In January 2017, artist Louise Ashcroft invited herself to be an artist in residency at Westfield Shopping Centre. That’s the mega mall in Stratford, East London. Its retail area is as big as 30 football pitches (says wikipedia), it has famous chains of fast fashion & fast food, screens budget-bloated blockbusters, rents kiddy cars and boasts some seriously boring ‘public’ artworks. Because there’s nothing remotely boring, mass manufactured nor glittery about her work (and also because she is quietly plotting the demise of capitalism), Ashcroft spent her time there undercover, pretending she was only looking for a bit of shopping fun.

The artist will present the result of her stealth research this week at arebyte in Hackney Wick, a five-minute walk from Westfield. Some of the works she developed at the shopping mall include a transposition of words from slogan fashion T-shirts on traditional narrow boat signs, offers to exchange ‘happy’ meals toys with more ‘soulful’ artist-designed toys, seditious retail therapy sessions, bookable tours of Westfield where she will guide participants through playful (pseudo)psychoanalytical activities, ‘mallopoly’ cards that invite shoppers to use the mall and its contents as a material, etc. Oh! and, since the Westfield area is the home of grime she also compiled words from Argos shopping catalogues into a cut-up text and grime artist Maxsta recorded it as a track.

This is not Ashcroft’s first incursion into the magical world of retail poisoning. She regularly smuggles unfamiliar-looking African vegetables into supermarkets and then throws the store in disarray when she attempts to buy them (Vegetable, 2003-17.) Two years ago, she spent time on another unsanctioned residency at Stratford Centre, a 1970s shopping precinct right in front of the flashy Westfield mall. She analyzed the centre’s marketing philosophy of “taking something negative about yourself and owning it” in the first hilarious TEDx talk i’ve ever seen:

Louise Ashcroft, Shopping and subversion at TEDxHackneyWomen

Ashcroft‘s solo show I’d Rather Be Shopping opens this Friday at Arebyte gallery as part of the gallery’s 2017 programme, Control. I asked her to take us through her research inside the best air-conditioned workshop an artist could hope for:

Louise Ashcroft, Stratford Works Trailer

Hi Louise! You had a residency at the Stratford center a couple of years ago. If i understood correctly, you simply invited yourself. It wasn’t an official one. Did the same happen this time in Westfield Center?

Yes, I invited myself to hang around the Stratford centre for some weeks. I’d noticed that it’s a space of resistance- people who can’t or don’t want to opt into the big capitalism of the Westfield mall hang out here, sell things, buy things; and the conventions of modern marketing are repeatedly broken.

It offers an alternative version of capitalism in which street traders, local characters and loiterers coexist with chain stores in a way that Westfield wouldn’t allow. The Stratford Centre is anarchic compared with Westfield – it shows its imperfections, has nothing to hide, whereas its megamall neighbour tightly controls the shopper’s experience so that we only see a partial view of the system and its wider social impact.

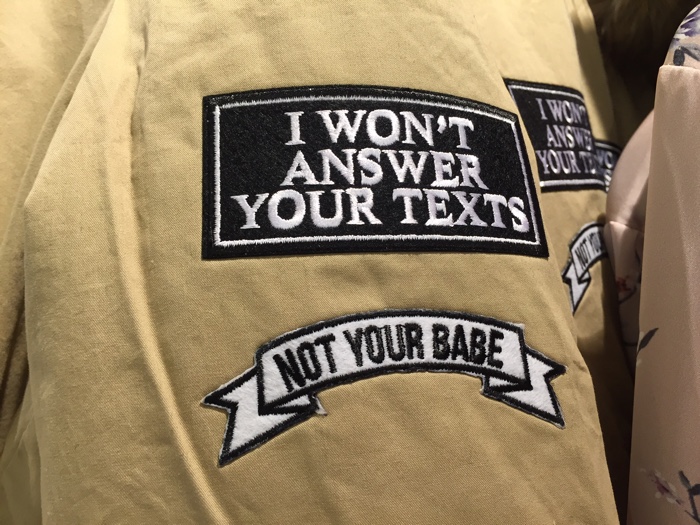

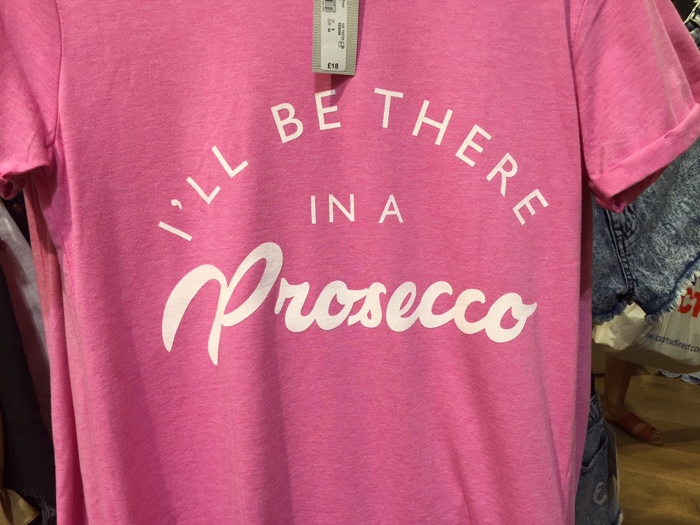

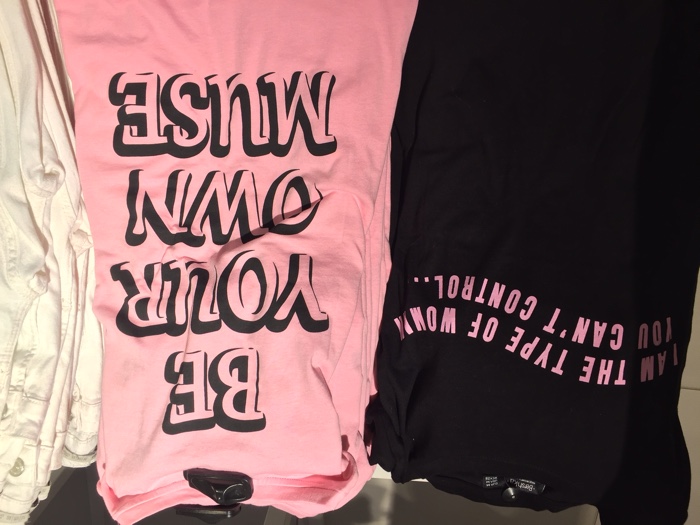

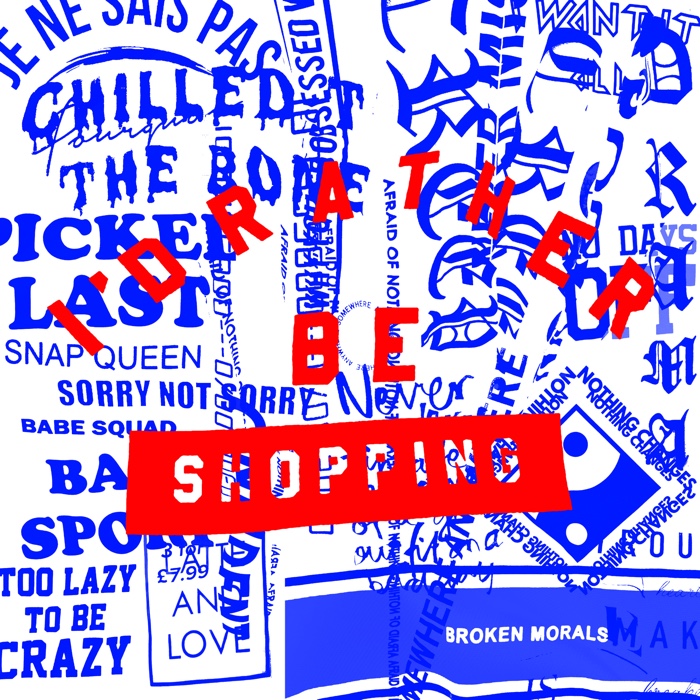

Westfield also has peculiar marketing strategies, but their bizarre qualities come from their efforts to conceal darker truths. For example, the biodiversity themed playground, the empty bee nesting boxes fitted into benches in the outdoor ‘street’ area, the plague of slogans featured on all the fashion at the moment- much of which features activist style slogans like ‘we are the future’ or ‘more bikes less cars’ or ‘feminist’. Despite the fact that these items themselves are the causes of ecological issues and problematic body politics. Other fashion slogans are more pessimistic, as though referring resignedly to the impending planetary destruction that consumerism has brought about: ‘I sold my soul’, ‘the end is nigh’, ‘nothing changes’. etc. Some of the t-shirts voice the angry isolation of a relationships based on likes and swipes: ‘whatever I’ll just date myself’, ‘like is the new love’, ‘why you so obsessed with me?’ I’m quite fixated on the t-shirts, they’re like our cultural stream of consciousness. Many express a sort of depressed helplessness: ‘too lazy to be crazy’, or ‘stay in bed’; whilst many celebrate neoliberal ambition and endless self-improvement: ‘no days off’, ‘run’, ‘I want it all’.

I found it hilarious that all the designers seemed to have taken a holiday and set up some sort of algorithm that prints hashtag phrases onto the cheapest plain t-shirts and sells them like hot cakes. It’s like wearable social media, a walking Facebook wall. I figured that these phrases were the key to the subconscious of society at this point in time, and I wanted to analyse this types of phrases that were being selected.

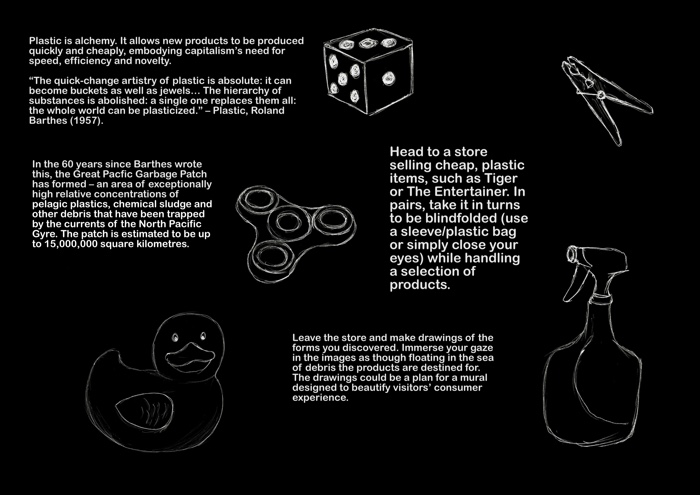

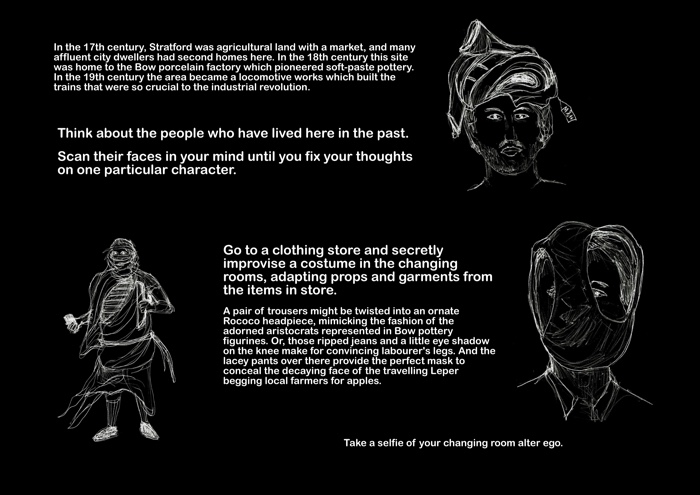

There so much more though. The Mallopoly game I’ve made (which will be given away free to all visitors to the show and people in Westfield) is a self-led series of activities to carry out in the centre, using the products and architecture as materials/props for challenges which each relate to an aspect of the shopping centre’s socio economic DNA. I think encouraging people to behave in different ways there is better than describing what I think is going on. I hope it’s not too didactic, as the tasks all relate to problems like seed rights, pollution, plastic and commodities trading. The tasks are very playful but there’s something quite futile about them too, in the face of these big issues. I want to simultaneously make the players feel liberated from the hegemony of the space but also powerless because the rebellious tasks (mainly involving role play, mime, sensory experiments, disguise, drawing, sound) are all quite benign and impotent really. A lot of my work is hedonistic yet melancholy, maybe that’s what Westfield is like too.

Mallopoly card

Mallopoly card

Also i was wondering how you behaved during this residency. Did you pretend to be a shopper like anyone else? Did your activities stand out in any way?

I had to pretend I was a shopper so I didn’t get in trouble, particularly when filming or watching people. YouTube vloggers have been banned from Westfield because many were playing pranks. There are a lot of security guards and I was stopped several times and asked if I needed help (or basically asked why I was behaving differently by loitering or photographing). I often get mistaken for staff in some shops, particularly sports shops, if I was wearing casual clothing. I’d originally hoped to find ways of working in the shops as part of the residency but it was difficult to even have conversations with shop assistants – it’s very much about efficiency in a modern shopping centre (not like the social space shops were when I was growing up in the north of England – my mum would spend hours chatting to shop assistants).

Louise Ashcroft, Unicorns of Westfield, 2017

Like many shopping centres, Westfield Stratford is a very loud place, especially visually. A fairly short amount of time in a shopping mall leaves me quite depressed. Since you spent so much time there, i was wondering if the experience affected your senses and mental well-being in any way?

I felt really lonely there. I remember once eating a packed lunch in the food court and really wanting to start a conversation with an old lady who also looked lonely but there was something about the place that made me nervous to do that – I felt like I’d come across as suspicious (I should have just gone for it). I listened to a lot of teenage conversations in the food hall- chat about social media interrupted by bleeps of social media. It’s definitely a social space if you’re with your group but it’s not the kind of place where people chat to passersby like they do in the Stratford centre. I talked to a middle aged woman for a while, because she was doing market research and I thought I could turn it into a more interesting conversation, but she had targets to meet and was really just interested in following the script that was popping up on her iPad questionnaire. I suppose people expect that if you try to talk to them in this space then you’re motivated by a financial transaction in some way. The first couple of months I found it really hard to be there, but now I feel I could do with much more time. I think the ‘retail therapy’ and performances I’m doing with individuals and groups of audiences will be the point when all of the research comes together in a way that feels really dynamic and impactful.

I’m a believer in the power of confusion, and when a group behaves unusually it provokes those involved and their witnesses to question what’s going on, and to question the whole environment they might have taken for granted.

I’m interested in the research you did with UCL students at The Institute for Global Prosperity to develop a “Deviant Planning Committee”. Are you going to publish online the inventory of deviations you compiled with them? Can you give us examples of some of these deviations?

Having spent so long in the mall, I invited these students, who were from various disciplines (mostly non arts subjects) and were on a summer school, to take my place for a day and hunt for opportunities for deviation within the Olympic park. They weren’t focusing so much on the shopping centre, rather its wider context. Many of the students found it very difficult, and a lot of what came back was ideas for business opportunities or ways of making the place more pleasant. Some of the responses were more critical though, and asked questions, for example about the value of the natural resources such as water and land, about the ways the security staff operate and how they might be used differently, or the names of the streets, or how busy the body is encouraged to be in this space of consuming and exerting energy.

There is a lot of humour in your work. Far more than in capitalism, the theme you’re exploring in many of your works. How do these two relate? How can humour be a useful instrument in subverting capitalism?

I get the same dopamine hit from the punchline of a joke as I do when a concept clicks into place in a conceptual artwork or theoretical text. Comedy is philosophy at its most efficient, with all the excess cut off. Jokes often happen when contrasting ideas come together and connect as part of the same thought, creating a chemical reaction which shifts their original status. If applied to our surroundings I think this is a powerful recipe for challenging the status quo, so I collage together what’s around me to make comic situations which unfold in public. Subverting ordinary situations is inherently funny- it’s what clowns have done for centuries, often literally reversing ordinary behaviour. Humour lets the viewer in because it’s pleasurable to laugh and because it shows that the artist is aware she is not special (a lot of art puts itself on a pedestal and I think this alienates people). It’s my failure to overthrow capitalism and the absurdity of my attempts to do so that make it funny.

There is also a level of naivety which helps me to get away with public actions in the first place. Beauty or technical excellence traditionally provide entry points for the viewer’s contemplation, but these are often focusing on impressing the viewer. My work is ordinary, it’s made with low value materials, it doesn’t require expertise, it often goes wrong and yet it reports back on these inadequacies with glee, a bit like how the Stratford Centre owns its weaknesses.

During these shopping mall residencies you’ve learnt a lot about marketing. I’m wondering if you’re not tempted to apply any of that in your art practice. Not so much in terms of content but as an instrument to advance your career, sell your work, turn you into a formidably marketable artist?

Marketable work tends to be work that has been completed and that it is possible to collect. I wrote a dissertation on wildness and ways of resisting being captured by the market. I only enjoy making work if I feel like it’s somehow transgressive, when it starts to feel like ‘work work’ I’m not interested any more. Wildness is an important part of the DNA of my practice. It’s what allows me to retain exteriority to the systems I analyse. Outsider status is fundamental to that. Even if I’m making objects they are always part of performative gestures and it’s not about finished objects but the effect they have in the moment. The traditionally painted signs featuring t-shirt slogans which I’m making for this show will all be given to the local boating community after the show. In an ideal world I’d have just painted directly into their boats. I love the idea of switching the fashion slogans and boat names.

You worked with grime artist Maxsta on a record inspired by your work at Westfield. How did the collaboration come about and what made you chose the Argos catalogue as a source for the lyrics? Is there a video of the track?

A lot of the pieces I’ve made for this show are collage-like, in that they take aspects of contrasting cultures and combine them. Like jokes do. I found out that this area is the home of grime music and i became interested in the anger in this working class genre and the way it rejects the blingy consumerism of commercial rap. Of all the catalogues in the mall, the Argos catalogue was most bountiful with evocative words I could cherry pick and bring together to make abstract lyrics. I approached a local grime station Don City Radio and they recommended someone but he didn’t get around to it and I couldn’t get through to him on the phone so I did some research and found a more experimental rapper then sent him a twitter message. He got the track to me within a couple of days and it is fantastic. He’s up for working on more collaborative stuff because the way I bring words together seems to work well with his phenomenal vocal abilities. It’s an exercise in appropriation really, but everyone’s appropriating everyone else, speaking through one another’s voices (the Argos copywriters, me, Maxsta). For me, the track reveals that what shops are really selling you are words and images – the materiality of most of the products is often generic (cotton, wheat, plastic, wood, metal…). The society of the spectacle and all that. Me and Maxsta are a pair of spectacles! Words are so rich and yet they’re all free and you can make them anywhere, anytime- that’s liberating. I’m a big believer in the power of parody, and mimicry, like the woman I heard on the radio yesterday doing Shakespeare in an Eastenders accent. By shifting the voice of something you reveal it for what it is.

What will the retail therapy sessions with Louise Ashcroft be like?

The retail therapy sessions will involve me and strangers (1-3 per session) completing a series of tasks in different shops and talking about the products we encounter, as devices for understanding our own lives and futures. We will begin with some exercises from Mallopoly the Westfield themed card game I’ve made which involves challenges like finding a product from as many countries as possible, making a noise track on our phones, dressing up as 18th century farmers in the fitting rooms, miming a coffee break, applying botanical classifications to the architectural decorations. All kinds of experiments, each of which relates to a problem with capitalism such as seed patents, waste or inequality.

Louise Ashcroft, Bread Suit, 2010

The bio on your website starts with the words “Recognising the power of small acts of resistance”. What can these small acts achieve?

Maybe just to remind us all to question everything and to see past the surface of things, deconstruct our presumptions about the world around us and reconstruct it more knowingly and more actively. An accumulation of small actions is the only way to change the world without becoming a replacement dictator. That’s why I hope my work isn’t preachy or didactic, I think empathising with one another’s weaknesses (mine especially) is crucial to making change happen.

And on top of your bio text, there’s “Nobody likes an activist.” But i feel that everyone wants to be an activist these days. Or at least pose as one. What’s not to like in an activist?

Once my dad said this so I wrote it down. I think he meant that people think activists believe that they’re better than everyone else. I wanted to remind myself that it’s ok not to be liked and that activism isn’t easy, even when it’s this small. If you’re going against the flow then that saps your energy, so reminding myself if that helps me keep going. I’m naturally stubborn and contrary, so the idea of going against the flow appeals. It’s not just for the sake of it either- as artists we have the duty to voice ignored, invisible or repressed truths. Our senses are heightened, we’ve trained for this – like sniffer dogs it’s our job to alert people to unnoticed things and then let them respond to that however they feel.

Thanks Louise!

Louise Ashcroft solo show I’d Rather Be Shopping opens at Arebyte gallery in Hackney Wick on 25th August 2017.