Cultural space are slowly reopening to the public here in Italy and I’m taking advantage of the very very quiet touristic season to drag my collection of face masks around art cities. First stop: Rome for the unexpected joy of visiting the Vatican museums without the need to queue and a discovery of the exhibition REAL_ITALY at MAXXI, the national centre for the contemporary art and architecture.

Danilo Correale, Diranno che li ho uccisi io / They Will Say i Killed Them (video still), 2017-18

REAL_ITALY presents the winning works of a competition held in 2017 by the MiBACT Italian Council General Direction for Contemporary Creativity. The result is a brutally honest display of social exclusion in suburbs, prisons and refugee camps, colonialist heritage, censorship, public spending scandals and fight against underworld crimes.

The works draw a uncompromising, haunting and somewhat melancholy portrait of Italy as it is today. It is dark but never hopeless. The exhibition demonstrates that in spite of all its shortcomings, the country still manages to nurture lucid, sensible and talented artists.

Here’s some of my favourite works in the show:

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18

. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Alterazioni video, Incompiuto: La nascita dello stile/Unfinished: The Birth of a Style, 2017-18

. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

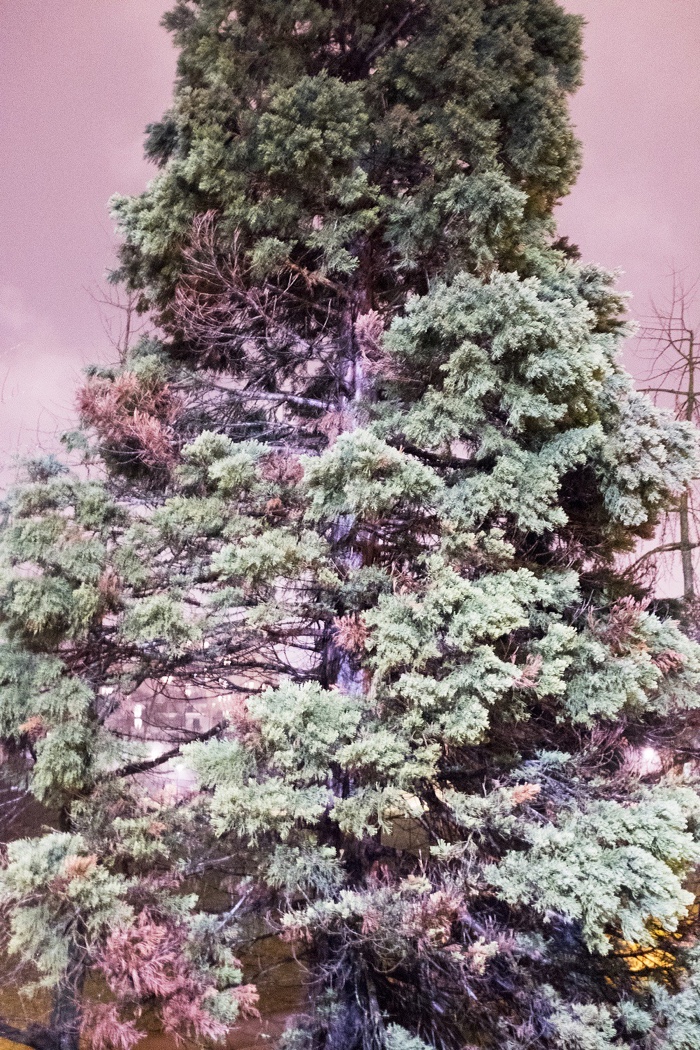

Half of a viaduct, a swimming pool with weeds growing between the tiles, rows of pillars that do not support any road nor bridge, walls in the middle of nowhere, etc. So much concrete poured, so many unfinished structures decaying in otherwise stunning landscapes.

Over the past 10 years, Alterazioni Video has crisscrossed Italy to document, map and reflect upon unfinished public works in Italy. Having collected over 750 works on the whole Italian territory (including 350 in Sicily), they’ve declared that the phenomenon is so widespread and had such an impact on the appearance of the Italian landscape that it constitutes the most important Italian architectural style of the last 50 years. They call it the Incompiuto (the Unfinished.)

The series both denounces and celebrates this strangely appealing mix of ruin porn and Mediterranean scenery. Under their critical eye, these symbols of waste of public resources and environmental crimes are turned into savage monuments, crude markers in the landscape.

Yuri Ancarani, San Vittore (video still), 2018

Yuri Ancarani, San Vittore (video still), 2018

Yuri Ancarani, San Vittore (video still), 2018

When children visit their parents at the San Vittore prison in Milan, they’re subjected to a thorough security check. Their bags are searched, their shoes and toys are checked, they have to go through a metal detector, a security guard pats them down. They are then lead by the hand along long corridors to the visiting room where their father awaits. No matter how gentle the guard, the violence of the procedure is upsetting.

Yuri Ancarani not only filmed the arrival of a child inside the San Vittore prison in Milan, he also shows drawings made by children of inmates during workshops run by an NGO which mission is to protect the rights of prisoners and their families. There are drawings of prison bars, bloodied dolls, figures of authority and many castles. The prison is like a formidable fortress to them.

The way the artist conjures up the prison regime through the eyes of children is poignant and hypnotising.

While doing some research to write this review, I realised that Yuri Ancarani was the artist behind one of my favourite video artworks. Il Capo (The Chief) was shot in a marble quarry in the Apuan Alps as Il Capo guides his men through the extraction process. I didn’t write down the name of the artist at the time and couldn’t find any trace of the video again. I’m glad I’ve finally found him/it.

Eva Frappicini, Il pensiero che non diventa azione avvelena l’anima/Words Without Action Poison the Soul, 2017

Eva Frappicini, Il pensiero che non diventa azione avvelena l’anima/Words Without Action Poison the Soul, 2017 ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

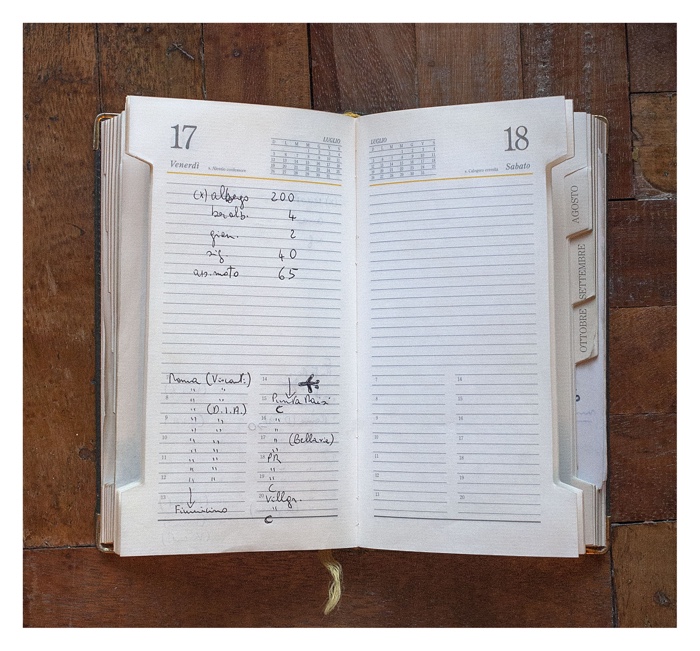

Eva Frappicini, Paolo Borsellino. Personal agenda, 1992. From the project Il pensiero che non diventa azione avvelena l’anima/Words Without Action Poison the Soul, 2017

Eva Frappicini, Paolo Borsellino. Personal agenda, 1992. From the project Il pensiero che non diventa azione avvelena l’anima/Words Without Action Poison the Soul, 2017

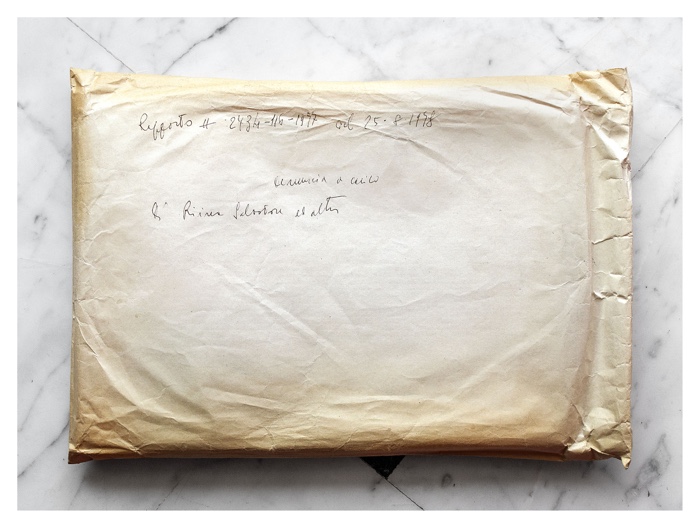

Eva Frappicini, Rocco Chinnici. Folder containing Report dated 25.08.1978 on Riina Salvatore and others. From the project Il pensiero che non diventa azione avvelena l’anima/Words Without Action Poison the Soul, 2017

Words Without Action Poison the Soul is an ongoing research that documents in photos the everyday “tools” used by magistrates, journalists, trade unionists, police inspectors and private citizens who fought the mafia from the 1970s to the 90s. Some of them are famous: Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino, Libero Grassi, Boris Giuliano, etc. Others were equally brave but their name has travelled far less.

Eva Frappicini hunted for manuscripts of the speeches, sketches, notebooks, agendas and other notes that belonged to these courageous men and women. She photographed the objects front and back and in 1:1 scale which gives an intimate feel to their work. This sense of having a private encounter with the documents is reinforced by the way the photos are exhibited. The public can navigate the photos through a searchable structure, with vertical drawers that you can pull out as individual photographic racks.

Over the course of her research, the artist found out that this precious historical documentation, these very objects that bear witness to the fight against the mafia are not archived in an organised and systematised way. Some are kept in archives but stuffed randomly inside big paper envelopes. Others remain in the hands of families who are not sure what they ought to do with them. What will happen to these documents in the future? Don’t these traces left by people who took a stand against the Sicilian Mafia deserve to be preserved and shared with greater care?

Margherita Moscardini, Inventory. The Fountains of Za’atari, 2017. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Margherita Moscardini, Inventory. The Fountains of Za’atari (video still), 2018

Margherita Moscardini, Inventory. The Fountains of Za’atari, 2017. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Opened in 2012 to welcome Syrians fleeing the civil war and located in a semi-desert area of Jordan, Camp Za’atari is one of the largest refugee camps in the world.

Margherita Moscardini mapped all the fountains built by the residents in camp courtyards. She then produced a catalogue of the fountains, with the name of their author, the materials used, the year they were made, etc.

The artist went further. She suggests that the fountains could be copied and adopted in cities across Europe, as sculptures for public space. An official system of acquisitions would enable the designer of the fountain to benefit directly from the sale, thereby creating a system that supports the camp’s economy.

In Moscardini’s scheme, the sculptures would also receive special jurisdiction that includes elements of extraterritoriality, turning them into spaces where the law does not apply. Like offices of the United Nations, embassies, the high seas or even the outer space.

Inventory not only highlights the role that cities can play when national states fall short, it also point to the need to rethink refugee camps as urban areas destined to last, and even as models that could potentially be exported.

Leone Contini, Il Corno Mancante/The Missing Horn, 2017-18

. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Archivio Fotografico castello Sforzesco. Photo: That’s contemporary

Leone Contini, Il Corno Mancante/The Missing Horn (video still), 2017-18

Leone Contini, Il Corno Mancante/The Missing Horn (video still), 2017-18

Monte Stella is an artificial hill created using the debris from the bombings of Milan during WWII. The ethnographic collections of the Castello Sforzesco were destroyed by the attack. Some works were recovered and moved to the Mudec Museum of Cultures. Many others remain buried in the artificial mountain. Among the works of art recovered and restored is the sculpture of the buddhist deity Yamāntaka (the Death Destroyer). Its left horn, however, is now lost. It is probably still buried somewhere in Monte Stella along with several other fragments from the sculpture. This representation of a divinity is a museum object for most of us but for the Buddhist communities living in Milan, the sculpture is still imbued with spiritual life. The Yamāntaka is one of the many “exotic” artefacts that were removed from their original contexts during the colonialist period, with the promise that Europeans would take “better” care of them. And yet, it became one of the casualties of a war between European powers.

The video and the pile of rubble in the exhibition space evoke Contini’s impossible search for the missing horn in Monte Stella, using the small artificial mountains as an archeological site. Il Corno Mancante/The Missing Horn is part of a series of performances that act as healing gestures and symbolise opportunities to bring together not only fragments of artefacts but also different cultures and memories.

More images from the REAL_ITALY exhibition:

Nicolò Degiorgis, Le Baron Chéper, 2017

Nicolò Degiorgis, Le Baron Chéper, 2017. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Flavio Favelli, Serie Imperiale (Zara e RSI), 2018

. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITALY. ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Anna Franceschini, CARTABURRO (video still), 2017

Anna Franceschini, CARTABURRO, 2017. At MUSEO DEL MAXXI. Opening of the exhibition REAL_ITAL ©Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

REAL_ITALY was curated by Eleonora Farina and Matteo Piccioni. The exhibition remains open at the MAXXI in Rome until 26 July 2020.

Related story: Future farming. How migrants can help Italian cuisine adjust to climate disruptions.