One of the most visually seducing exhibitions i visited this year was All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, Julian Charrière‘s solo at MAMbo, Bologna’s Modern Art Museum.

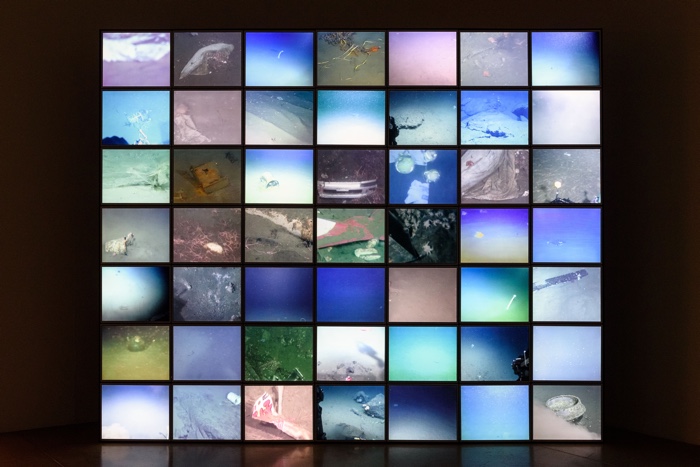

Julian Charrière, Where Waters Meet [3.77 atmospheres], 2019 | © the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Julian Charrière. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Charrière is known for the way he unpeels the various layers of the Anthropocene, revealing the visible, the invisible, the (in)human and the toxic beauty of our world.

“Through a series of videos, photos and installations that cover the story of science, the development of our media culture and the current ecological emergency,” the press material says, “Charrière tries to understand history through his work, looking at the past to imagine what the future holds. Like an archaeologist, the artist gazes into history to understand the future while reflecting on the present.”

Several of the works in the show are set in a microcosm where few human beings venture, a place remote from the rest of the world but which played an important role in human history: the Bikini Atoll. Situated in a far-flung region of the Pacific Ocean, the ‘paradisiac’ coral reef was subjected to some of the most powerful explosions in history—during Operation Crossroads, the U.S. nuclear testing program of the mid-20th century. Since then, the fate of the islands has been largely ignored by everyone. Except by the descendants of atoll’s inhabitants who were forcibly sent into exile.

The artist embarked on an archaeological and geological examination of a landscape that oscillates between our recent past and our distant future. It might be highly toxic to us but it remains magnificent and resilient. And it needs us less than we need it.

Quick walk through some of the artworks on show at the MAMbo:

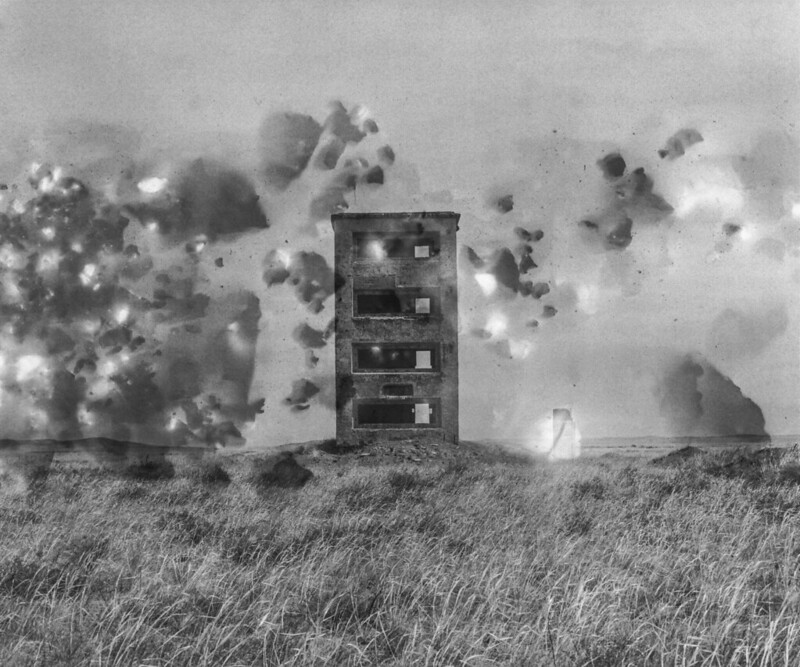

J.W Ballard’s ‘Terminal Beach’ is a short story set on an island that used to be a nuclear testing site. The island is covered with concrete bunkers and other decaying monuments to the nuclear age. That’s pretty much the scenery that Julian Charrière encountered in the Bikini Atoll (Marshall Islands).

Julian Charrière, Iroojrilik (film still), 2016 © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany. Courtesy of the artist

Julian Charrière, Iroojrilik (film still), 2016 © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany. Courtesy of the artist

Julian Charrière, Iroojrilik (film still), 2016 © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany. Courtesy of the artist

The video Iroojrilik follows the diving excursions Charrière made there together with Nadim Samman.

Charrière’s submarine shootings are interrupted by twilight-dawn images of surface. While these sequences are showing a seemingly untouched paradise, the submarine images are inhabited by shipwrecks corroding on the seabed. They were brought in the area in the 1940s and 1950s when the US-military decided to observe the kind of damages nuclear tests would make on old ships.

The film presents a landscape of friction where dreamy subaquatic views and white sandy beaches cohabit with rotting a submerged Ghost Fleet and radioactive plants.

Iroojrilik shows the aftermath of destruction and the recovery of ecosystems devoid of any human presence. Nature seems to brazenly regain control over the scene. Under the water seaweed is covering the shipwrecks. On the shore, abandoned bunkers are colonized by vegetation. Yet, radioactivity is everywhere, invisible and contaminating the environment for millions of years to come.

Julian Charrière, As We Used To Float, 2018

Julian Charrière, As We Used To Float, 2018

Julian Charrière, As We Used To Float, 2018. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

The video installation As We Used to Float, projected on a huge vertical screen, similarly explores Bikini as a space of fantasy and trauma.

Both Iroojrilik and As We Used to Float are sea-stories for the Anthropocene, portraits of a postcolonial geography we engineered at our own peril.

“The atoll became a place that seems a speculative apparition of the future,” the artist told BerlinArtLink. “You can look at something that no one is looking at anymore because it doesn’t exist, but is still being discussed. In 70 years, nobody has been there, it’s very luxurious. We have the oppressive feeling of the radioactivity and history, which is dark and heavy on our shoulders. Then, we have the magnificent pristine coral reefs or the coconut groves that are re-growing. You always have the sensation of looking into a speculative future. It’s a place that is bound with the past, bound with the future and actually very present in an encapsulated reality. So, while you are there, you can describe yourself as a future speculative archaeologist.”

Julian Charrière. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Julian Charrière. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

The main exhibition room was set to make visitors feels as if they were submerged under the water too. Somewhere in the Bikini Atoll. A huge diving bell is hanging in the middle of the room, counterbalanced by plastic bags filled with seawater from the Pacific.

Julian Charrière, Pacific Fiction, 2016. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Around the diving bell are 146 coconuts from the Bikini Atoll. Encased in lead, they form the Pacific Fiction installation. The metal suggests both a protection from further radiation and the possibility of using them as bomb in echo of the colonial violence that scarred the region. Coconuts are a food staple and a symbol of life in the region. They’ve now become a radioactive hazard.

Other work in the exhibition continued the Anthropocene narrative but moved to other shores…

Julian Charrière,

Polygon X, 2014

Julian Charrière, Polygon XII, 2014

Julian Charrière, Polygon XXIX, 2014

Also known as the Polygon, Semipalatinsk in the steppes of eastern Kazakhstan was the Soviet Union’s main nuclear test site from 1949 until 1989. During these 40 years, they operated 456 nuclear tests, including 340 underground and 116 atmospheric explosions. The extent of the radioactive contamination on the environment and on local population was not fully known for many years.

Charrière travelled to Kazakhstan and used analogue photography to capture the sites. He then exposed the negatives to radiation. The printed images evoke Bernd and Hilla Becker’s documentation of abandoned industrial structures. Only the white spotting caused by the radiation indicate that the subjects of the images have a far more sinister story to tell.

Julian Charrière, Savannah Shed. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Julian Charrière, Savannah Shed. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Alligators, like other animals living near the Savannah River nuclear weapons site, bear the physical traces of half a century of nuclear weapons production and the occasional dumping of contaminated waste in unmarked pits that were not secure enough to keep highly toxic material from spreading into soil and groundwater. Every year, scientists capture and test thousands of animals to assess the progress in the cleanup of the area.

Charrière reconstructed the set-up of scientific testing which, according to the artist, took place after an accident in the area in 1964. The researchers released an alligator into the wild, captured it again and then they measured its level of contamination.

Julian Charrière, Somehow, They Never Stop Doing What They Always Did, 2019. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Julian Charrière, Somehow, They Never Stop Doing What They Always Did, 2019. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Julian Charrière, Somehow, They Never Stop Doing What They Always Did, 2019. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

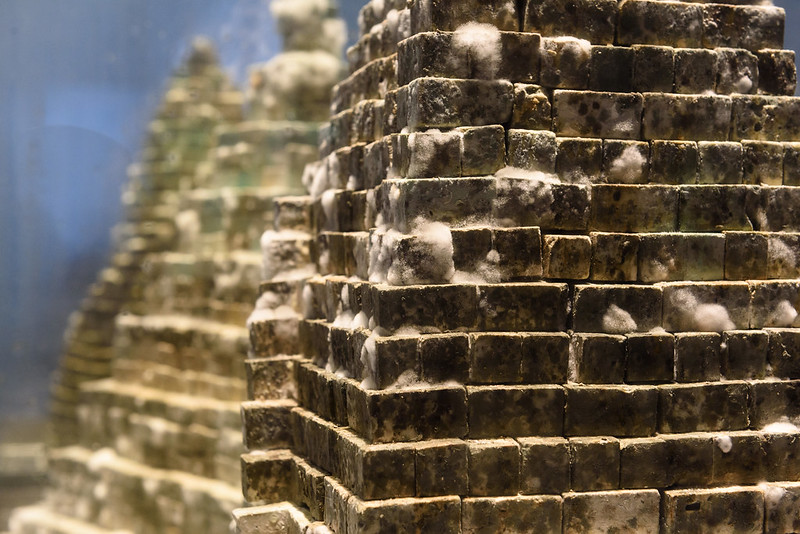

Inside each vitrine of the installation Somehow, They Never Stop Doing What They Always Did are pyramids that recall ancient monuments. They are made from plaster mixed with fructose and lactose, plus water that comes (or so the description says) from major rivers such as the Nile, Euphrates and Yangtze. Over time, bacteria grow on them and slowly erode the structures. Just as the ancient civilisations that rose along these rivers declined, the sculptures will eventually collapse.

From the Tower of Babel all the way to the decaying landmarks of the nuclear age, Charrière traces an unbroken line of ingenuity mixed with hubris, destined to fall apart and to follow the rules inherent to the matter that constitutes them.

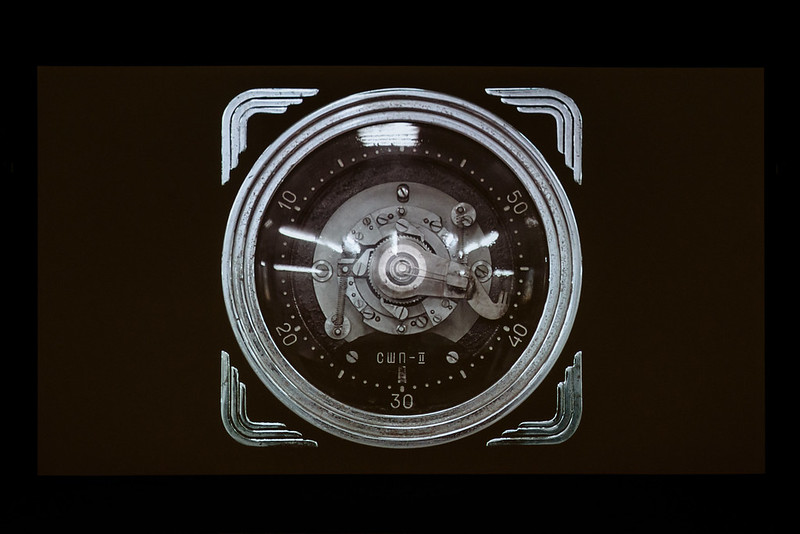

Julian Charrière

, Somewhere (video still), 2014

Julian Charrière

, Somewhere, (video still), 2014

Julian Charrière

, Somewhere, (video still), 2014

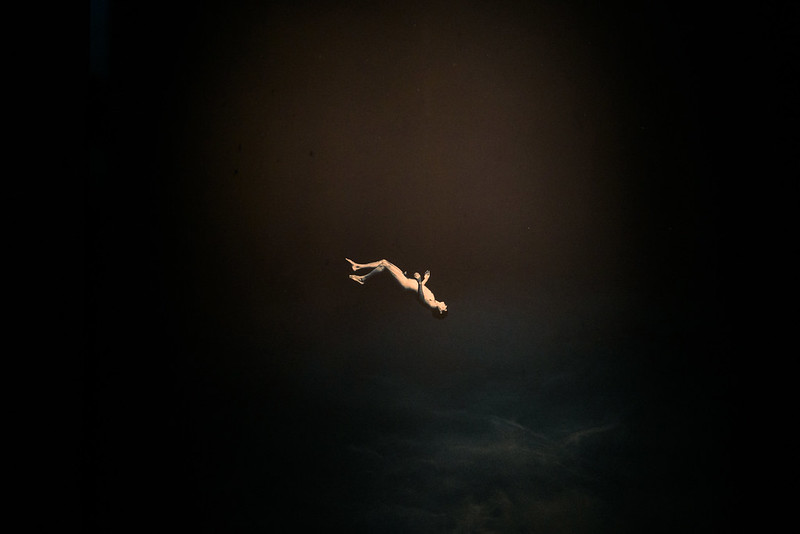

Julian Charrière, Where Waters Meet, 2019 | © the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Where Waters Meet is a series of eerie photos of naked bodies diving deep into cenotes in Yucatan, Mexico. Rather than descending into the water filled caves, their bodies seem to float onto a delicate, underwater cloud called chemocline.

Julian Charrière. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere, installation view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. Photo: Giorgio Bianchi, Comune di Bologna

Julian Charrière. All We Ever Wanted Was Everything and Everywhere was curated by Lorenzo Balbi and exhibited at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna over the Summer.