What remains after you’re gone? For most of us, the answer to the question translates into money and material goods that might be passed on to friends and family. Ask that same question to an artist and their reaction might be a bit more complex. It’s not so much about heirs, it’s about posterity. Will their legacy be wiped out by the caprices of the art market? Will museum collections continue to be interested in their work? How will their work remain relevant to society when the world is changing so fast?

Mohamed Bourouissa, Network, 2021

My Last Will, an exhibition currently on show at Casino Luxembourg, asked 32 artists and artist groups to contemplate “their legacy and try, each in their own way, to capture the core of what makes up their goals and interests with a central statement or a paradigmatic work. In doing so, they question their presumed significance for a future they will no longer experience and whose measures of value are still completely unknown to them.”

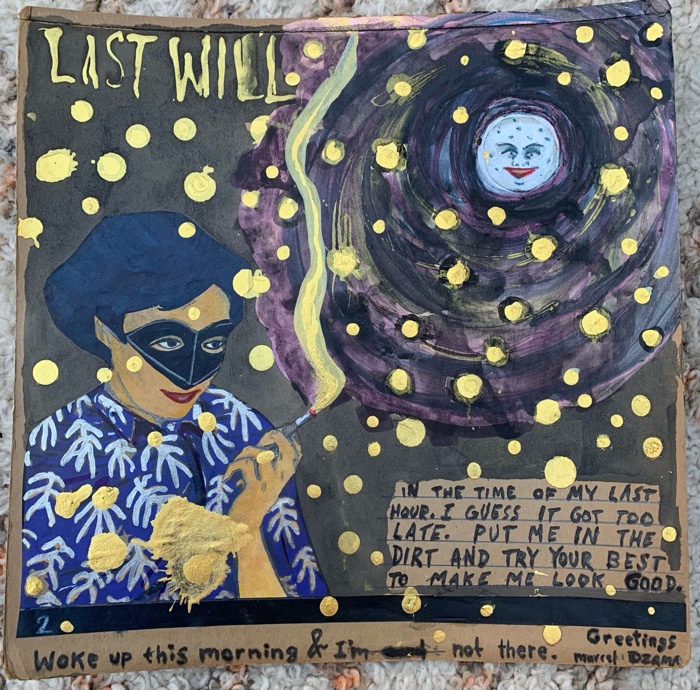

Marcel Dzama, Last Will, 2023

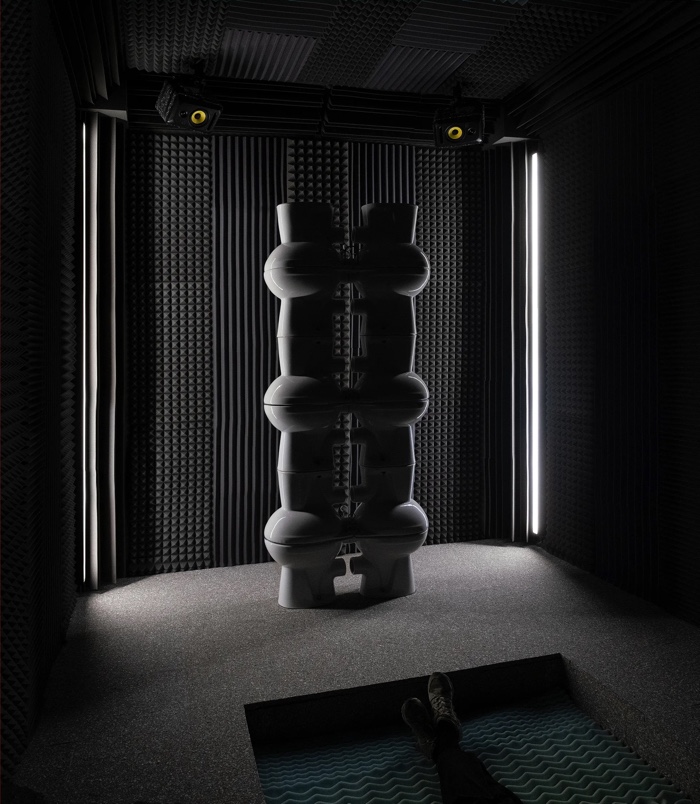

John Bock, Special Asst. to Asst. Director in Charge of Info, 2022. Installation view, Casino Luxembourg. Photo: Jessica Theis

Instigated by the artist duo M+M (Marc Weis/Martin De Mattia), the project started with an artists’ book (with the kind of Japanese binding i always found very satisfying) that collects texts, collages and image contributions from the participating artists. Five works were also commissioned for the exhibition.

Some of the artists used the brief to ponder the realities of death, whether their own or that of someone they love. Others critically question the meaning of their creative practice in a future that might be governed by values that are radically different from the ones we adhere to today. Others used the project to express their hope of a world that has shed the last remains of colonialism and extractivist practices. A few of them realise that it would be absurd to pretend that they have any control over their legacy.

Santiago Sierra, Death Counter, 2009/2023. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Laurent Sturm

The entrance to the show is dark and gloomy. Santiago Sierra’s Death Counter displays statistics on worldwide fatalities over the course of the exhibition. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Israel’s massacre of Palestinian civilians in Gaza and the West Bank, the civil war in Sudan, victims of global heating…. The LED information board reminds visitors that art will always feed on the cruellest aspects of human life. There’s also something cynical in the way that the Death Counter reduces the deceased to numbers.

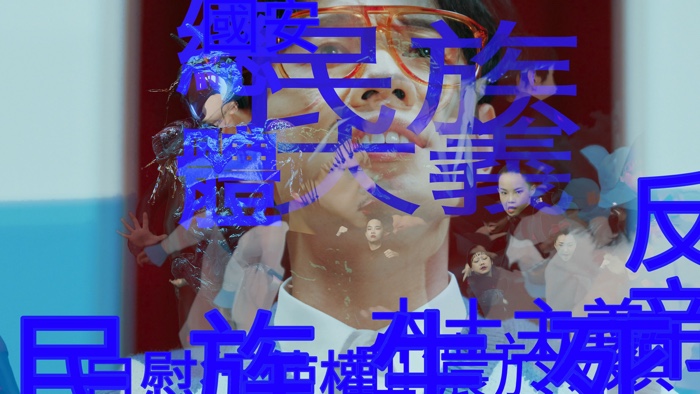

Su Hui-Yu, The Space Warriors and the Digigrave, 2023

Su Hui-Yu, The Space Warriors and the Digigrave, 2023

Su Hui-Yu, The Space Warriors and the Digigrave, 2023

Su Hui-Yu, The Space Warriors and the Digigrave, 2023

Su Hui-Yu, The Space Warriors and the Digigrave, 2023

In East Asia, in the 1980s, during the final years of martial law in Taiwan, one of the island’s three official TV stations produced a weird and now rather obscure sci-fi series called Space Warriors. It was copied from the Japanese series Super Sentai with added local elements. What made the series stand out was its subtle championing of nationalism, Confucianism, patriarchy and other values.

Su Hui-Yu‘s flamboyant video The Space Warriors and the Digigrave investigates his country’s history from a future perspective by mixing together utopia, the values that the TV show advocated and the post-colonial history of Taiwan and East Asia.

The Digigrave is a spaceship inspired by the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall erected in Taipei in memory of Chiang Kai-shek, a former President of the Republic of China. The digital gravestone hovers above a mix of fiction and history, made of battles, alien invasions, coastal landscapes and a society looking for new meanings. The video installation is bold, glorious and troubling. The undercurrent of threat calls up China’s imperialistic plans for the island.

My Last Will. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Jessica Theis

My Last Will. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Jessica Theis

Upstairs, the atmosphere changes drastically: light floods the rooms and the floors are covered with a joyful yellow carpet.

Lara Almarcegui, Mineral Rights Tveitvangen, Oslo, 2015 (ongoing)

Lara Almarcegui, Mineral Rights Tveitvangen, Oslo, 2015 (ongoing)

In 2015, Lara Almarcegui obtained the mineral rights to an iron deposit in Tveitvangen, near Oslo. The rights extend over an area of one square kilometre, and reach from the subsoil down to the centre of the earth. One of the main objectives of the project is to prevent mining companies from exploiting the land and what lies beneath it. The work also brings to light questions that remain under the radar even today: Who owns the sub-surface of the earth? Who has the right to extract its resources? How is it partitioned and instrumentalised by private interests?

Almarcegui later got the rights to iron deposits in other countries, such as Austria. Mineral Rights are regulated differently from country to country and it is extremely difficult for a private individual to acquire them. Even though she worked with local geologists to secure mineral rights, the artist was often refused the option of purchasing them.

“The works I have been doing about holding mineral rights are a success in terms of legacy, because they are preserving material that was formed millions of years ago,” she wrote. “These works are a failure because mineral rights for exploration cannot be held in perpetuity.”

Renzo Martens, White Cube (trailer), 2020

Renzo Martens, White Cube, 2020. Photo: Human Activities

Renzo Martens’ documentary White Cube attempts to demonstrate how former colonies can use the art market system for their own benefit. The Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC), a plantation workers’ cooperative based on a former Unilever plantation in Lusanga, DRC, was formed in 2014 together with biologist and environmental activist René Ngongo.

CATPC members make clay sculptures that evoke the exploitation of labour and trade relations. The sculptures are 3D scanned and then reproduced in cocoa and palm oil in Amsterdam, the world’s largest cocoa port, before being exhibited and sold in art galleries and museums worldwide. With the income generated from the sales of their art, the workers are able to buy back the land that had been confiscated and taken from them by Unilever. The land reclaimed is then turned back into diverse, ecological and community-owned cocoa and palm oil gardens: the post-plantation, a sustainable antagonist of exploitative colonial practices characterised by ruthless labour conditions, monocultures and environmental ravages.

In 2017, CATPC built an art centre named White Cube in Lusanga, a village that was once at the heart of an empire of palm oil that relied on the destruction of forests and the enslavement of entire communities. When the exploitation of the land was no longer profitable, Unilever sold it off. By turning a container of art, the white cube, into the content itself, WCL exposes the white cube to critical discourses and shows the fallacy of the claim that a white room makes exhibition as neutral and “contextless” as possible.

By placing a white cube on a plantation, a site that has funded many art institutions in the Western world (for example, the Tate Modern “Unilever Art Series”), CATPC and Human Activities claim to “prove that artistic critique on economic inequality can effectively reverse that inequality”. Furthermore, plantations and colonial trade in general have historically supported the establishment of cultural institutions in the Western world.

Perhaps Renzo Mertans’ legacy is the most rearding he could hope for. He has been championing CATPC’s work for years. Now the collective no longer needs his white man gravitas and fame to get the respect of the international art world.

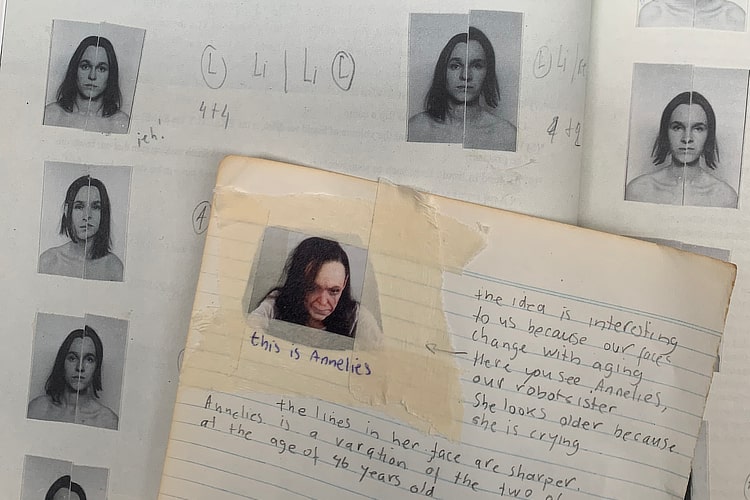

L.A. Raeven, Annelies, 2018. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Jessica Theis

L.A. Raeven. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Jessica Theis

An exhibition looking at death and legacy was always going to feature artworks that make some people feel uncomfortable. Two of them made me uneasy. The first one is the animatronic of a deeply depressed woman. Called Annelies, it looks like a tormented version of twin sisters who have been closely collaborating their entire lives under the artistic name of L.A. Raeven. It sits on the floor, barefoot and dishevelled, lamenting the hypothetical death of whichever twin dies first. Like a physical version of grief tech, the robot might one day provide solace to the twin who’s left behind.

The robot reacts as you approach, which is nothing to write home about, except that it moves in a creepy way. I do like the issues Annelies raises though: What would it be like if you had the ability to copy yourself or your loved one? Would the copy better help someone deal with the fear of being left behind?

MASBEDO, Madri, 2023

The second artwork I found difficult to look at is Madri. Nicolò Massazza and Iacopo Bedogni from MASBEDO shot slow, extreme close-ups of their elderly mothers. The camera lens details the women’s wrinkled hands, arms and faces. I found it tender but also intrusive. The women do not seem to care. What you see is the film being projected onto the screen of an empty old cinema. MASBEDO created a lasting memory of women they love and whom they are afraid to lose.

Clemens von Wedemeyer, Against Death, 2023 (2009). Photo: Sheila Burnet

My Last Will. Installation view at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, 2024. Photo: Jessica Theis

In the film Against Death, an explorer tells his anthropologist friend that, following a ritual performed by an indigenous community in Latin America, he has been cursed with immortality. His friend refuses to believe him. The explorer then grabs a knife, slits his own throat in front of his friend and falls on a Persian carpet just like the one in the exhibition. Life soon returns to his body, he stands up, and the story is repeated in a seamless loop.

By using a loop, Clemens von Wedemeyer draws parallels between a film that repeats itself ad-infinitum and immortality that traps the body in a loop that defies time and physics. The loop, along with the carpet, also blurs the boundaries between the fiction of the narrative and the physical reality of the viewer.

More images from the exhibition:

Clément Cogitore, Zodiac, 2007

PPKK (Sarah Ancelle Schönfeld & Louis-Philippe Scoufaras), 2024. Installation view, Casino Luxembourg, 2024

My Last Will was curated by artist duo M+M (Marc Weis/Martin De Mattia). The show remains open at Casino Luxembourg until 08 September 2024.