Some 100 years ago, Russian biophysicist Alexander Chizhevsky published a study arguing that the main socio-political events in history followed the 11-year solar cycle (also known as the sunspot cycle.) Tracing dozens of historical events, Chizhevsky asserted that periods of high sunspot activity lead to increased mass “excitation” and brought about war, riots and revolutions. In contrast, periods of low solar activity correspond to periods of relative peace and creativity.

Agnieszka Polska, The New Sun, 2017

Zhiyuan Yang, Make A Little Sun, 2024

Chizhevsky’s theory is one of the main inspirations behind the essayistic group exhibition Genossin Sonne (Comrade Sun) at HMKV in Dortmund. Dedicated to artistic works and theories that explore the connections between the sun and socio-political movements, the show explores questions such as: “To what extent does not just the sun but also the cosmos play a part in historical processes?” and “Is there, as Chizhevsky and the Soviet cosmists claimed, a connection between solar storms and terrestrial revolutions?”

Comrade Sun at the Dortmund U. Biophysicist Alexander Chizhevsky’s timeline shows the connection between solar storms and revolutions. Photo: City of Dortmund / Silke Hempel

A massive graph on the wall, based on a diagram from Shifting Pattern of Extraordinary Economic and Social Events in Relation to the Solar Cycle, a paper published in 2020 by IMF economist Mikhail Gorbanev, seems to confirm Chizhevky’s theory of a correlation between solar activity and major revolutionary events. Some revolutions that align with sunspot activity stand out clearly, such as the French Revolution or the fall of Communism in 1989–9. Others, however, are absent. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) isn’t there. Neither are the revolts that were suppressed. Nor the upheavals our Western-centric perspective never took into consideration.

Whether you are seduced by Chizhevsky’s theory on the parallels between solar activity and mass human behaviour or not, it’s hard to ignore the crucial impact of the sun on all aspects of our lives. The massive star functions on the one hand as a source of life and energy for political struggles and on the other as a warning figure whose sheer mass and lifespan underline the brevity of human life (and humanity as a whole) on planet Earth.

Here are a few of the works that i discovered in the exhibition:

Anton Vidokle, The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun, 2015, video, © Anton Vidokle

Anton Vidokle, The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun, 2015, video, © Anton Vidokle

Anton Vidokle, The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun, 2015

Anton Vidokle, The Communist Revolution Was Caused by the Sun, 2015. Film still. Photo: Ayman Nahle

The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun, the second part of a film trilogy by Anton Vidokle, probes Cosmism’s influence on the twentieth century and suggests its enduring relevance. The cultural and philosophical movement known as Russian Cosmism has been somewhat forgotten. Characterised by a deep faith in technology, immortality and outer space colonisation, its utopian vision inspired thinkers, architects and artists of late 19th- to early 20th-century Russia.

The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun explores the links between cosmology and politics through the figure of Tchijevsky. Filmed in Kazakhstan, the work describes Chizhevsky’s research on the influence of solar emissions on human society, psychology, politics and economics. Kazakhstan, where Stalin sent Chizhevsky to undergo eight years of Soviet “rehabilitation”, has also been the heart of the Soviet, and now Russian, space programmes. It’s from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, for example, that Russian crewed flights are launched into space.

Many scenes in the film are full of contrasts: some people are still getting around on horse, a woman and a horse stand underneath a massive chandelier that had been engineered to keep cosmonauts healthy in space but was given to government officials “to prevent them from going senile.” Vidokle also collages excerpts from Chizhevsky’s writing with stories about body preservation and considerations regarding the source of all life and nourishment on Earth: the sun. The Communist Revolution was Caused by the Sun concludes that a human being ‘is not only an earthly being, but also a cosmic one.’

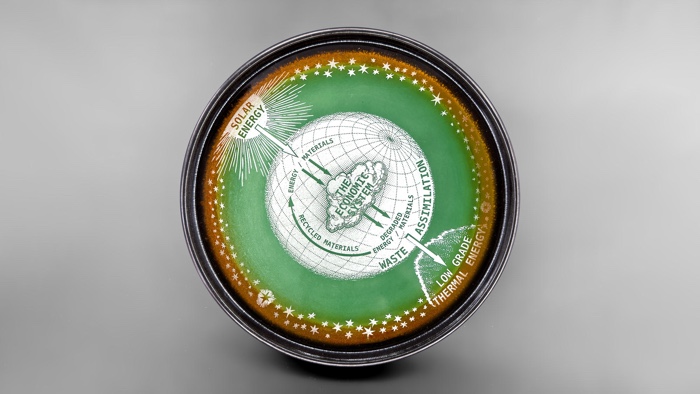

DISNOVATION.ORG, Eating the Sun, 2024

DISNOVATION.ORG, Eating the Sun, 2024

DISNOVATION.ORG, Eating the Sun, 2024

DISNOVATION.ORG, Eating the Sun, 2024

Looking at the sun as an energy supplier for life on earth, DISNOVATION engraved a set of ceramic dinner plates with images and texts that articulate a political economy of strong sustainability centred around the Sun.

Starting from the premise that the Earth‘s geological resources are finite, Eating the Sun details how photosynthetic organisms convert solar energy into organic matter, generating the carbon compounds that form the basis of life on Earth, from fishing to agriculture, cooking to building. This investigation illustrates how economic mechanisms based on renewable solar energy could inform governance to achieve lighter ecological footprints and sustainable human coexistence within ecosystems.

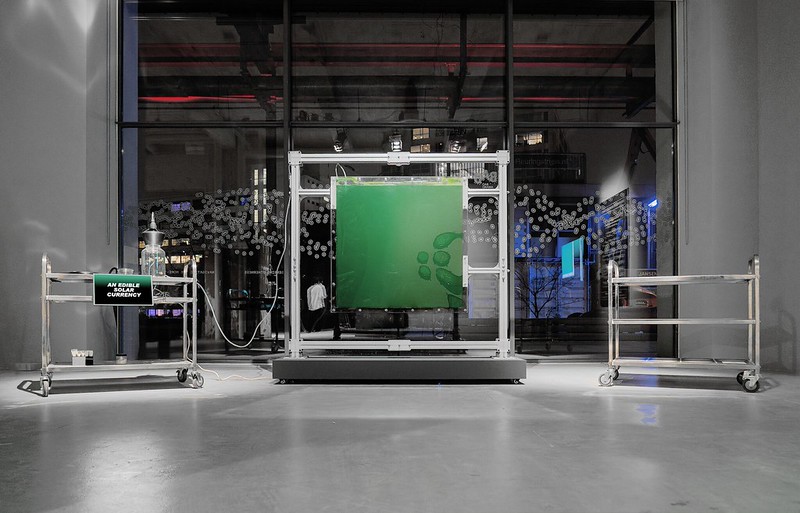

DISNOVATION.ORG, The Solar Share, 2024

The Solar Share, another work by DISNOVATION, exposes how daylight can be the basis of the food chain. The installation consists of a culture of spirulina microalgae inside a one-square-metre bioreactor placed in front of a window. Through photosynthesis, the microalgae produces edible biomass, becoming a “Solar Share”, a new economic unit corresponding to the average daily biomass yield on one square metre of the Earth’s surface. Sunlight is literally transformed into value that can be consumed, exchanged or stored as a currency.

The Solar Share project challenges prevailing economic models by highlighting human dependence on photosynthesis and proposes phytobiomass (here as edible microalgae) as a new economic unit. The experiment raises the question: what would an economy based on photosynthesis look like?

Ho Rui An, Solar: A Meltdown, 2014–2017, lecture and video installation with digital print, solar-powered toy and punka (colonial fan). Photo Ho Rui An

Ho Rui An, Solar: A Meltdown, 2014–2017, lecture and video installation with digital print, solar-powered toy and punka (colonial fan). Photo Ho Rui An

Ho Rui An, Solar: A Meltdown, 2014–2017

The idea for Solar: A Meltdown emerged when Ho Rui An saw a wax figure of Charles Le Roux in Amsterdam‘s Tropenmuseum. Le Roux was a Dutch anthropologist working in India at a time when the Netherlands controlled a part of it, and to Ho Rui An’s great surprise, the statue had traces of sweat on its back. It is from this image of ‘colonial sweat’ that the artist investigates how the merciless sun of colonised countries was beating down on European colonialist bodies and how the images we have of the colonialists clad in pristine white outfits are completely unrealistic. The installation features a solar-powered Queen Elisabeth toy, a print of the sweaty wax figure, a punka colonial fan and a video documenting a performance lecture. Each in their own way, these elements symbolise the colonial project and its attempts to resist the tropical sun.

In the lecture, Ho Rui An attempts to recover the image of colonial sweat, to rewrite the tropes and images that are still circulating about colonial bodies. Using excerpts from films, archive photos as well as contemporary images, the artist appropriates the format of colonial lectures of anthropologists who travelled to the colonies to collect images that they brought back to the European cities in the form of lively narratives full of exotic and astonishing facts and photos that would enthral audiences.

The work also resonates with the contemporary, with this moment of global meltdown where our own sweaty backs remind us of the power of the sun.

Gwenola Wagon, Chronicles of the Dark Sun, 2023

Gwenola Wagon’s Chronicles of the Dark Sun is a dystopian tale set in a not-so-distant future when humans who have survived climate collapse and war are forced to shelter from the rays of the sun. Condemned to live in darkness, they are fascinated by this star whose warmth and light they cannot experience directly anymore.

The humans then train an AI on the precise but subjective memories of a woman who remembers what daylight was like. The result becomes humanity’s image of its collective past.

Wagon’s film essay recycles photographs from personal albums, advertising shots and scientific images found in the archives of the Solar Observatory in Meudon founded in 1876 by Jules Janssen, an astronomer who invented his own cameras to be able to produce groundbreaking photographs of the sun.

Over the course of the Chronicles of the Dark Sun film, the images, manipulated to varying degrees by algorithms, become increasingly bonkers. They question our unsustainable way to inhabit the planet as well as the way AI has started to shape our relationship to information, science and archives. The artist is particularly interested in what she calls “anarchives“, the algorithmic alternatives to photographic archives.

Sonia Leimer, Space Junk, 2020–24. Exhibition view, Genossin Sonne (Comerade Sun). Photo: Jannis Wiebusch

Sonia Leimer’s Space Junk sculptures make more tangible our deeply flawed relationship to outer space, a driver of innovation but also a vast landfill filled with pieces of disused satellites, parts from spaceships and other man-made debris (such as bits from future AI data centres?)

The space debris that the artist has reproduced look like damaged metal spheres that have just fallen onto the Earth surface. Usually absent from our daily reality, these fragments of infrastructure remind us of the unsustainability of human techno-driven ambitions.

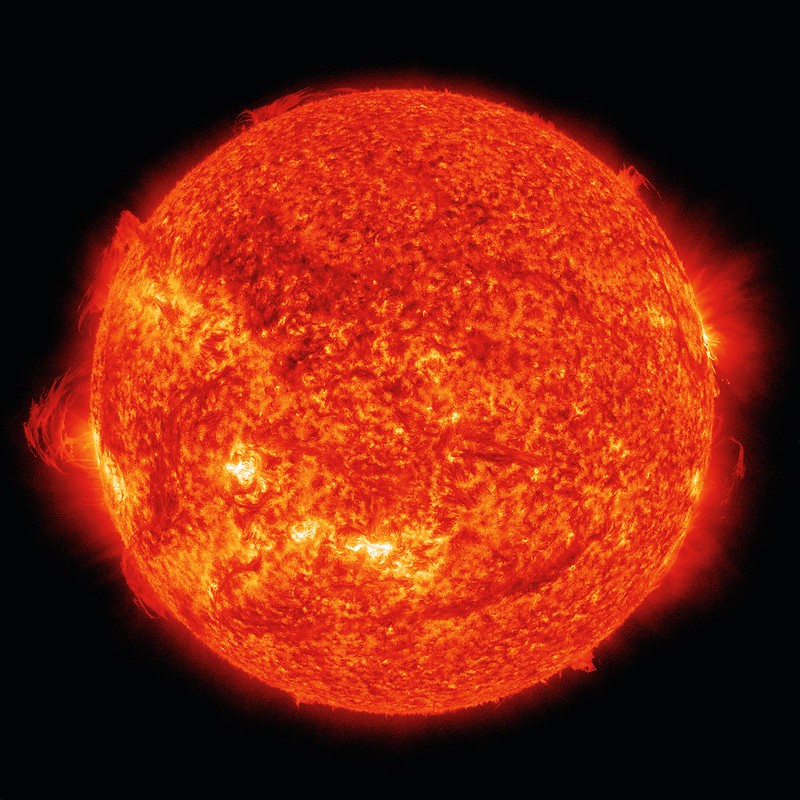

Katharina Sieverding, Die Sonne um Mitternacht schauen, red, 2011–2014

For “Looking at the Sun at Midnight,” Katharina Sieverding collaged 200,000 high-resolution NASA satellite images into a video loop. The result is a blazing orb that seems to pulsate and expand in 3 dimensions.

The work reveals what the naked human eye cannot normally see: the surface of the sun. At most latitudes (except at the north of the Arctic Circle and south of the Antarctic Circle during the height of summer in these regions), the sun cannot be ‘seen’ at midnight. Its many nuances of yellow, orange and red, the drama of dusk or dawn are not its own, but effects of the scattering of sunlight by our atmosphere. The real colour of the sun is white, as it emits all colours of the visible light spectrum at once. One of the most depicted celestial body in the solar system shuns representation.

More images from Genossin Sonne (Comrade Sun):

The Atlas Group, I only wish that I could weep, 2002

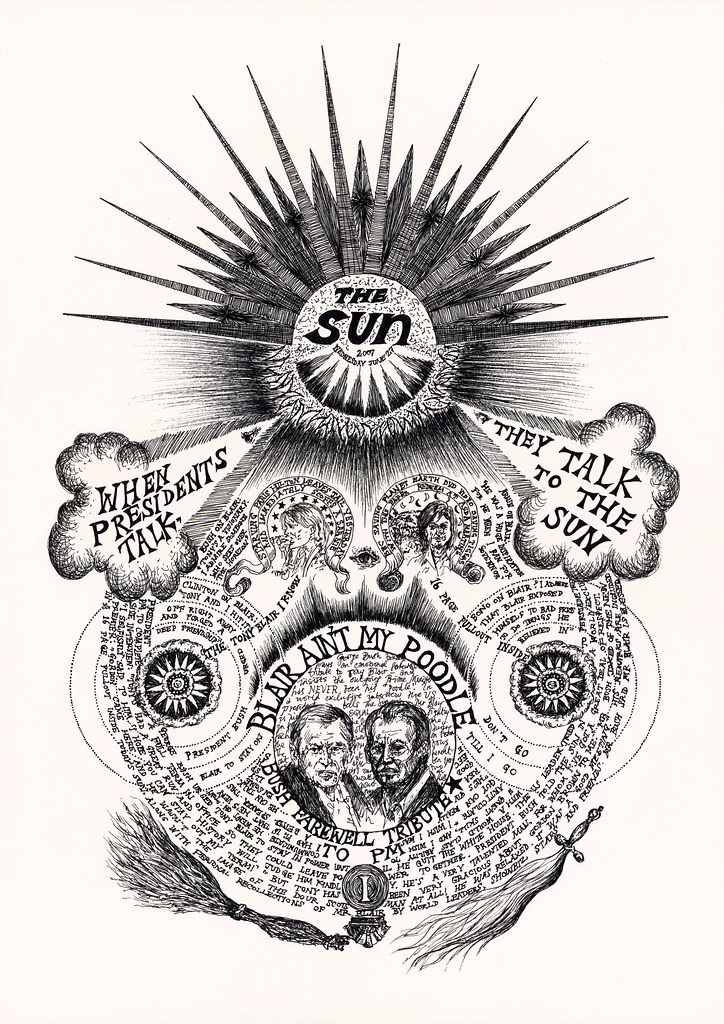

Suzanne Treister, ALCHEMY: The Sun, 27th June, 2007

Exhibition view, Genossin Sonne (Comerade Sun). Photo: Jannis Wiebusch.

Exhibition view, Genossin Sonne (Comerade Sun). Photo: Jannis Wiebusch.

Exhibition view, Genossin Sonne (Comerade Sun). Photo: Jannis Wiebusch.

Agnieszka Polska, The New Sun, 2017

Genossin Sonne (Comrade Sun) remains open until 18 January 2026 at the HMKV Hartware MedienKunstVerein at Dortmunder U, Level 3 & Level 6 in Dortmund. The exhibition was realised cooperation with the Kunsthalle Wien and the Wiener Festwochen | Freie Republik Wien.