I discovered Jeremy Hutchison’s work in 2011 when he was exhibiting a series of laughable objects he had commissioned to manufacturers around the world. Not only did he ask them to fabricate items that would be unusable but he also requested that each worker had full license to decide what the error, flaw and glitch in the final product would be. Hutchison ended up with a collection of dysfunctional objects and prints of online exchanges with baffled factory managers. Err is an artwork that’s both ridiculous and profound. Behind its perfectly impractical combs, chairs, skateboards and trumpets, lay moments of poetry within the perfectly oiled machine of globalization and an elusive portrait of the anonymous factory workforce that manufacture all the consumer goods we don’t need but have been conditioned to yearn for.

Jeremy Hutchison, ERR, 2011. Untitled (made by Carlos Barrachina, Segorbina de Bastones, Segorbe, Spain)

Jeremy Hutchison, Movables, 2017. Fondazione Prada curated by Evelyn Simons. Photo by Paris Tavitian

At the time, I was expecting Hutchison to be a one hit wonder. I liked Err so much, i imperiously decided the artist would never be able to live up to everyone’s expectations. And yet, over the years, he kept on creating artworks that “explore improper arrangements of labour, language, behaviour and material to produce crises.” Artworks that proved my instincts wrong again and again: canvases involving BOTH an investment banker and an Occupy protestor, an exhibition orchestrated by members of the Sapporo Police Department, a video starring employees of a peanut factory without peanuts and a series of consumer goods that explore the (possible) “well-meaning dictatorship” of design.

Whether it meditates on the condition of the worker or investigates the recuperation of anti-capitalistic aesthetics by capitalism, Hutchison’s work is always imbued with humour and compassion. He’s having a few exhibitions across Europe this month. One of them is Transnationalisms which opens this week at Furtherfield in London. I liked Aksioma‘s version of the show in Ljubljana so much, i thought i’d use the London edition of Transnationalisms as an excuse to get in touch with the artist.

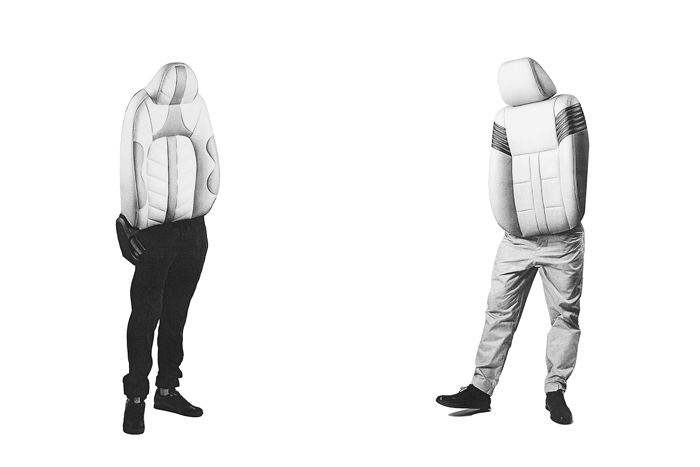

Jeremy Hutchison, from the series Movables, 2017. Courtesy the artist

Jeremy Hutchison, from the series Movables, 2017. Courtesy the artist

Hi Jeremy! Your project Movables will be part of the Transnationalisms group show that opens this week at Furtherfield in London. I find the work very moving. You sourced an image from the Daily Mail – a website that spreads hatred and contempt towards immigrants – and you used this as a starting point to question the regulations over the freedom of movement. Can you tell me more about this work?

Yes: I came across this photo on the Daily Mail website. It had been taken by police at a border point somewhere in the Balkans. The image showed the inside of a Mercedes: the headrests of the front seats had been torn open by police, revealing a human body hiding inside each seat.

This photograph testifies to a reality where human bodies attempt to disguise themselves as inanimate objects, simply to acquire the same freedom of movement as consumer goods.

In Movables, I translated this absurdity into a series of photo collages. They combine elements of high-end fashion shoots and car adverts – enacting an anthropomorphic fusion between human bodies and consumer products. The results are sort of uncanny. They appropriate a familiar visual language, but distort it to present a series of freaks. In doing this, I wanted them to embody a contradictory premise of global capitalism – with respect to the freedom of movement. Capital requires ‘free’ individuals to function as cheap labour forces. But it simultaneously needs to restrict their movement since it can’t offer the same freedom to everyone.

Jeremy Hutchison, Fabrications, 2012-16. EVA Biennale curated by Koyo Kouoh. Photo by Miriam O’Connor

Jeremy Hutchison, Fabrications, 2012-16. Courtesy the artist

Jeremy Hutchison, Fabrications, 2012-16. EVA Biennale curated by Koyo Kouoh. Photo by Miriam O’Connor

You are currently showing Fabrications at Division of Labour. For this project, you spent time in a jeans factory in Palestine and asked the workers to make jeans that translated what it was like to make jeans in Palestine. How did they react to your request?

Well, this project started with a conversation I had with the factory manager. He showed me a photograph of an Israeli tank, parked outside the factory. Its cannon was pointed directly at the building. He said it was hard to describe the physiological effect of this experience: of working under the threat of total obliteration.

So I asked him if he could manufacture jeans that described it instead. He produced five pairs. Each was distorted into unwearable positions; monstrous contortions of human legs. In some ways, I think they point to the way in which trauma becomes inscribed on the body. Stress isn’t simply a psychological state, it’s an embodied experience. It becomes genetically encoded, and passed down through generations. I think these jeans describe something of this process; how history is inscribed on the body – producing material, anatomical realities.

Jeremy Hutchison, Fabrications, 2012-16. EVA Biennale curated by Koyo Kouoh. Photo by Miriam O’Connor

Jeremy Hutchison, Fabrications, 2016

The description on your website says that the “project constructs a counter-history of Palestine.” What do you mean by that? And how does Fabrications achieve it?

I’ve produced a number of projects in the Middle East. And the more time I spend there, the harder it becomes to think in terms of facts, history, or truth. Whatever position you take, it’s subject to a myriad of subjective distortions.

So in this project, I accelerate this process. Via a series of heavily retouched images, I suggest that Palestine was once bright blue, like the sky. Vast quarries of dazzling indigo rock spilled out of the land. They used the indigo to dye jeans. In turn, this attracted foreign investment, colonisation – and ultimately the Indigo Wars.

Of course, this is absurd. Indigo isn’t a mineral, but a flower. There were no indigo mines, no Indigo Wars, and Palestine was never blue. By invoking this fictitious narrative, the work invites a critical reflection around the construction of historical discourse, alluding to the distortions that take place in the structuring of history. But ludicrous as it may be, this falsified history operates in a tension with contemporary reality. After all, Palestine’s representation in Western media is plagued by uncertainty. Its geopolitical status is perpetually ambiguous. So the work concentrates this state of uncertainty into a poetic delusion. The land itself becomes a vessel for the imagination.

I’ve exhibited this work several times – including the ICA in London, the EVA Biennale in Ireland. What’s interesting is how often it passes for historical fact: how readily a fictitious history is unquestioningly accepted by a sophisticated audience. Perhaps this is part of the project’s success: it performs its own problem. It demonstrates how truths can be manufactured and circulated, like consumer goods. And it points to the role of white British men in doing so.

Jeremy Hutchison, In heaven people play peacefully sometimes people helping each other love making and working together peacefully, 2016. Photo by Rebecca Lennon

Jeremy Hutchison, In heaven people play peacefully sometimes people helping each other love making and working together peacefully, 2016. Photo by Rebecca Lennon

I’m interested in your work In heaven people play peacefully sometimes. In this project you invited four Task Rabbit workers to paint a mural as if they were a single person. Does the performance point to potential new forms of collaboration that would somehow counterbalance the new tech-mediated trends in labour that dehumanize workers and reduce them to just another cog in the machine?

In many ways, yes. I wanted to explore a situation that rehearsed a kind of solidarity between this distributed workforce. A physical solidarity among workers in the gig economy. None of them had ever worked alongside another ‘Tasker’ – in fact, they’d barely even met one. And this is precisely the point. The fragmentation of workers in the gig economy means that they are pitted against one another. Their individual success depends on their ability to outperform their peers – not to organise or collaborate with them.

The project was triggered by something a gig worker told me. He had stopped using the leather case for his iPhone. Why? Because the time it took to open the flap would result in him losing a gig. During that split-second delay, another worker would get there first. The apparently casual working conditions of the gig economy don’t produce casual workers, but individuated neurotics, fixated on data, personal rankings and milliseconds.

So in this sense, I’d agree with you: we can see the gig worker as a ‘cog in a machine.’ But do the new tech-mediated trends in labour de-humanize workers? Not always. In fact, I think it’s precisely the workers’ humanity – their human capital – that is often foregrounded in these labour platforms. Their personality, social attributes and subjective traits are commodified in their profile pages. So rather than de-humanising workers, I would argue that digital technology does the opposite. It obliges us to amplify our subjective human traits: to exaggerate our individuality and present it as a quantifiable economic resource.

With each new project, it seems that you uncover and investigate a new aspect of production, of consumption but also of labour and how technology is changing its dynamics and logics. How does it affect you personally? How does it change (if it does) the way you shop, work, relate to others?

Well I buy fair trade, I don’t eat meat and I boycott fast fashion. But I have an iPhone that’s stuffed with conflict minerals from Congolese mines. Like everyone else, I’m inextricably complicit in these exploitative networks of production and consumption. Try as we might, it’s extremely difficult to adopt a position outside them. I guess I’m interested in understanding my own complicity and articulating this; to trace out a relationship between my own lifestyle and a global problematic. How do my consumer choices relate to current humanitarian catastrophes? How does the stuff I buy feed off racial hierarchies, economic inequalities, and exploitative supply chains? Consumer objects are portraits of these things – and like most people, my home is filled with them. So I think my art practice helps me to think about the invisible structures that support my privileged Western position. These structures are man-made: they can be re-shaped and distorted by us. I think art can be a way to think through these questions.

Jeremy Hutchison, Monolimum, 2017

Jeremy Hutchison, Limomolum, 2016, Documentation of linocutting workshops at Trust In Fife housing shelter, Kirkcaldy

I learnt a lot from the text you wrote for Limomolum. I found it very moving too. Is this all based on your own experience/relationship with linoleum? Or did you mix stories you heard while in Kirkcaldy?

Thanks Regine, yes all the texts draw on my own experience. Limomolum explores a town called Kirkcaldy on the East coast of Scotland. For two centuries, it was a very productive, affluent place: home of the global linoleum industry. But in the eighties, it started to fall apart. Today Kirkcaldy is largely a place of unemployment and drug addiction.

My father was born there. His family owned a linoleum factory, but he was estranged from them. So I grew up knowing very little about the town. So I took the train up there, and set out to explore. One morning I wandered into the homeless shelter and started chatting to a couple of residents. This was the beginning of a year-long project: we turned the shelter into a performance centre, and the employment support clinic into a linocutting workshop. The work was exhibited in the Kirkcaldy museum.

So yes, I wrote a publication to accompany this show. I wanted to try and capture the complexity of this place, without reducing this constellation of histories and economies. When projects become as extensive as this one, there’s a temptation to make the work complex. I find that writing helps to keep things simple.

Jeremy Hutchison in collaboration with James Inglis and Deone Hunter, Limomolum, 2016. HD video still

Jeremy Hutchison in collaboration with James Inglis and Deone Hunter, Limomolum, 2016. HD video still

I only have an external and superficial perspective on your work of course but it seems to me that you manage to establish a relationship based on mutual trust and respect with the workers (or unemployed people) you feature in your works. How do you manage to convince them that you’re not there to exploit them and make a spectacle of their life? How much efforts, strategies does that require?

These are complex ethical questions. How do I convince people to work with me? How do I avoid making a spectacle of their lives? I don’t think I necessarily do. If we engage with them squarely, the exchanges that take place in social practice are often loaded with asymmetrical power relations. Value can be produced in tacit, invisible ways. Rather than smoothing over awkward socioeconomic imbalances, I try fold these questions into the work. I think the more interesting answer is to be honest, about when social arrangements become exploitative, or turn sour, or fail. Despite my best efforts to anticipate ethical problems, sometimes I fall right into them. I don’t think the answer is to avoid these messy situations, but to move through them.

You were recently on residency in Japan. Can you tell me what you were doing there?

I went to Japan to think about labour conditions. I wanted to explore a country that even has a word for work-induced death: karoshi. Given the relentless pressure to work, what will happen when jobs are automated? How will Japanese people navigate the existential challenge of a post-work condition? What will they do?

This resulted in a project called HumanWork. Borrowing its name from the premier recruitment agency in Japan, it explores the process of recruiting someone for a week of non-productive labour. The project was commissioned by Arts Catalyst / S-Air, and should be exhibited fairly soon. Oh, and I also made a project with the Sapporo Police Department. But I’ll tell you about that another time!

Thanks Jeremy!

Transnationalisms, curated by James Bridle, is at Furtherfield in London, from 15 Sep until Sunday 21 Oct 2018.

Jeremy Hutchison’s work is also part of APPAREL at Division of Labour in Salford, Manchester, Jerwood Drawing Prize at Drawing Projects in Trowbridge, Market Forces at HeRo Gallery in Amsterdam and many more i’m sure.

Transnationalisms is realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).

Previously: Transnationalisms – Bodies, Borders, and Technology. Part 1. The exhibition and Err (or the creativity of the factory worker), a conversation with Jeremy Hutchison.