What Design Can’t Do. Essays on Design and Disillusion, by writer, artist and designer Silvio Lorusso. Published by Set Margins.

Graphic design: Federico Antonini.

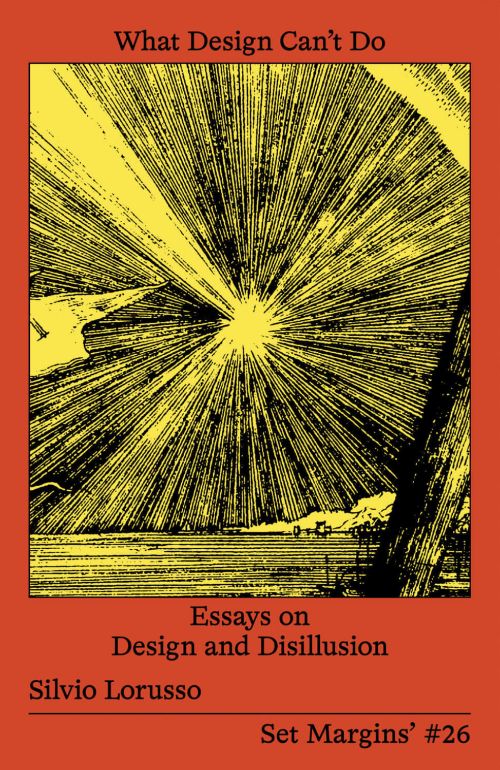

Do you remember when design vowed to make sense of “complexity”, vanquish all the world’s ailments and add layers of “seamless” enchantment to our existence? When design was a positive force of change? Those promises might still be there today, but our collective faith in the power of ‘creative destruction’ and boundless innovation has dwindled.

Do you remember when design vowed to make sense of “complexity”, vanquish all the world’s ailments and add layers of “seamless” enchantment to our existence? When design was a positive force of change? Those promises might still be there today, but our collective faith in the power of ‘creative destruction’ and boundless innovation has dwindled.

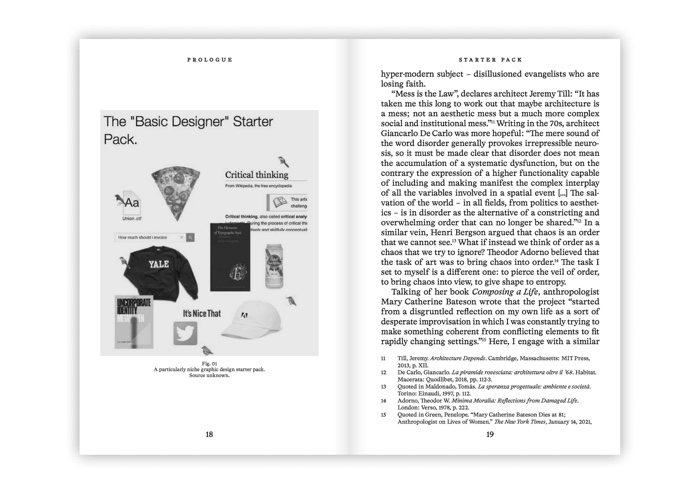

In his book, artist and designer Silvio Lorusso investigates the reasons behind the sense of disappointment that pervades design, disentangling the messy daily reality of the profession from the excessive positivity of its discourse.

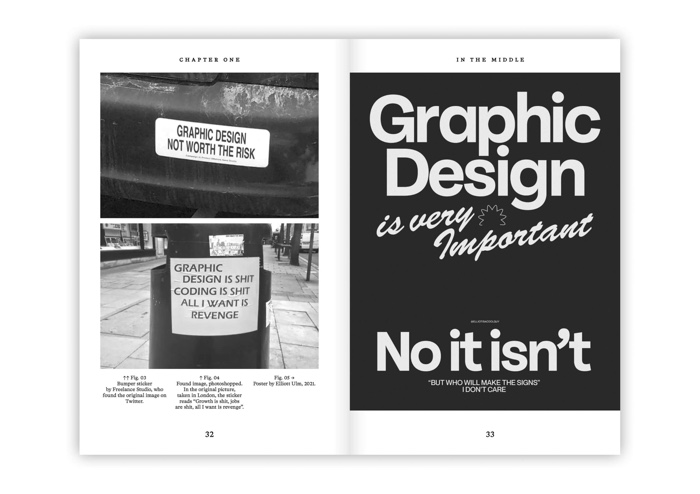

The chaos, it seems, cannot be contained; logo generators and other digital tools that automatise design processes, repetitive tasks, online job platforms for creative freelancers that atomise design gestures, low financial rewards -especially if you consider the decreasing return on investment from higher education, feeling of being unable to shape the workings of the profession, etc. Worst of all, the uneasy position that designers occupy within consumerist enterprises leaves them very little room to deploy any ethical ambitions they might have.

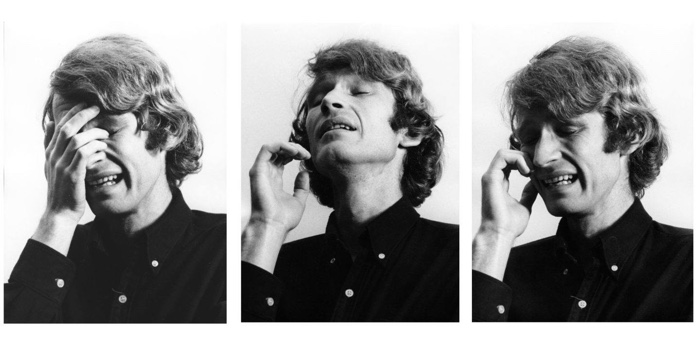

Bas Jan Ader, I’m too sad to tell you, 1970 – 1971

Fiverr’s Marketing Campaign getting the feedback it deserves in the subway. Photo: hackernoon

What Design Can’t Do looks at how design is pushing back against this crisis of legitimacy. Some of the strategies the book analyses will sound familiar to many of us: the injunction to ‘learn to code’, the manifesto craze, the workshopisation of the discipline, the appropriation of countercultures, etc. And the rise of design movements that, instead of changing the world through products and services, claim to shape debates and influence public opinion. None of that has quite managed to give designers the authoritativeness they aspire to.

Lorusso’s critique is sometimes brutal, but it never turns angry. He seems to genuinely care for the design discipline(s.) His book is honest and impeccably researched, calling upon the words of philosophers, design theorists, design historians and other thinkers to show how designers keep trying to reinvent themselves as self-anointed political activists, intellectuals of techniques (instead of technical intellectuals), slayers of capitalism, etc. And i’m going to add “artists” to the list. I can’t count the number of times i’ve heard designers tell me that they are also artists. In a few cases, it made perfect sense. In most cases, not so much.

The book is a call for a serious admission, examination and “organisation” of the hopelessness that torments design. Before trying to solve the world’s many problems, design needs to confront its own troubles.