dental floss and it provided enough DNA to prove he was the father. Fiona thought this process should be made a little easier. The doll is effectively a storage device for DNA from a woman’s various lovers. It would be collected in the form of toenail clippings, hair and other bodily materials. Later, if necessary, they could be analysed. The material is stored in a S,M or L penis drawer. The dolls can be personalised to represent each lover. For the exhibition we worked with ÅBÄKE who interpreted the interview transcripts through drawings on each doll. the interviews with the women were included in the exhibition.

In the projects we ran with students about biotech, there would always be something to help men avoid leaving DNA behind so that they wouldn’t be implicated in future paternity cases. We, well Fiona, thought the woman’s perspective should be represented too. We were inspired by the story of a famous English actress who hired a detective to rummage through an ex-lover’s bin looking for material that could be analysed for DNA and used to prove he was the father of her baby. The detective found some dental floss and it provided enough DNA to prove he was the father. Fiona thought this process should be made a little easier. The doll is effectively a storage device for DNA from a woman’s various lovers. It would be collected in the form of toenail clippings, hair and other bodily materials. Later, if necessary, they could be analysed. The material is stored in a S,M or L penis drawer. The dolls can be personalised to represent each lover. For the exhibition we worked with ÅBÄKE who interpreted the interview transcripts through drawings on each doll. the interviews with the women were included in the exhibition.

And how did the women understand, react to and welcome this unconventional project?

This was all done behind closed doors. As you can imagine, the conversations were quite intimate as each woman spoke candidly about her past lovers. But most of the women reacted to it as something they could imagine using, I found this strange to believe myself, but that was the reaction. The project was not about whether they would want or even use one, it was more about finding a way to explore the impact a new technological possibility might have on ideas of love, romance and dating.

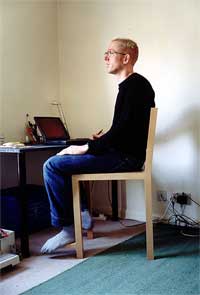

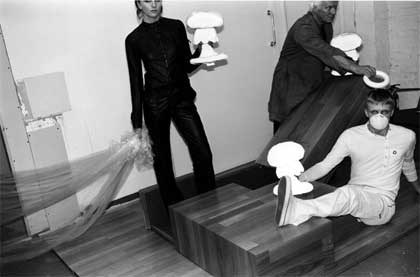

Anxious Times: Hideaway Furniture, Huggable Atomic Mushroom

Anxious Times: Hideaway Furniture, Huggable Atomic Mushroom

You’re now Head of the department of Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art in London. A year ago, the department was still called Interaction Design. What motivated such change?

The name interaction design is beginning to mean something quite specialised and focussed on designing interfaces for electronic and digital products and systems. This is probably a very good thing if you are trying to establish a discipline or a group within a company, but it’s not so good if you are interested in pushing boundaries and exploring new ways designers can make technology relevant and meaningful to everyday life. Designing better interfaces is one way of doing this but not the only way.

I think originally, the interesting thing about interaction design was the emphasis on designing interactions rather than things. We changed the name of the department around to emphasise this. But by changing the name we also hoped to decouple interaction design as a design approach, from purely digital and electronic technologies, and to allow it to continue to mutate and evolve in relation to design challenges created by a whole range of other technologies like bio- and nanotech as well as new social and cultural developments.

Our intention is to broaden the technological focus of the department so that new design contexts, methods and roles can begin to emerge, and possibly, even provide new perspectives on how we design interfaces for digital technologies.

To work in such and open space can be quite challenging and students need to have a very strong sense of self, but we think that ultimately, this will prepare designers for working at the cutting edge of a very fluid and exciting area of design.

Your students work closely with people outside the College, some of them are scientists. Or do these scientists see this “intrusion” of designers into their own sphere of research?

This is something we are still evolving. The scientists we have met so far are all dedicated to engaging with people outside science and have been very enthusiastic about student work. I’m sure there are scientists who would see us as intruders, but I doubt we will meet them very often, I think we are moving in different circles and networks.

Which (work) future do you see for students who want to fully engage in “design for debate”?

Often, when I give a lecture and show work from the design for debate projects, designers find it a bit too weird and extreme or try to label it as art rather than design (to defuse it), but always, there are people in the audience who come up afterwards to talk about commercial possibilities and see it simply for what it is, a way of getting a discussion going about the impact technology might have on everyday life by imagining positive and negative future scenarios.

The Design for Debate project is only one of 6 we run in first year each exploring different design approaches, roles and contexts but it produces some of the most striking results. I think for most students it’s an interesting learning experience, but I’m not sure how many of them plan on taking this approach further when they graduate. For those who do, I think there are several possible directions. The most natural is the exhibition route, showing in various venues and crossing between art and design worlds. But other possibilities are emerging.

Last summer, two of our students did internships in the Department of Trade and Industry‘s Foresight Group working with scientists and civil servants on a project about obesity. The students enjoyed it and the DTI wants more this year. So there also seems to be a place in organisations, government or otherwise, for this kind of design. Companies like Philips are very interesting, they have a small group looking at the cross over between biological and electronic systems in relation to new products and interfaces, and I could see possibilities there which I guess are more research orientated. They do projects called probes which are intended to provoke and open up new possibilities, design for debate projects would prepare students well for this role. And then there are all the yet to be discovered possibilities.

ARK-INC installation at the 2006 RCA Summer Show

ARK-INC installation at the 2006 RCA Summer Show

Last year, at the RCA Summer show, one of your students presented a project that i liked a lot, it was called Ark Inc. Jon Ardern looked at our ineffectual attempts to live a truly sustainable life. His project suggested that we adapt our life style to life “after the crash”, to the time when our actions have exhausted the resources of the Earth upon which we depend. Can you comment on this particular project?

Only that I really like it. I think it’s very interesting to design organisations as well as systems and services and Jon worked hard to avoid the usual forms of ‘evidence’ these projects can generate. One thing we struggle with is how to communicate work like this in a show with 200 other designers. Having said that, you found it and enjoyed and I know many others who did too, but it would be good to reach a wider audience with work like Jon’s. We have two students this year building on Jon’s approach one is looking at “11 solutions to an impending apocalypse“, and the other is designing communication and other systems for a group of extreme eco-guerillas that places the survival of the planet above all else.

What are you working on now?

Well the new course is taking up a lot of my time, but besides that we are working on a few new things. We did a small project for an exhibition at the Science Museum about spying which we enjoyed working on, Noam Toran, Troika, and Onkar Kular did some work for it too.

We’re working on a collection of electronic prototype products with Michael Anastassiades that extends the Fragile Personalities project into the electronic realm for an exhibition in October, and we’ve just finished some work for an exhibition at z33 in Hasselt, called Designing Critical Design that’s just opened. We are showing with two designers whose work we really like, Marti Guixe and Jurgen Bey. It consists mainly of existing work but the curators have commissioned some new work as well which I will say a little about as we really enjoyed doing it.

After a trip to Tokyo in November we became very interested in Robots and developed some conceptual products for the show, as well as a video with Noam Toran and some sounds with Scanner.

All the robots (Image by Per Tingleff)

All the robots (Image by Per Tingleff)

Robots are destined to play a more significant part in our daily lives over the coming years. But how will we interact with them? What kind of new interdependencies and relationships might emerge? The objects we developed are meant to spark a discussion about how we’d like our robots to relate to us: subservient, intimate, dependent, equal? We presented 4 ideas.

Robot 1: This one is very independent. It lives in its own world getting on with its work. We don’t really need to know what it does as long as it does it well. It could be running the computers that manage our home. It has one quirk; it needs to avoid strong electromagnetic fields as these might cause it to malfunction. Every time a TV or radio is switched on, or a mobile phone is activated it moves itself to the electromagnetically quietest part of the room. As it is ring shaped, the owner could, if they liked, place their chair in its centre, or stand there and enjoy the fact that this is a good space to be in.

Robot 2: In the future products/robots might not be designed for specific tasks or jobs. Instead they might be given jobs based on behaviours and qualities that emerge over time. This robot is very nervous, so nervous in fact, that as soon as someone enters a room it turns to face them and analyses them with its many eyes. If the person approaches too close it becomes extremely agitated and even hysterical. Home security might be a good use of this robot’s neurosis.

Robot 3 and Robot 4

Robot 3 and Robot 4

Robot 3: More and more of our data, even our most personal and secret information, will be stored on digital databases. How do we ensure that only we can access it? This robot is a sentinel, it uses retinal scanning technology to decide who accesses our data. In films iris scanning is always based on a quick glance. This robot demands that you stare into its eyes for a long time, it needs to be sure it is you.

Robot 4: This one is very needy. Although extremely smart it is trapped in an underdeveloped body and depends on its owner to move it about. Originally, manufacturers would have made robots speak human languages, but over time they will evolve their own language. You can still hear human traces in its voice.

During this project we also became very interested in microbial fuel cells that use bacteria to break down ‘food’ such as slugs, meat, rotten apples and flies. In the future, some robots will have stomachs. How will the way we interact with them be affected when we have to feed them rather than recharge them?

And finally, I think our big interest right now is exploring how a critical design approach can be applied to future scenarios and emerging technologies in relation to public engagement and debate, this work is more theoretical and ongoing, and hopefully, will eventually result in a new book.

Many thanks for your time, Tony!

You’re welcome, and thank you for your questions.

Images from the websites of Raby & Dunne, Design Interactions, Jon Ardern, pictures of the robots by Per Tingleff.

Look out for their books:

Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects by Fiona Raby and Anthony Dunne (UK – USA)

And the recent re-edition of Anthony Dunne’s Hertzian Tales – Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design.