In medieval Europe, alchemy was the Ars magna, the ‘Great Art’.

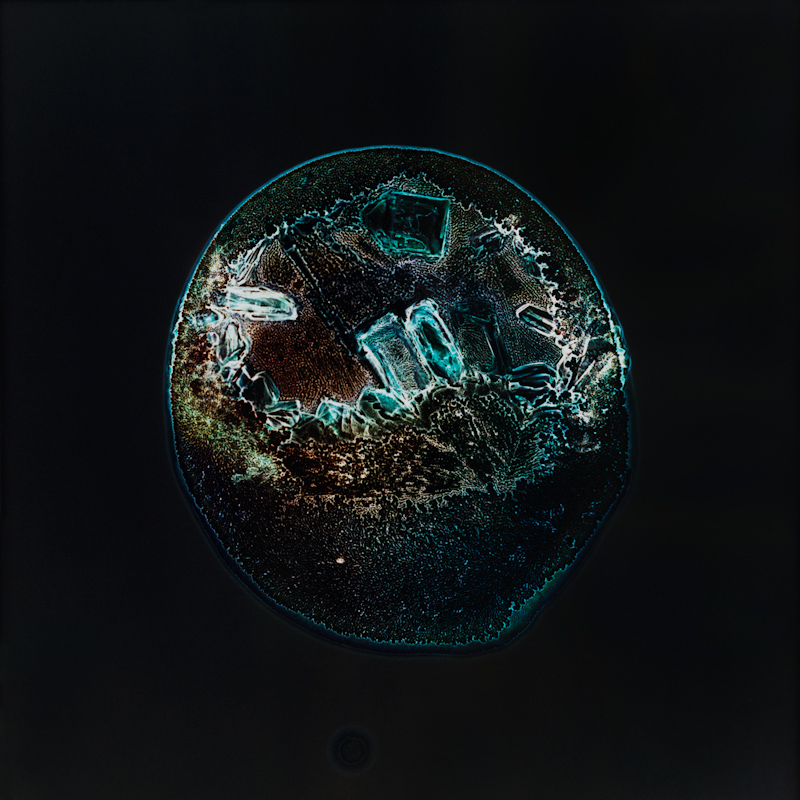

Sarah Schönfeld, All you can feel, Crystal Meth (Planets), photo-pharmaceutical series 2013. Crystal Meth on photo-negative, enlarged as c-print

Alchemie. Die Große Kunst/Alchemy. The Great Art (exhibition view.) © Photo: David von Becker for Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Alchemy. The Great Art, a show which will close this Sunday at Berlin’s Kulturforum (i’m writing this post in a hurry in the hope that some of you might still catch it) explores the enduring relationship between alchemy and art. The alliance between the two fields is an intimate one: both art and alchemy are about creation, both rely on experimentation, knowledge-seeking and passion.

Mixing historical artefacts and contemporary artworks, the exhibition also rehabilitates alchemical practices and illuminates their legacy. We often dismiss alchemy as a charlatan pseudo-science which sole purpose was chrysopoeia (the making of gold.) Most of its adepts had a very modern pursuit though: they wanted to imitate the divine act of creation itself and even to surpass it. This drive to transmute existing matter into a man-made compounds still influences many artists (and scientists) today, especially the ones whose work investigates processual transformation of material.

The parallels between the old-time practice and contemporary life do not end there. The need to mine the alchemical “first matter” (prima materia) from below ground echoes our ‘extractivist’ society. As for the creatures of doctors Faustus and Frankenstein and the disquieting new forms of life elaborated in research laboratories, they are the scions of the homunculus, this tiny human being grown in a glass jar and depicted in medieval manuscripts.

While searching for the philosopher’s stone, the elixir of immortality or the panacea, some experimenters made – sometimes by chance – discoveries that paved the way for modern chemistry and pharmacology. The by-products of alchemists’ exercises, such as porcelain, gold-ruby glass and phosphorus, are still very much valued today.

Alchemy. The Great Art manages to pack the historical, the spiritual, the hocus-pocus and the protoscience dimensions of alchemy into a rich and fascinating show. My pitiful article, however, doesn’t have the ambition to cover the multiple perspectives on alchemy presented at Kunstforum. It will mostly look at a few artworks i discovered while visiting the show:

Sarah Schönfeld, Hero’s Journey (Lamp), 2014. © Sarah Schönfeld

Sarah Schönfeld, Hero’s Journey (Lamp), 2014. © Sarah Schönfeld. Photo via tissue magazine

One of the focal points of the exhibition is Sarah Schönfeld‘s Hero’s Journey (Lamp). Over a period of ten weeks, the artist asked partygoers of Berghain, allegedly Berlin’s most exclusive nightclub, to donate their urine. She then treated the yellow liquid with an antimicrobial agent often used as a preservative in the cosmetic industry.

The biological excretions are now contained inside an illuminated glass case. The urine shines like gold and constitutes a kind of monument to the club’s mythical status as well as to the ecstatic emotions induced by recreational drugs.

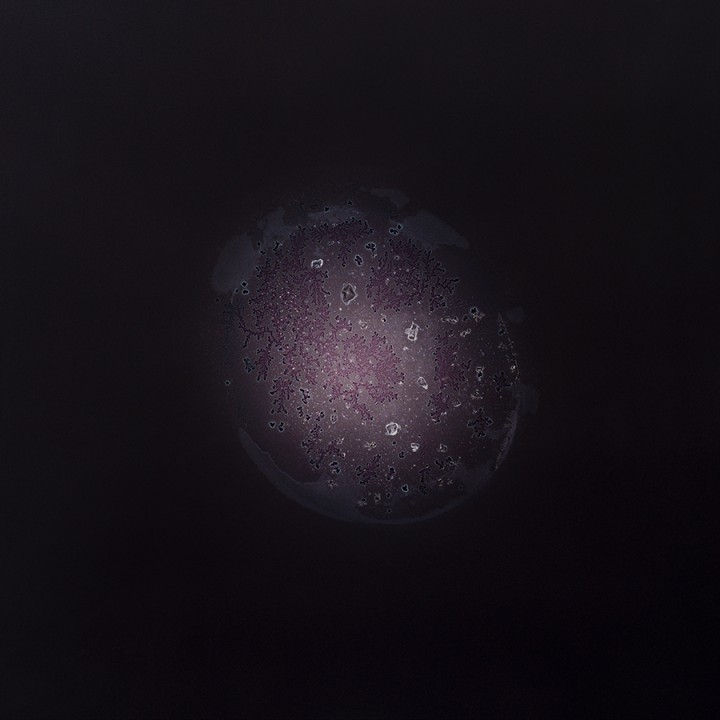

Sarah Schönfeld, Adrenaline – Adrenaline on photonegative analogue, enlarged. From the All you can feel series

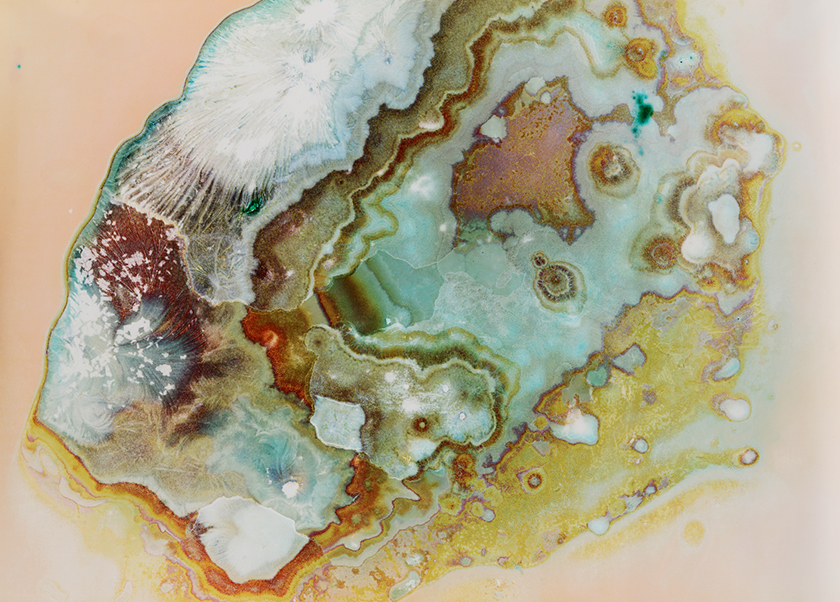

Sarah Schönfeld, MDMA on photonegative analogue, enlarged. From the All you can feel series

For the All You Can Feel photo series, Schönfeld developed a process that she calls “modern alchemy.” She sprinkled all sorts of mind-altering substances, from caffeine to neurotransmitters, onto photo negatives. The results of the chemical reactions between the negative’s emulsion and the drug was then submitted to photographic process.

When asked by VICE how she managed to create images that match so adequately the feeling that these various drugs impart, the artist answered:

Well, I didn’t think that when I first produced the work, but after I published the book (also called All You Can Feel) a lot of people said yes, this is how it feels. And what was really interesting is that I got a call from a drug rehabilitation center and they said that they had run their own little experiment. Without explaining the images, they had shown the book to their patients and asked them to pick a favorite. Every single one of them chose their drug of dependence, with 100 percent accuracy. Even the secretary who only ever drank coffee chose caffeine.

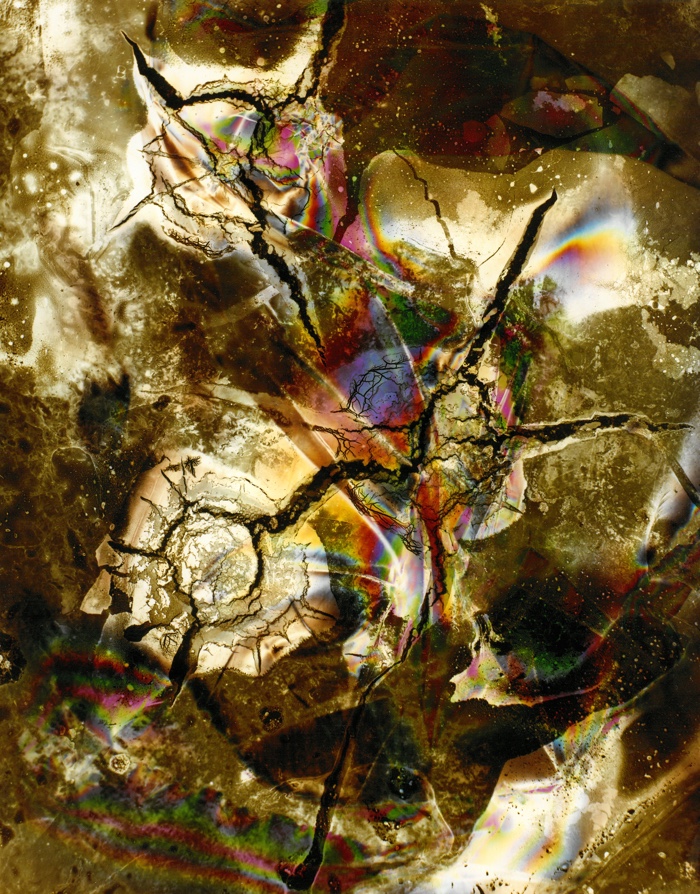

Heinz Hajek-Halke, Untitled, 1950-1970. © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Collection Michael Ruetz / Agentur Focus

It was particularly interested in the suggestion that photography, an artistic discipline born out of darkrooms and chemical laboratory experiments, used to be surrounded by an alchemical aura. Schönfeld’s work evoke photograms, the photographic image made without a camera by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper which is then exposed to light. There were some beautiful examples of photograms by Walter Ziegler in the show but i can’t find any image of them online, alas!

Heinz Hajek-Halke also experimented with photographic processes, exposures, instruments and materials. To create his “colour lucidograms” series, he drizzled soot-blackened glass negatives with liquids such as turpentine to produce craquelure-like patterns as the original congealed.

Peter Fischli & David Weiss, Der Lauf Der Dinge/The Way Things Go, 1987

Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go) is a famous video that follows a 30 minute long, uninterrupted chain of physical and chemical experiments full of carefully prepared explosions, accidents, fires, etc.

The Ripley Scroll, 18th century (Mellon MS 41, Beinecke Library). Alchemie. Die Große Kunst/Alchemy. The Great Art (exhibition view.) © Photo: David von Becker for Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The ‘Ripley Scrowle’ (detail), 18th century. Image: Beinecke Library

The ‘Ripley Scrowle’ (detail), 18th century. Image: Beinecke Library

The copy of the Ripley Scroll i saw at Kulturforum is one of the most exquisite artifacts i’ve seen this year.

There are some twenty copies of these alchemical scrolls in existence. Each of them is a variation on a lost 15th century original. The manuscripts use pictorial cryptograms to detail the various processes involved in the preparation of the philosopher’s stone.

Although they are named after the English priest, author and alchemist George Ripley, there is no evidence that he designed them himself. The link with the alchemist is that the elaborate imagery of the emblems derives from his verses.

Traité de Chymie, France, circa 1700, S. 10/11. © The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

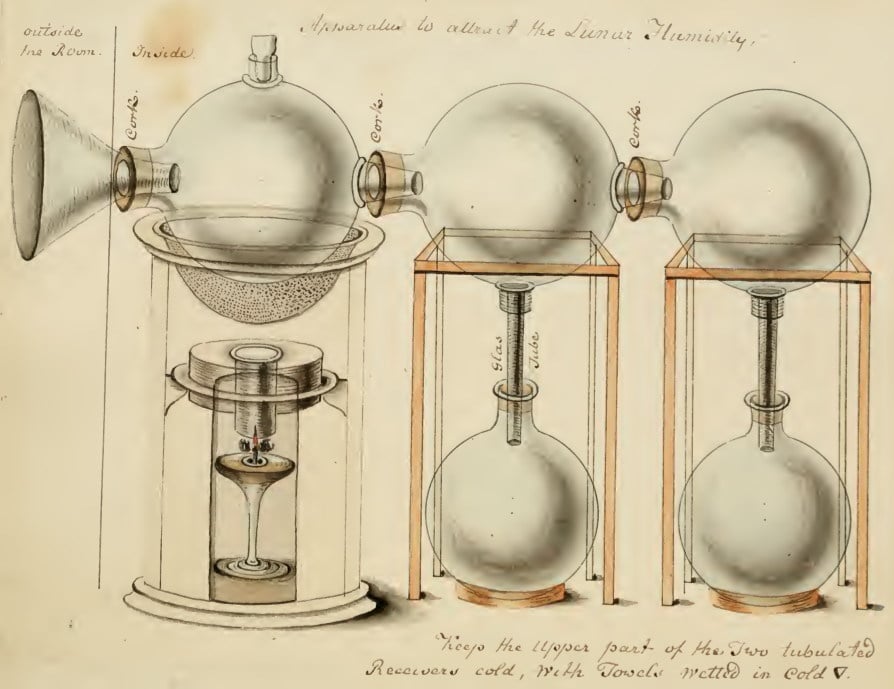

This watercolor shows that many early alchemists used instruments similar to the ones pharmacists or chemists would use later.

Natascha Sonnenschein, Paradies der Künstlichkeit, 2001. © Natascha Sonnenschein / VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2017

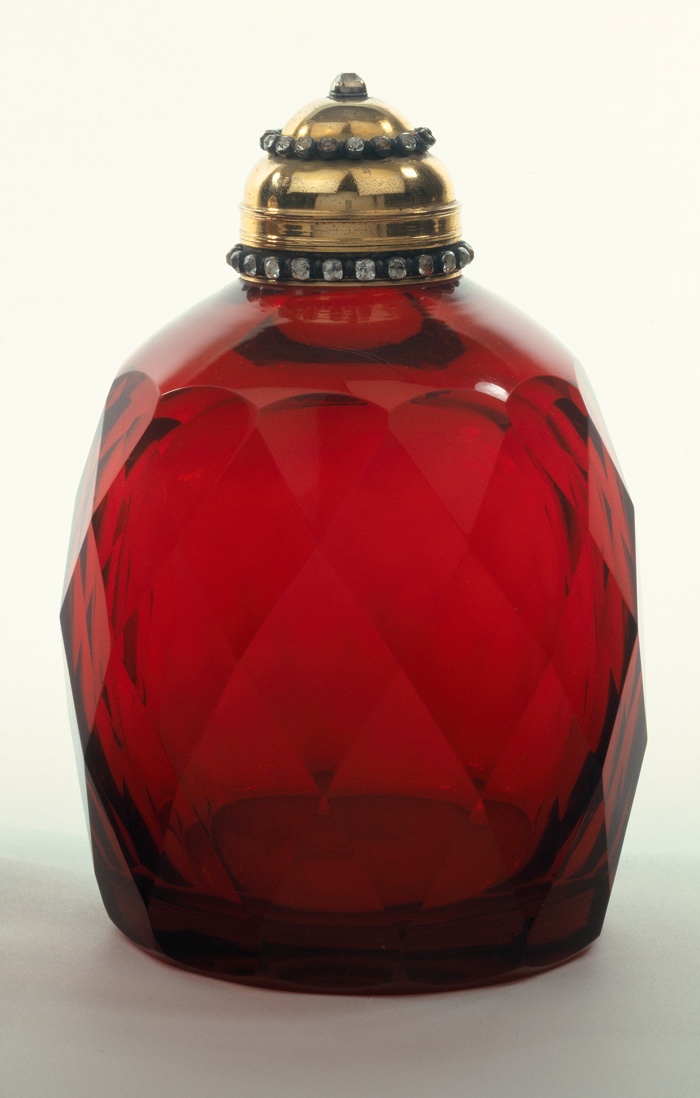

Facettierte Deckelflasche mit Montierung, circa 1700. © bpk / Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Sigismund Bacstrom, Device for Distilling Lunar Humidity, 1797

Johann Friedrich Böttger, Gold- and Silver nuggets, circa 1713. © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Porzellansammlung. Photo: Hans-Peter Klut, Elke Estel

One gold, one silver nuggets, allegedly transmuted by Johann Friedrich Boettger for King August of Poland in 1713. Boettger probably made them from ducats to win the King’s favour.

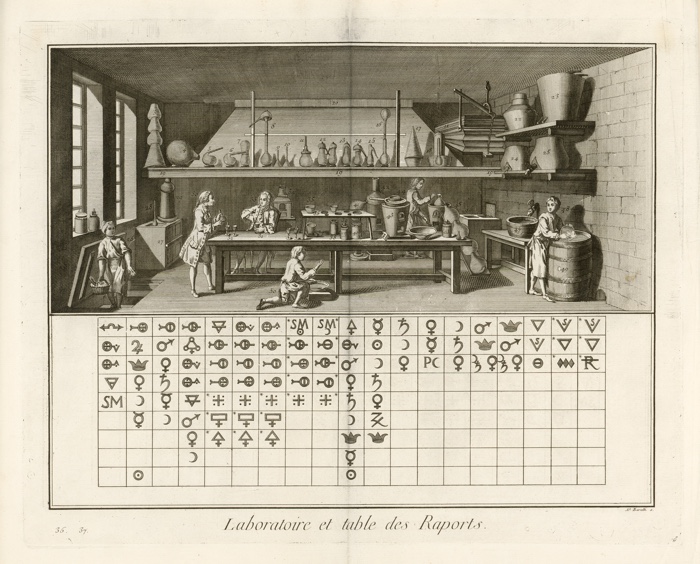

Louis-Jacques Goussier: Chymie, Laboratoire et Table des Rapports, in: Denis Diderot, Encyclopédie, 1771. © bpk / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek. Photo: Dietmar Katz

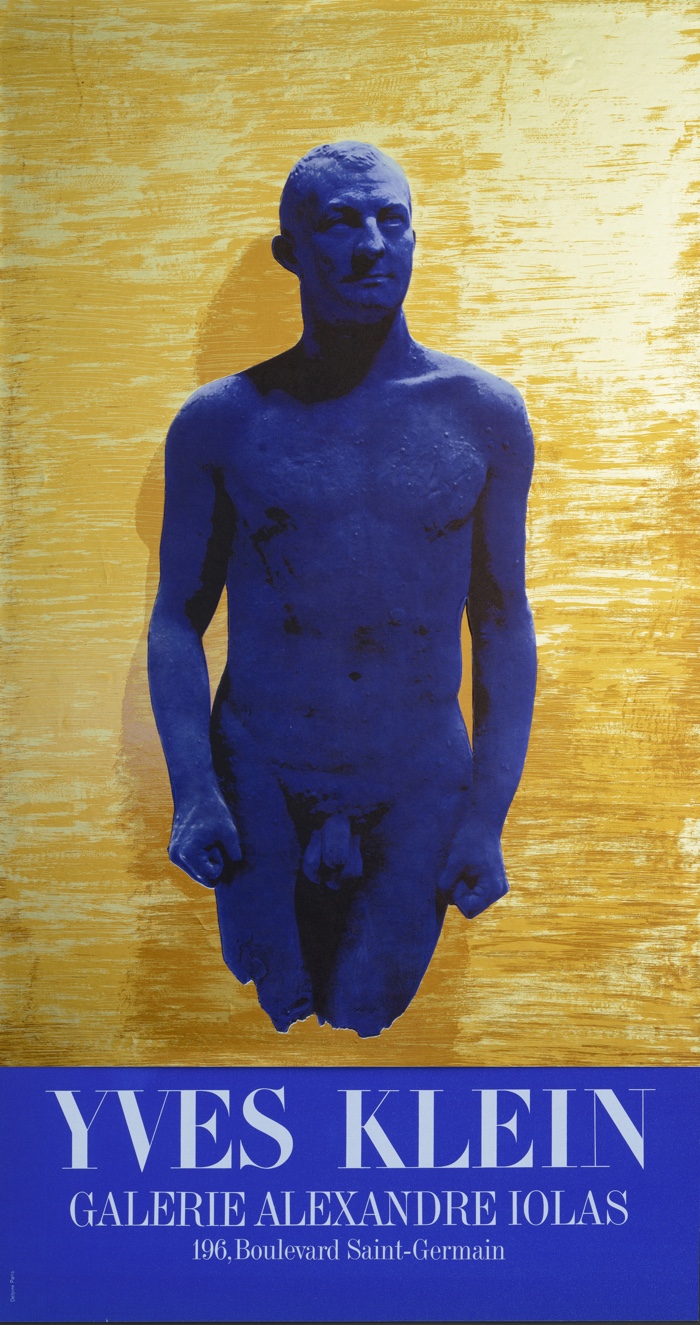

Yves Klein, Anthropometrie in IKB on Monogold, 1965 (exhibition poster), Galerie Alexandre Iolas, Paris. © Yves Klein / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

More views of the exhibition space:

Alchemie. Die Große Kunst/Alchemy. The Great Art (exhibition view.) © Photo: David von Becker for Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Alchemie. Die Große Kunst/Alchemy. The Great Art (exhibition view.) © Photo: David von Becker for Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Alchemie. Die Große Kunst/Alchemy. The Great Art (exhibition view.) © Photo: David von Becker for Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Alchemy. The Great Art, an exhibition curated by Jörg Völlnagel, remains open until Sunday 23 July at Kulturforum in Berlin.

Previously: The Occult, Witchcraft & Magic. An Illustrated History and Artefact: are technology and magical thinking really incompatible?, From swarms of synthetic life forms to neo-alchemy. An interview with Adam Brown.