I could try and sum up Tim Shaw‘s practice by saying that it focuses on the relationship between sound, site and technology. But that would be unfair and depressingly unexciting. His musical performances, installations and site-responsive interventions use sound to investigate under-explored aspects of technology and invite the public to experience the surrounding world with a different, more attentive ear.

In 2017, the artist asked the public to send him photos of darkness and recordings of silence. He turned the results of his unusual request into an installation called Radio Television for a festival being held in a dark forest without internet access or phone signal. In a collaboration with Sébastien Piquemal, he played a concert through the audience’s smartphones, using the devices as speakers he controlled live. A few years ago, he transmitted Morse Code into the North Sea and used DIY Hydrophones to pick up the “aqua-augmented” sound.

Tim has presented his performances and installations all over the world, he works as a lecturer in Digital Media at Culture Lab, Newcastle University and has been selected to be one of the 2019 artists of SHAPE, a platform for innovative music and audiovisual art from Europe.

Tim Shaw, Transmit/Receive from Tynemouth (Morse Code being transmitted into the North Sea and DIY Hydrophones picking it back up again), 2015

Tim Shaw, Transmit/Receive, 2015

Hi Tim! Your profile page states “Tim’s practice is concerned with the many ways people listen” but do you feel like people are still listening nowadays? Our culture is very visual. There doesn’t seem to be much dialogue either. Cultural and political experts keep on saying that we’ve even lost the ability to listen to each other. How do you get people to pause, forget about their smartphones and listen?

Well I am as addicted to my smart phone as the next person who owns a smart phone, so I don’t think of myself as any different to anyone else living in our digital culture. I do think we often tune out of the aural world and I am interested in finding ways of attending to it. I am interested in listening as a musical or artistic practice. So in my own work I am making primary decisions through listening. In presentations of my work I try to create a space which encourages listening, through sound walks, performances and installations. I think there are many ways to achieve this. Sound walks can be really effective (I do walks with and without technology) as a way of opening up an awareness to our sonic environments whilst moving through them.

Darkness is another way, if we reduce or play with light in connection to sound it can bring out another way to experience sound.

Tim Shaw, Ring Network

I am very curious about Ring Network. Three bells in a gallery space. When they ring, the sound is recorded on the local computer and then sent to servers in Korea, Iceland and the USA. Once the files reach the remote servers, they are sent back to the exhibition space and played through a speaker at the time it took to travel around the world and back. Is the latency very significant and does it reflect the geographical distance between the exhibition space and the data centres where the servers are located? I always imagined that digital information traveled so fast through optic cables and that sometimes the route they adopt to reach their destination is so reliable that in the end it doesn’t matter where the servers are located.

My understanding of this is very different. I believe there are servers placed in all the buildings around the New York Stock Exchange to speed up server transactions, I believe they call it high frequency trading. When there is that much money involved smaller then milliseconds count. The geographical consequences of network culture is super interesting to me. We sometimes think of the internet as this immaterial thing but its really not, it has a very material consequence, a lot of early net art explores this. In Ring Network the latency is really variable, it is dependant on a whole bunch of different factors; the time of day, the server traffic in the country the server is hosted, how many people are on the gallery Wi-Fi etc.

The time stretching of the recorded bells is noticeably different each time a transaction happens. As listeners we can hear the geospatial consequence of networked communication, which is fascinating to me at least.

You turned the Ring Network installation into a series of performance. How did you adapt it to performances?

Generally I am interested in the ambiguity between installation and performance. I have presented lots of versions of this piece, each time its very different. I usually set the bells ringing and then improvise with the incoming and outgoing sound files. I also try to approach the performance spatially, spreading the bells across the space for sonic complexity. Bells, speakers, sirens, motors, light bulbs and other miscellaneous devices are things I like to use in performances.

Tim Shaw, Ambulation. Various venues worldwide, since 2015

In your interview with Lucia Udvardyova from the SHAPE platform, you mention that recording and communication devices have the ability to change the way we experience the world. Could you give a few examples of that?

Being able to record and broadcast audio changes our sonic world. Listening through microphones, which is something I do a lot, amplifies environmental sound and allows us to perceive it

differently. There are lots of microphones which enable us to extend our ears. Listening devices can let us hear underwater, to electromagnetic energy, to the earth turning, to lighting strikes and meteorites, to insects and animals communicating outside of our hearing spectrum (the list goes on and on). Also with every development in communication technology (or media) a whole new way of experiencing the world emerges. For example with the early gramophone recordings, or radio broadcasts, people would believe they could hear ghosts or the voices of the dead, a common thought was that the record would act as a carrier for spiritual voices from another world.

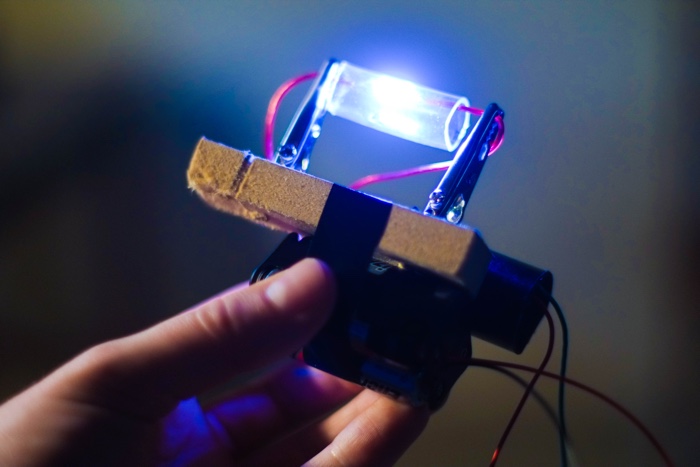

Tim Shaw, “DIY EM pump”. Photo by Sara Lana

You have even worked with esoteric listening devices. Could you tell us about these experiments? Is there anything special or even paranormal about these instruments? In the kind of sound they create or maybe what they pick or the way they are manipulated? Or maybe the way they look?

This is connected to the last answer, listening technologies allow us to hear things we wouldn’t be able to perceive otherwise. Even with a ‘standard’ audio recording, made on your phone for example, you can play the sound over and over again, louder and quieter, boost the background noise, etc. This is also the basis of some esoteric listening practices.

In my own work I started thinking about other ways of listening to the world and started researching early paranormal experiments (it’s easy to go down a rabbit hole on the internet). I built a Raudive receiver, a really simple circuit which basically receives a soft white noise from the world, you can then listen back to it and (maybe) hear voices from the paranormal, the idea is that the noise acts as a shared medium between two different worlds. I have also experimented with electromagnetic pumps which pump electromagnetic energy into a space (I do this quite a lot in performances). What you hear is electromagnetic energy, but it’s interesting to work with space and sound in this way. I don’t actually believe that this equipment enables us to hear ghosts, but I do like to explore how technology extends perceptual possibilities, and I like the ambiguity.

Tim Shaw, Radio Television, 2017

Tim Shaw, Radio Television, 2017

For the 2017 edition of the Sanctuary festival, you asked the public to document darkness, record remoteness and send silence. These sound like 3 mythical creatures. Unobtainable, vanished, romantic. What kind of material did you receive from the public? Could you give us a few examples?

The basic idea around this project was to explore a work which was made up of online contributions from the public, using the provocations you mentioned above. Then presenting them in a space which is completely disconnected from the internet. Just using those simple statements I got a huge variety of different contributions. People could send images, sounds or text, and each of these were appropriated and displayed outdoors on the Sanctuary festival site.

Recordings of silence were very interesting, it’s fascinating how people interpret this term. I had some recordings which were really loud but taken in nature, away from human ’noise’. Others were so quiet you could only hear the recorder, which is also not silence. I guess I was attempting to get people to record things they wouldn’t usually think of, the hope was that this would engage them in acts of attentiveness. It was surprising the variety of results I got.

And how did you translate what you had received into a work called Radio/Television? I’m particularly interested to hear about the kind of natural interference and interruption that distorted the images.

So these messages which were received through an online portal were then retransmitted in the offline space. I used radio to transmit the messages across the festival site using a transmission and reception tower. As radio is inherently noisy there was a lot of signal loss, also, perhaps most interestingly, changes in the environment effected how the pictures turned out. Variations in temperature and humidity created distortions on the images which you could see in real time.

The work starts with silence and darkness and yet you end up calling it Radio/Television, a reference to two now relatively dated media. Is there some sarcasm in that title and the technology you chose?

Haha, maybe subconsciously. Also maybe I have a problem with naming works in general. Radio/Television was really quite a straight forward way of explaining what was happening. I was using radio to transmit images, in radio this is called Slow Scan Television (SSTV).

Tim Shaw, Jarrow Slake, 2019

I was listening to Jarrow Slake today. There’s something very ‘satisfying’, very rich and multidimensional about it. What is happening in the recording? We hear water. Insects? Birds? How did you get so much life and so many layers in one take? What makes the location so special?

Jarrow Slake (the site the track is named after) is close to where I live in the north of England. Its a crazy, post industrial place frequented by fishermen, drug dealers and a field-recordist (me). I am very lucky to be able to travel and listen to environmental sounds all around the world but sometimes the most interesting sounds end up being really close to your house! And Jarrow Slake also has a super interesting history (readers can google that if they like). I went there and by chance dipped some hydrophones (underwater microphones) into the mudbanks of the river that runs through the site. I heard these amazing underwater creatures. I kept going back and the sound changed so much depending on the time of day, the tide (it’s a tidal river) and the other activities happening around the space (boats for example). The recording you hear is a single take using 4 hydrophones placed in the river at dusk, just before the sunset. It was premiered in a multi channel listening space at Fri-Art in Fribourg in Switzerland last year.

Tim Shaw, Murmurate at Mining Institute – Newcastle, UK. Photo by Ben Jeans Houghton

Tim Shaw, with John Richards and Tetsuya Umeda (Dirty Electronics), Sacrificial Floors, 2018

Could you tell us something about your perception and experience of the sound art scene? It sometimes feel to me that music and sound experimentations are a bit marginalised. They have their own festivals while the rest of the art work feels very visual. But that’s just my impression as an outsider, what is yours?

To be honest I don’t really know. I studied music and don’t really know the visual art scene. Also I don’t think I am really part of a sound art scene, or I guess I don’t distinguish scenes in that way. Sound art has always had a contentious relationship to music. I think sound has certainly been a thing in the visual art world for a while now. Sometimes the presentation of sound in visual art can be a little disappointing, it’s a difficult medium to work with and doesn’t conform to the same rules as visual media.

Tim Shaw in the Brazilian rainforest. Photo by Sara Lana

You are currently in the rainforest in Brazil, making new work for the experimental music festival Novas Frequencias in December. Now that sounds exciting! Do you already know what the final work will be like?

Yes. I am currently working in an abandoned casino in the rainforest developing some new performance work. I have decided, in solo performances, to work without field recordings and a laptop and to try to work with the space using sound objects, light and found materials. This is more satisfying for me as a performer at the moment.

The environmental sounds around here are amazing, (an intense frog chorus evening, loud nocturnal insects and hundreds of different birds). It’s a really complex listening environment. I guess I want to reflect that in my performance by building a listening space made with a mixture of materials and devices, some of which I find and make here and others which I bring with me. Also I am trying to approach performance spatially, placing stuff around the space and avoid just performing from behind a table. I will perform it here, in the casino and then at the Modern Art Museum for Novas Frequencias in Rio de Janeiro.

I’m also curious about how it feels to be over there. Each time the rainforest in mentioned in Europe, it’s associated with news related to deforestation, fires, persecutions of indigenous populations, drastic loss of biodiversity, monocultures and i could go on for hours. How is the general mood over there? Do you manage to put the newspaper headlines at the back of your head and just enjoy the experience and your work?

Yes. I had this impression before I came, a lot of people I have met a really politically disenfranchised at the moment but I think that is a common feeling across most of the world right now (especially the UK).

I am working close to a national park near Rio de Janeiro, the fires are not a problem which directly effects this place as it’s pretty mountainous. People here have told me that the rainforest is always burning, both naturally and for industrial agriculture but recently there have been many illegal fires in important places in the rainforest. It is a bad moment for Brazilian politics (that’s my impression) but I am really happy to come here and talk to people

directly, rather then remotely receiving media headlines.

Thank you Tim!