Future War, by Christopher Coker, Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Publisher Polity writes: Will tomorrow’s wars be dominated by autonomous drones, land robots and warriors wired into a cybernetic network which can read their thoughts? Will war be fought with greater or lesser humanity? Will it be played out in cyberspace and further afield in Low Earth Orbit? Or will it be fought more intensely still in the sprawling cities of the developing world, the grim black holes of social exclusion on our increasingly unequal planet? Will the Great Powers reinvent conflict between themselves or is war destined to become much ‘smaller’ both in terms of its actors and the beliefs for which they will be willing to kill?

In this illuminating new book Christopher Coker takes us on an incredible journey into the future of warfare. Focusing on contemporary trends that are changing the nature and dynamics of armed conflict, he shows how conflict will continue to evolve in ways that are unlikely to render our century any less bloody than the last. With insights from philosophy, cutting-edge scientific research and popular culture, Future War is a compelling and thought-provoking meditation on the shape of war to come.

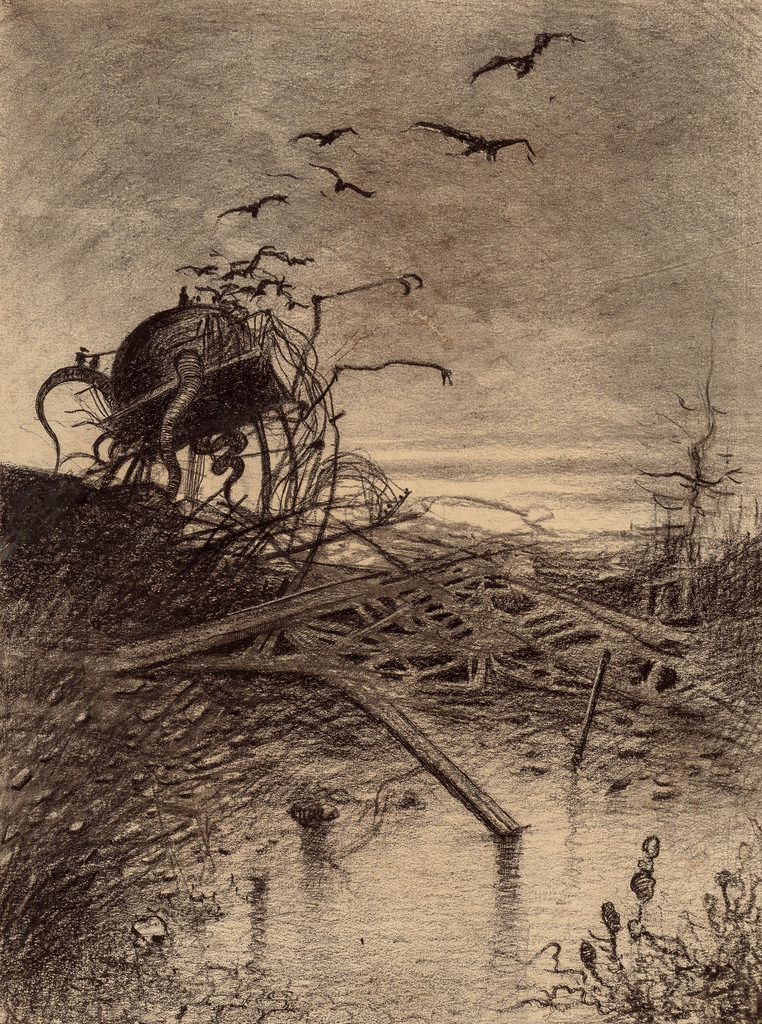

Illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds”

“Peace is an armistice in a war that is continuously going on,” wrote Greek philosopher and historian Thucydides. Coker delves into sociology, psychology, anthropology, history, philosophy, science and literature (in particular science fiction) to remind us that even though battles often rage far away from our own territories, none of us in the Western world can claim to live in peace. Therefore, it would be wise if our societies could develop a critical understanding of war.

The future of war is both fascinating and disheartening. It is made of mood hacking, cloned animals carrying missions as living bombs, false memories implanted in soldiers brains, quantum computing, helmets that turn thoughts into quantifiable information, liquid body armour, etc. Our weapons are many, they are in constant transformation and crucially, they have become ridiculously potent: a single jet bomber, Coker writes, has half a million times the killing capacity of a Roman legion.

But the future of combats might not even be where we expect it to be. There are chances that whole outlook of war will slip away from the usual suspects and battlefields. Wars of the future might no longer be the monopoly of the states but be carried out by new actors that range from big corporations to terrorists or mafias who will attack pipelines, close supply roads or fight for religious, or criminal reasons. Or maybe just one psychopath trillionaire with a grudge against the whole humanity will suffice to wipe us all from the surface of the earth.

Maybe war will look like a competition between machines that handle tactical warfare better than humans. Or maybe the war will be raged in space with lasers that target communication satellites and bring a superpower to its knees, killing no one but sparking catastrophic economic damages (no phone conversations or credit card transaction, mayhem at the stock market and in supermarket supply chain, etc.) Chances are that the battleground might actually be confined to cyber space, a space with its own rules and ethics, with new players, and lack of transparency and accountability.

At some point while reading the book, i almost gave up. It was getting a bit too bleak. Fortunately, Coker is an engaging narrator with a healthy criticism of technological promises. He reminds us that we often fail to grasp the use to which our inventions can be put. Coker illustrates the idea with the plane. Planes were not designed to throw bombs at troupes underneath. In war, they were used for transport and reconnaissance. But in 1911, an Italian pilot flew over Libya on a monoplane and had the idea of tossing over grenades as he approached a Turkish camp. At the time, the world reacted with outrage, it was regarded as a gross violation of the gentlemanly art of war. Quickly enough though, aerial warfare came to play an essential role in strategy.

The ancestor of the flamethrower. Unknown – Codex Skylitzes Matritensis, Bibliteca Nacional de Madrid, Vitr. 26-2, Bild-Nr. 77, f 34 v. b. (taken from Pászthory, p. 31)

On the other hand, inventions that were to change the world didn’t turn out to be such game changers after all. Think of manned spaceflights beyond the Earth orbit. They were much celebrated decades ago but the last mission took place in 1972. Add to the picture the fact that potentially revolutionary inventions sometimes take longer than expected to catch on. Some of the the inventions that changed the face of battles have been conceived long before they were widely adopted. Flame-throwers, for example, first appeared in the 9th Century but were not used much on the battlefield before WWI. As for drones, they first flew at the time of the Vietnam War. Add to that, the unexpected but potentially highly disruptive black swans.

Interestingly, the author also suggests that future ‘may slow down’ at some point. Apparently the cost of circuit fabrication plants doubles every 4 years so the fast-pace innovation we’ve been experiencing over the past few decades might get prohibitively costly.

Cyberdyne Inc. employees wearing Hybrid Assistive Limb, or HAL, robotic suits are seen in 2009. The gear received safety certification Wednesday by a quality assurance organization. Photo AFP-JIJI, via Japan Times

Future War doesn’t deliver easy to digest answers but it stimulates your brain, invites you to questions everything you might read about DARPA megalomania and asks you to consider issues such as our ability to design a conscience into our machines, the cultural impact of conflicts where there’s no human hero to celebrate, the ebbing away of governments power and the rising role taken up by citizens, corporations or future ISIS-like groups in micro and in global conflicts.

But ultimately, what i found most interesting about this book is the way it extend way beyond the military and talks about the future in general and our tendency to be gullible and uncritical regarding the promises of technology. It shows us that the future is incredibly hard to predict and that science fictions writers routinely get it more right than technology developers and other innovation evangelists.