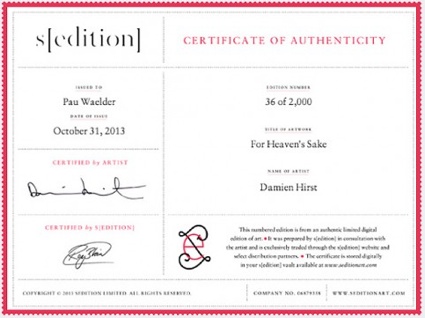

Pau Waelder has recently published at Merkske $8,793 Worth of [Art], a collection of 159 real and false certificates of authenticity, culled from S[edition], an online platform that sells limited edition artworks in digital format. All Waelder had to do was a small ‘hack’. He copied the preview certificates of all artworks being sold in the “curated” section of Sedition. At the time the preview of the certificates displayed his name as owner and a fake edition number, just as if he had bought them. He then added to these certificates real certificates from artworks he bought on the platform. That was it.

Pau Waelder has recently published at Merkske $8,793 Worth of [Art], a collection of 159 real and false certificates of authenticity, culled from S[edition], an online platform that sells limited edition artworks in digital format. All Waelder had to do was a small ‘hack’. He copied the preview certificates of all artworks being sold in the “curated” section of Sedition. At the time the preview of the certificates displayed his name as owner and a fake edition number, just as if he had bought them. He then added to these certificates real certificates from artworks he bought on the platform. That was it.

The title refers to the amount that would have been paid if all of the works had been bought as the certificates apparently attest.

Waelder is not an artist, he is an independent art critic, curator and a researcher in new media art. And judging from what i read in his essays, he is someone who certainly has a few interesting comments to make on notions of ownership and authenticity in the digital era, networked pieces sold and exhibited in gallery environment and “traditional” art sold and exhibited online, new ways of selling art online, “Damien Hirst for six quid”, etc. Someone to follow on twitter and elsewhere. And someone to interview…

Hi Pau! You’re an art critic and curator so i’m tempted to think that $8,793 Worth of [Art] functions also as a piece of art criticism. What motivated the publication of $8,793 Worth of [Art]?

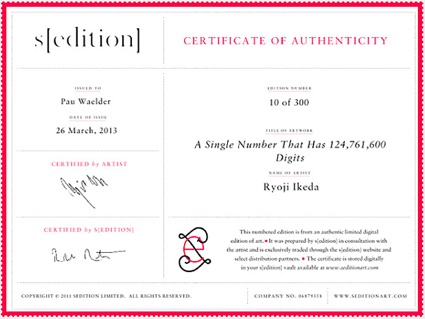

To be honest, I didn’t know if it was worth publishing. I am working on my doctoral research on art, new media and the art market and Sedition is one of my case studies. I’ve followed this platform with great interest since it was launched on November 2011 because I consider that its business model could be a viable way for selling new media art. I’ve also bought some artworks (or editions) in order to experience what it meant to collect these pieces and be able to experience them on my computer, smartphone or tablet. So far, I’ve learned that I really don’t look at the artworks very often, so probably I should have a screen connected to the Internet and hung on a wall at home to really enjoy these works as I do with other artworks I own. Another thing that struck me from the beginning was that the only document asserting my ownership of these “digital editions” was an equally digital certificate of authenticity, which is in fact a JPEG that pops up in my profile page.

One day, as I was browsing Sedition’s website to have an idea of the average price of the artworks, I noticed that on the page of each artwork there was a preview of the certificate of authenticity that I would get if I bought the piece. This preview looked exactly the same as the certificates of the artworks I owned, including the artist’s signature and an edition number. So I started taking screenshots of the preview certificates of all the artworks and kept them in a folder. My intention was (and is) to use this information in my thesis. It was later on that I thought it would be interesting to put together the real and false certificates in the form of a book, which would be an artist’s book if I were an artist. Since I’m not, I didn’t know what to do with it until I contacted Merkske and they decided to publish it. We present it as a limited edition for a low price that is incremented as more copies are sold in order to (playfully) follow the rules of the art market.

In an article you wrote for artnodes, you mention Olia Lialina’s exhibition Miniatures from the Heroic Period, in which she offered for sale 5 works of net art, by Alexei Shulgin, Heath Bunting, JODI, Vuk Ćosić and herself. That happened in 1998. How much has changed since 1998? And why do you think now is a better time to sell art on the internet?

I’d say that one of the changes has taken place in Olia Lialina herself: if you read, for instance, her texts from 1998 (cheap.art), 2007 (Flat against the wall) and 2013 (Opening speech at Offline Art: new2 at XPO gallery), you will see an evolution on her point of view about the delicate question “does it make sense and is it possible to show net art in an art gallery?” As she admits, her answer has changed “from a definite No to Maybe, to Yes, but and finally, to Yes.” I don’t criticize her change of mind, in fact I welcome it as the result of observing this situation for more than a decade. I agree with her in the fact that the web is now a mass medium. The naïeveté that impregnated our perception of this medium is long gone, and therefore it may be argued that a gallery environment is valid for a networked piece since it is placed in a space that invites a more focused observation and finally does not extract the piece from its original context, since the Internet is everywhere now.

Lialina’s remarks are part of a wider context in which many artists have developed innovative ways of selling art online, or making a net art piece salable in the context of a gallery. For instance, Carlo Zanni has been researching on this subject for more than a decade and has created artworks such as Altarboy (a net art piece sold as a server-sculpture in 2003) or My Country is a Living Room (an online generative poem made in 2011 which can be seen on pay-per-view). Mark Napier created The Waiting Room in 2002, an online piece that was sold at bitforms gallery and requires collectors to share the same online space. Rafaël Rozendaal is known for selling his websites under his own Art Website Sales Contract, which he also shares with other artists. And lately Aram Bartholl is developing interesting ways of taking online art to the gallery as in the group show OFFLINE ART: new2, which he curated in 2013 at the XPO gallery in Paris. These are just some examples, but they illustrate the fact that many people have been thinking about selling net art since the late 1990s.

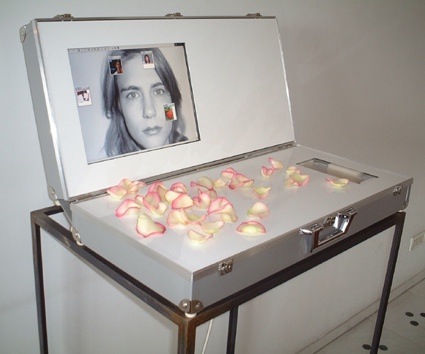

Carlo Zanni, altarboy, 2003

Carlo Zanni, altarboy, 2003

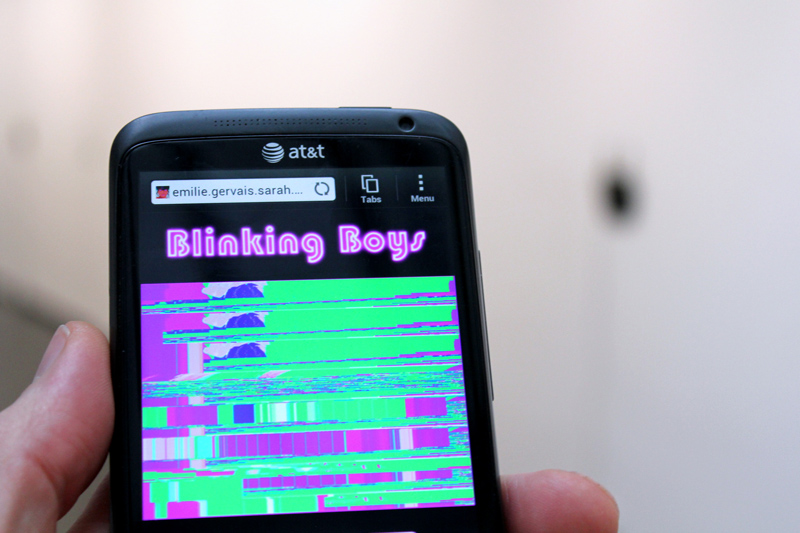

Aram Bartholl, OFFLINE ART: new2 (Emilie Gervais and Sarah Weis, Blinking boys), 2013

In a parallel direction, many other people have been working on selling “traditional” art (paintings, sculptures, drawings and so on) online. Probably the most notable example is Saatchi Online (now Saatchi Art), an online platform where artists can set up a profile and sell their work. It was launched in 2006 and quickly attracted around 70,000 artists who sold their work without paying commissions to Saatchi. It was estimated that the sales amounted to around $130,000,000 in 2007. In 2010, the website was redesigned and now took a 30% commission on each sale. Around a year later, several new platforms where created, such as VIP Art Fair (now Artspace), Artsy, Paddle 8 or Sedition. Maybe the news around Saatchi’s website making so much profit spurred these other initiatives, or maybe as Olia Lialina says we’ve reached a moment in which most people in the art world understand the medium. In any case, it must be pointed out that most of these platforms are not particularly interested in selling new media art, they sell the same artworks that you may find in an art gallery or an art fair, but now they do it online.

Rafael Rozendaal, Hybrid Moment

Rafael Rozendaal, Hybrid Moment

At the time of its launch, enthusiastic journalists repeatedly wrote that sedition was ‘revolutionizing the art market’. But i’ve been wondering whether sedition truly offers something new to the art market – in general and on the internet- or whether it isn’t just replicating ‘traditional’ models of selling artworks, except that everything takes place online. What is you opinion on this?

Sometimes, when I read news on the mainstream media about art and technology I have the impression that the journalist has been hibernating for the last ten years. Obviously, there are many journalists who are quite aware of what is going on, but at the same time it seems that everything was invented yesterday, everything has to be new and revolutionary, as if it were a newly released product from the computer industry. So it is not surprising that Sedition was described in that way. Certainly their model is interesting, but not that new, since other people had been working in this direction. I remember, for instance, Carlo Zanni telling me some years ago that it didn’t make sense to sell a video in a very limited edition at a high price when you could sell it at a more popular price in an edition of several hundred (or thousand). But Sedition has turned these ideas into a working platform and it has done so with good funding and connections in the art world. Certainly, if Sedition hadn’t launched selling “Damien Hirst for six quid” it wouldn’t have attracted the attention of the media, and the model would not seem so revolutionary, since it is in fact quite unprecedented to “own a Damien Hirst” (with a signed certificate of authenticity) for that price. From the point of view of someone who is familiar with net art and new media art in general, it makes no sense to pay any amount for a JPEG of a painting by Damien Hirst. I guess this is true for many people who like Hirst, too. In my opinion, Sedition is interesting when it sells a work by Ryoji Ikeda, Rafaël Rozendaal or Casey Reas, which must be experienced on a screen or a projection anyway. Of course, it is not the original work, which usually results from a continuous calculation process or is interactive. What you get is a video, but for the price you pay it is obvious that you can’t ask for more, so in a way it is similar to buying a lithograph.

Sedition replicates traditional models and it has to do so, because the art market is based on those models. It needs scarcity (limited editions), control over the artworks (a closed system for accessing the files) and certificates of authenticity. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be taken seriously. The problem is therefore not so much with Sedition itself but with the contradiction between how the art market works and what it means to sell, buy and own digital files.

When asked about piracy, the founders of sedition answered: “The videos cannot be streamed to someone who doesn’t own them. As for the still works, they are digitally watermarked and have their owner’s name on them.” So what is the meaning of the certificate of authenticity and more generally of the notion of ownership in a digital context?

When asked about piracy, the founders of sedition answered: “The videos cannot be streamed to someone who doesn’t own them. As for the still works, they are digitally watermarked and have their owner’s name on them.” So what is the meaning of the certificate of authenticity and more generally of the notion of ownership in a digital context?

I have the impression that Sedition is learning by doing, which is the natural thing to do when you explore a new business model. Initially, the videos on the website didn’t have watermarks, but they were added when they realized they could be copied. The previews of the certificates of authenticity have been changed after I did most of the screenshots, now they don’t display the real signature of the artist nor the edition number. In any case, it is always possible to copy a digital file, and therefore the only way to prove one’s ownership is the certificate of authenticity. Most artists and dealers selling art in a digital format will mention the certificate of authenticity when asked what happens if the collector or anyone else makes a copy of the files. When you access an art website by Rafaël Rozendaal, your browser is loading a copy of the file stored in the server, but the artwork belongs to the person mentioned in the source code. I’d say that ownership of a digital file is mainly about having unrestricted access to it (just as it happens when we buy an ebook or an music album in mp3 format) and some document or database record indicating that you’ve paid for it and therefore have the right to access the file, download it, copy it, and so on.

When I interviewed Rory Blain, director of Sedition, at the UNPAINTED art fair in Munich in January, I told him that ownership in Sedition seemed like a fiction to me. He admitted that owning a digital artifact is a “slightly bizarre idea”, but more interestingly he pointed out that what gives collectors a greater reassurance was the possibility to sell their editions in the Trade section, which is Sedition’s secondary market. In the Trade section you actually make money, because the edition you bought has necessarily risen its value: for instance, an artwork by Ryoji Ikeda that was sold for £5 now costs around £70. So it seems that ownership means being able to sell the digital artwork and make a profit.

Mat Collishaw, Burning Flower Digital limited edition © Mat Collishaw

Mat Collishaw, Burning Flower Digital limited edition © Mat Collishaw

Obviously i’m happy that sedition offers new ways for young artists to earn a living. however, in every interview i’ve read about the platform, the founders and journalists insist on the fact that sedition offers a democratization of the art world and that people who would normally not be able to afford a Tracy Emin can finally do so. This reminded me of an interview in which Takashi Murakami explained that he was selling dolls and little objects of his most famous characters Kaikai and Kiki so that everyone can have pieces of the Murakami art experience. But ultimately, i’ve been wondering how different is a limited edition of a digital work on sedition different from the limited edition of a t-shirt or mug with a Hirst skull or other objects sold in museum shops. is this something you’d like to comment on?

The first article I wrote about Sedition was titled “art for the Long Tail”, since what Sedition is doing is addressing the “Long Tail” (as Chris Anderson would put it) of art lovers who are eager to buy a Tracey Emin but can’t afford it. Following Anderson, it seems that there is a lot of money to be made in selling products for smaller amounts to a large number of customers, particularly if no storage or shipping costs are involved. So it could be a profitable market niche, but then the art market is not like other markets. Digital works on Sedition are not so different from a limited edition of a T-shirt, and in fact the prices are quite similar. This can be a problem if you apply the traditional notion of the artwork as something unique and very limited, which cannot possibly be sold in a museum shop. Murakami states that he sells his merchandise because, to him, there is no difference between “high” and “low” art, that this separation does not exist in Japanese culture. If you apply this idea, then it is not a problem that a digital edition is something like a t-shirt or a mug, because it doesn’t replace the original artwork, it just refers to it or derives from it. Then maybe what you must consider is how much of the “Murakami experience” you get, if it is worth your money or not.

Has sedition reacted in any way to your work?

The only reaction I know of is the following tweet: “Yes, we saw this. Clever appropriation art. Like to see how much will sell” (April 30th). It’s interesting that they are concerned (or interested) about the sales of the book, while obviously this project is not about profit (100 copies at £2-3.5 each is not really money). Anyway, I don’t expect them to “react”: this project is not against Sedition but rather intends to sparkle a conversation about how will the art market adapt to the digital environment: will there really be a “revolution” or a “democratization”? Or will everything just stay the same, the same galleries selling the same art on a website?

Thanks Pau!

You can get the book at Merkske, a publisher of original artworks in book form as limited editions of 100, each numbered and signed by the artist. They have a very small but perfectly curated catalogue.