Atlas of Borders. Walls, Migrations and Conflict in 70 Maps, by Delphine Papin, head of the infography and Cartography department at Le Monde newspaper, and Bruno Tertrais, deputy director of the Foundation for Strategic Research and the Associate Expert at the Institut Montaigne. Maps by cartographer, journalist and infographic designer Xemartin Laborde.

An Atlas of Borders seems like an absurdity when the most powerful man in the world has launched a campaign of imperial populism that goes from narcissistically changing the name of the Gulf of Mexico to threatening to absorb various autonomous territories. Orange monsters might not care about borders, but an atlas that maps and analyses them makes even more sense now than ever.

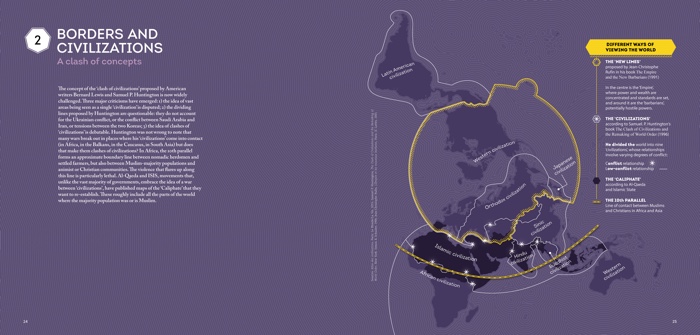

Across the globe, wars, pandemics, nostalgia for fallen empires, cyber attacks, global warming are contesting, redefining, breaking or reinforcing borders. When every crisis, every discovery can spark a border dispute, an atlas can help us make sense of complex spatial information, identify patterns and relationships and understand geopolitical tensions.

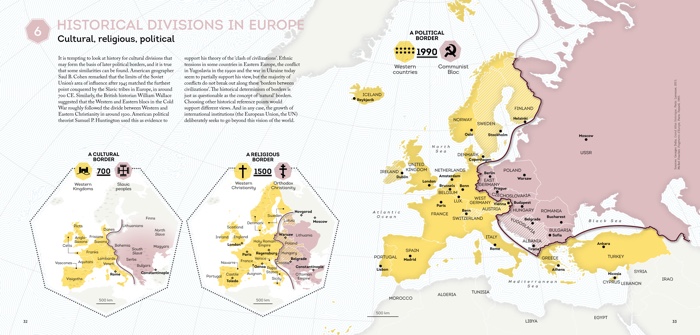

The book reveals how land and marine borders are rarely neat separations between nations. Far from being purely “natural,” they often bear the marks of arbitrariness and legacy from the past.

In Islamic tradition, for example, the outer border of Dar al-Islam was temporary and state borders within it were unlawful. I also discovered in the atlas that, up until the 19th century, it was easier to enter a national territory than to leave it. Departure raised suspicions: were you fleeing conscription or evading taxes? Today, the opposite is true.

The emergence of borders as we know them emerged alongside the modern world. They developed along with modern cartography and are the object of regular negotiation. In some parts of the world more than others. The “lines” of South Asia, drawn up by British colonisers, are among the most contentious on the planet. Even the external contours of “Fortress Europe” remain uncertain. Greece and Turkey, for example, have yet to define their maritime borders. Morocco continues to claim Perejil Island. And you can find European overseas territories on other continents.

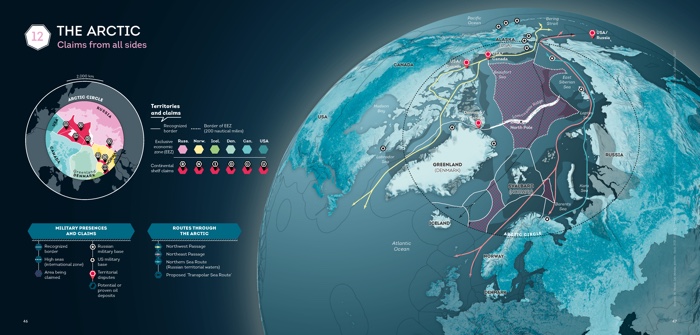

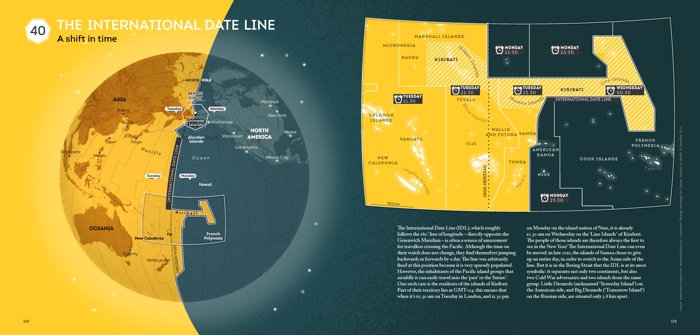

The atlas is packed with fascinating discoveries. I knew of the Iron Curtain but had never heard of the Cactus Curtain, the Bamboo Curtain or the Banana Hole. I also learnt that, for centuries, the reach of a cannonball fired from the coast (nautical miles) dictated maritime borders. Or that determining whether the Caspian Sea is a sea, a lake or something in between has implications for the exploitation of resources and water management.

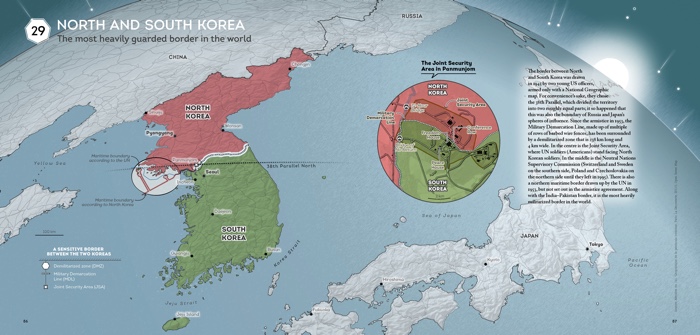

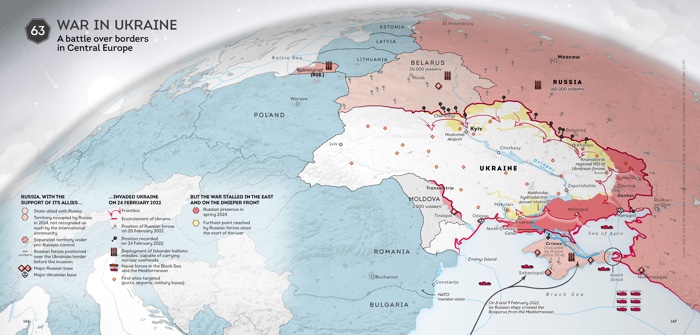

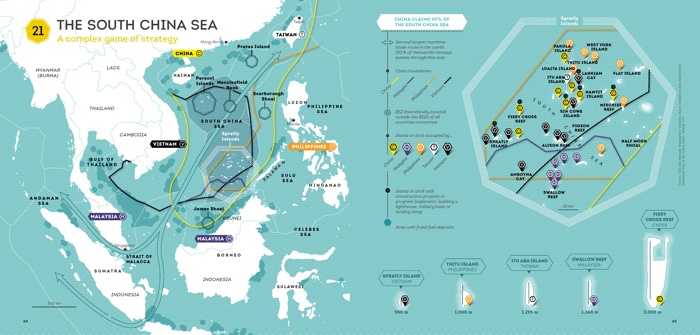

Even more interestingly, the 70 maps and their accompanying short texts expose the background of ongoing major territorial conflicts: Azerbaijan’s brutal incursions in Nagorno-Karabakh, piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, the 2000 km long wall in Western Sahara, Guyana’s dispute with Venezuela over the (fossil fuel-rich) region of Essequibo, the buffer zone between India and Bangladesh, Israel’s rabid politics of illegal land grabbing, etc.

The maps dedicated to the neo-empires are as fascinating as they are unsettling. While we’re all horrified by Trump’s efforts to colonise mineral and fossil fuel-rich areas, Türkiye, Russia and China are devising legal and illegal ways to stretch their dominion across land and sea.

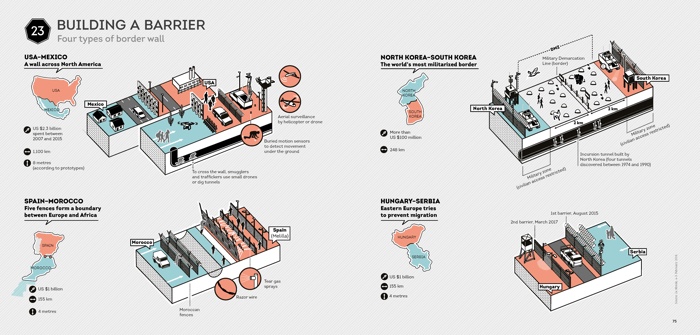

Looming geopolitical turmoils suggest a prosperous future for (the industry of) walls and fences. Whether they are physical or virtual and made of highly advanced surveillance technologies. We can expect more disputes over the delimitation of maritime territories. Another trend that the authors of the atlas have identified is the “privatisation of borders”. The increasingly expensive physical management of borders is often delegated to private companies or even other nations.

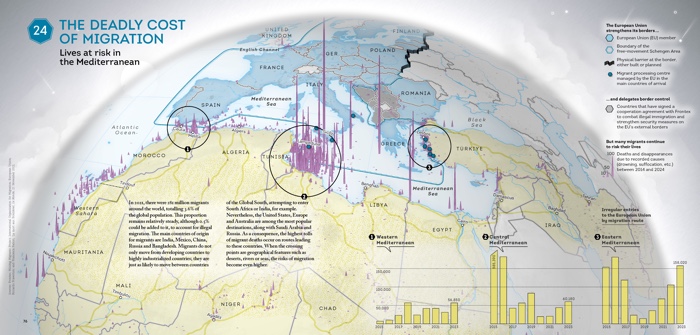

In parallels to this segmentation of the globe, calls for a world without borders are growing louder. Walls, the authors explain, are more popular with politicians than with philosophers. Thierry Paquot even declared that “the builder of a wall is a polluter of humanity”. On a planet where pandemics, climate collapse, pollution, long range missiles and cyberattacks disregard walls, more effective cross-border cooperation is not just idealistic, it is essential. In addition, as some of the maps in the Atlas describe, the consequences of looking for alternatives to borders can be deadly: the number of deaths by drowning (in the Mediterranean) and dehydration (in Arizona) has risen significantly in recent years.

However, Delphine Papin and Bruno Tertrais argue that the two trends are not incompatible. They believe that freedom of movement supposes that borders are widely accepted and delimited.

Let’s end with a cheerful story:

O

O

The commanding officer Cdr. s.g. Per Starklint of the Danish warship HDMS Triton on Hans Island during August 2003

Unresolved territorial disputes can be peaceful. For decades, the Danes and the Canadians expressed their disagreement about the tracing of the border on tiny Hans Island by planting national flags and leaving behind a bottle of whisky or brandy. In 2022, the two nations finally agreed on a plan to divide the island.

More book spreads: