Postcard from The Siege of Sidney Street, the first armed siege to be recorded on film, 1911. Museum-of-London

Mask from the murder case of PC George Gutteridge by Frederick Browne and William Kennedy, 1927. Museum of London

The Crime Museum Uncovered. Trailer

The blockbuster exhibition in London right now is The Crime Museum Uncovered at the Museum of London. I went on a Tuesday early afternoon, it was packed and it was fascinating. First of all, you learn a lot about crime in the capital and that’s as grisly, weird and demoralizing as you can hope for. But you learn just as much about crime-fighting methods and the challenges facing modern policing.

The main exhibition space presents objects and evidence collected from 24 real-life case files. Some of them relate to the capital’s most notorious crimes. From the Great Train Robbery to the Kray twins. Other cases might be less infamous but they earned their place in the show because of the important role they’ve played in the the development of forensics, because they’ve changed the law or because of the impact they had on society.

The cases described date as far back as 1905 and, apart from the section about terrorism, none of them are more recent than 1975 in an attempt to protect the families of the victims.

It is the first time these objects are shown to the public. They are all part of the collection of the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum -aka Scotland Yard’s Black Museum– which holds evidence gathered over more than 140 years of policing.

The Crime Museum was established in the mid-1870s when the Police started to store the belongings of prisoners while they were being detained. Property left unclaimed was soon joined by the items that the Police had seized during their investigations. The collection was used as a teaching tool for newly trained officers and had never been open to the public before.

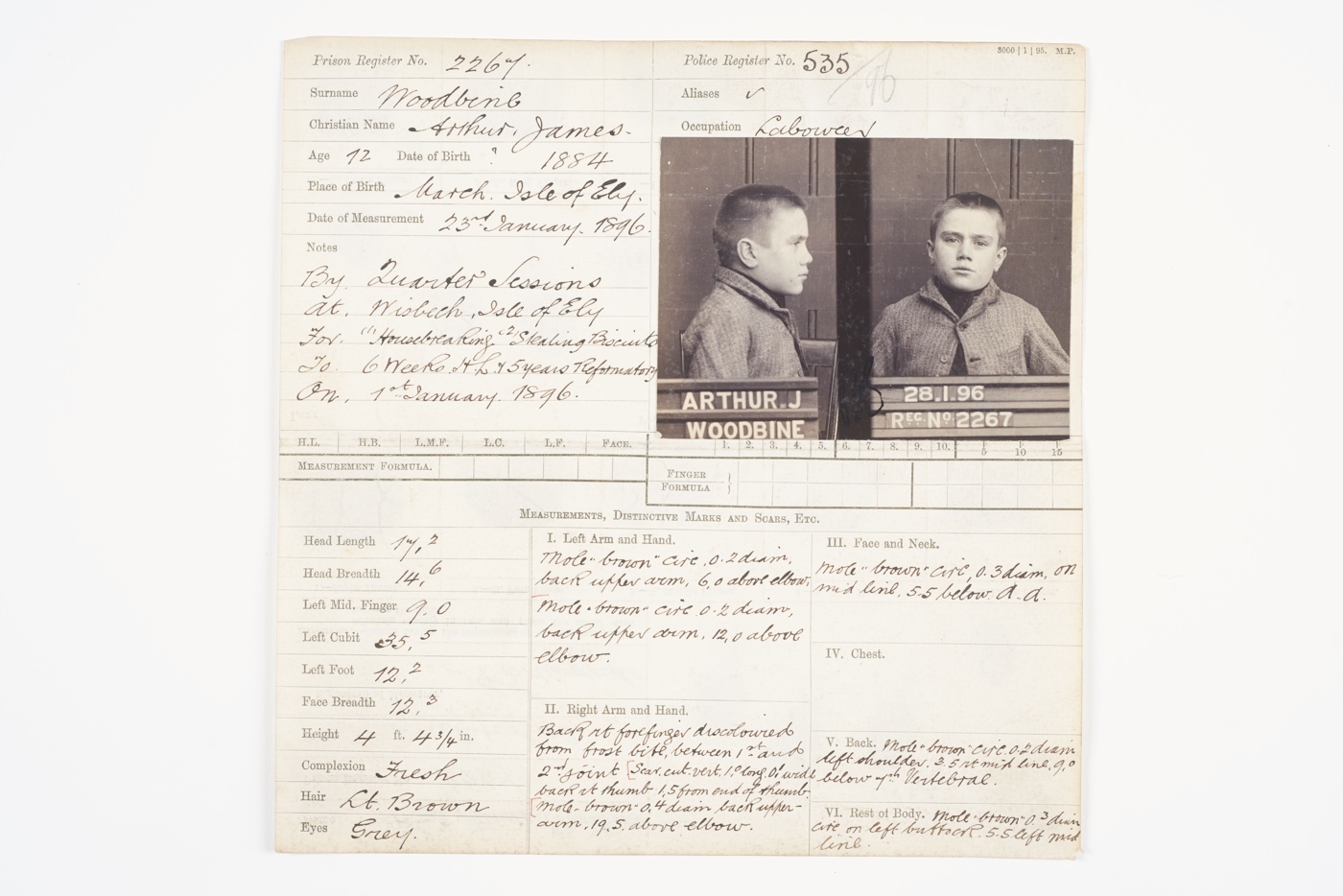

The first section of the exhibition recreates the Crime Museum as it appeared in the illustration of the 1880s and early 1900s, a time when the collection was called the Police Museum. It looks like a Victorian cabinet of curiosities, with its collection of old weapons, shelves of death masks, mugshots with hand-written notes detailing the size of the head of offenders as young as 12 years old, nooses used in hangings, evidence collected during the investigations, courtroom sketches, etc. That and the Jack the Ripper material!

This was the museum then…

Early Police Museum illustration ILN 1883

And this is now:

Inside the Metropolitan Police’s hidden Crime Museum at New Scotland Yard, 2015 © Museum of London

The last part of the exhibition is a video room where experts debate questions that range from “Should such an exhibit be allowed and why?” to “Why does society have such a lurid fascination for crime?”

Now i have a passion for crime stories. Fabricated rather than real ones. This predilection for fiction didn’t prevent me from enjoying the show. I felt that The Crime Museum Uncovered talked more about society, its vices and curiosities, about forensics and history than about the criminals themselves. Something which i think was important to the curators: they wanted to tell horrible stories without ever glamourizing crime and crooks.

What follows is an almost endless accumulation of images related to the show. Some will get a few lines of explanations, others won’t.

I’ll start with a photo i took of the object i found most abominable:

Binoculars, 1945

It’s a bit dispiriting to see how often women are the victims of crimes. I was particularly horrified by this pair of spring-loaded spiked binoculars. A man gave them as a gift to his former fiancée after she left him. They inspired a scene in the 1959 film Horrors of the Black Museum.

Pin-cushion embroidered with human hair by Annie Parker, 1879. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

Annie Parker appeared over 400 times before Greenwich Police Court on charges of drunkenness. She made this small sampler cushion, decorating it with hand-crocheted lace and embroidering it using her own hair instead of thread. She presented it to the prison chaplain who later gave it to the museum. Parker died of consumption in 1885, aged 35. At least two other examples of her work are known to exist.

Masks used by the Stratton Brothers – the first criminals to be convicted in Great Britain for murder based on fingerprint evidence, 1905 © Museum of London

In early April 1905, Alfred and Albert Stratton, two brothers in their early twenties, were arrested for the murder of Thomas and Ann Farrow. At the crime scene, detectives discovered three stocking masks and an empty cash box which had contained the previous week’s takings. At the trial, the most damning evidence was a fingerprint of Alfred’s right thumb found on the cash box.

This was the first criminal case in British history where fingerprint evidence secured a conviction for murder.

The Acid Bath Murderer: Objects relating to the murder of Mrs Olive Durand-Deacon by John Haigh, 1949 © Museum of London

On 18 February 1949, John Haigh shot Olive Durand-Deacon, a wealthy widow, at his workshop in Crawley, Sussex. He removed anything of value and dissolved her body in a drum of sulphuric acid, believing that the police would not be able to convict him of murder without a body. The investigation of the sludge at the workshop by pathologist Keith Simpson revealed three human gallstones and part of Mrs Durand-Deacon’s false teeth which had not dissolved.

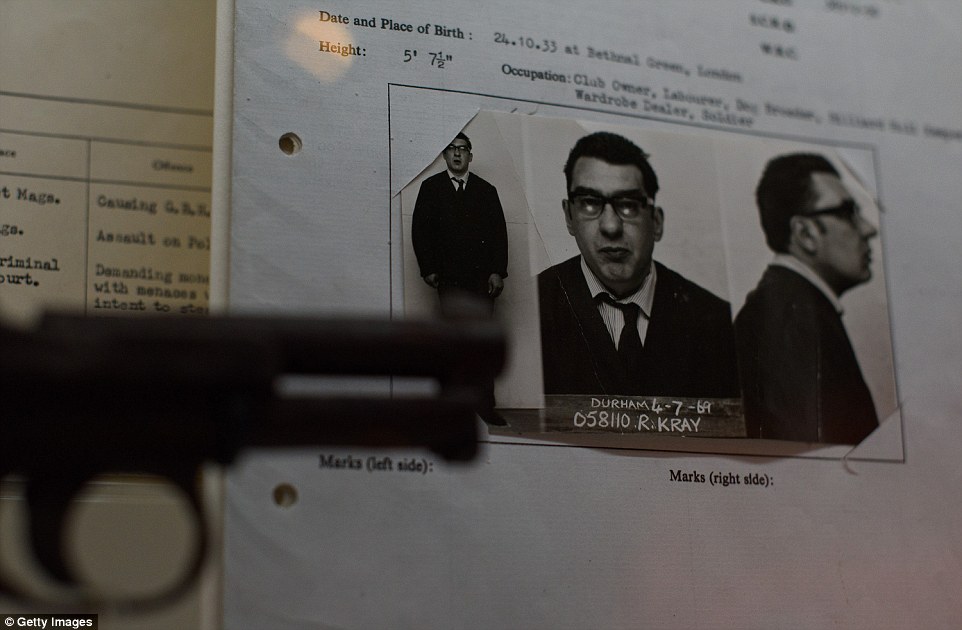

A firearm and criminal record belonging to Ronnie Kray

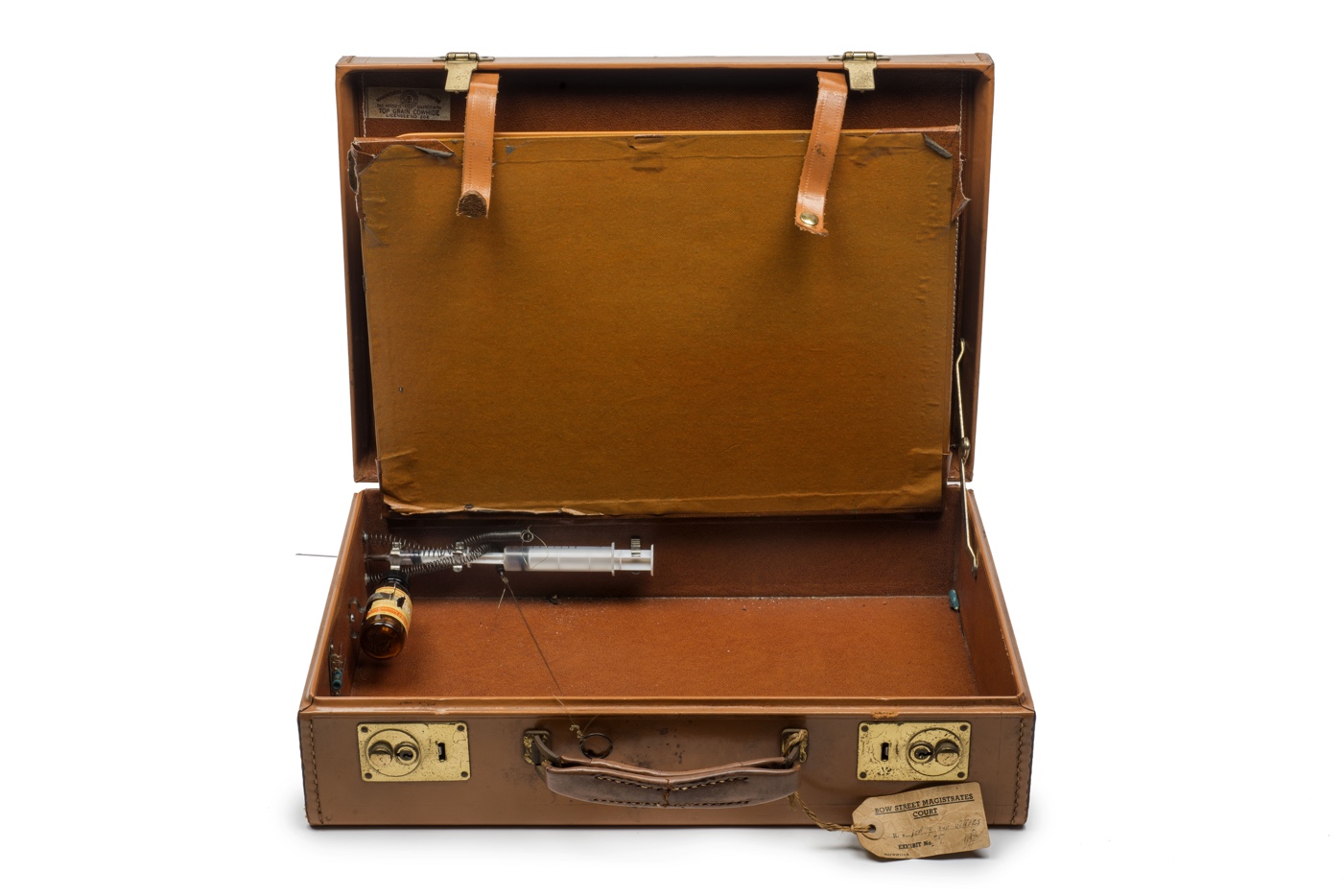

Ronnie and Reggie Kray: Briefcase with syringe and poison intended for use against a witness at the Old Bailey (never used), 1968 © Museum of London

Ronnie and Reggie Kray were twin brothers and gang leaders in 1960’s London. They were responsible for robberies, assaults, protection rackets, fraud and murder. Due to intimidation and witnesses refusing to come forward, they were almost untouchable. However, in 1968 the police arrested Paul Elvey who admitted involvement in a number of attempted murders. Other witnesses started talking. In 1969 the twins were found guilty of the murders of George Cornell in 1966 and Jack ‘the Hat’ McVitie in 1967. They were sentenced to life imprisonment.

On display at the Museum of London is a briefcase hiding a spring-loaded syringe and bottle of hydrogen cyanide that was made to kill a witness about to testify against the Krays, the handgun used by Reggie Kray to try to kill Jack McVitie, the crossbow intended for use against an enemy of the Krays and a scrapbook from the late 1960s containing newspaper cuttings on the case.

The Richardsons Electrical generator used to administer electric shocks by the Richardson gang, 1960s Museum of London

In the 1960s, the Richardson gang were Krays rivals. They had a reputation as some of London’s most sadistic gangsters. They were said to enjoy pulling teeth using pliers, cutting off toes using bolt cutters, and nailing victims to the floor with nails. As for the electric generator, it was allegedly used to give potent shocks to the toes, nipples and genitals of their enemies. If the victim didn’t seem to suffer enough, water would be poured over them, the wired attached and shocks administered again.

Capital Punishment: Execution ropes, 19th and 20th Century © Museum of London

Large crowds would gather to watch public hangings in London, and those who could afford to do so rented rooms overlooking the scene. In 1868 public hangings ended and executions were moved to within the prison walls.

Execution box no. 9 from Wandsworth Prison, which was sent around the Britain to be used as required. Photo AP Photo/Alastair Grant via Seattle Time

The box contains two ropes, allowing the hangman to choose the most appropriate one. To test the rope, a canvas bag was filled with sand to make it the same weight as the condemned person. It was attached to the rope, dropped through the trapdoors and left overnight to stretch it fully before the execution. The straps and buckles were used to restrain the person’s wrists and ankles and the hood to cover their head.

Murder bag: a forensics kit used by detectives attending crime scenes © Museum of London

Balaclava and hat worn by gun-man involved in Spaghetti House Siege in Knightsbridge, 1975. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

In September 1975, three armed and masked men burst into the Knightsbridge Spaghetti House, to steal the week’s takings. The robbery went wrong and the gunmen took the staff hostage in the basement.

The gunmen demanded safe passage to Jamaica. This was refused, but they were given a radio, coffee and cigarettes. As the siege progressed, journalists were asked to demoralise the gunmen by broadcasting reports saying there was no chance that their demands would ever be met. Meanwhile, the police squeezed fibre-optic surveillance equipment through a hole in the cellar to monitor conditions inside. A psychiatrist advised police on the group’s mental state. On the sixth day the gunmen surrendered and hostages were released unharmed.

This was the first time police had used psychological strategies to end a siege, had enlisted the help of the media in this way and used real-time surveillance. It was also the Firearms Wing’s first deployment in a major incident.

Handwritten criminal record card for Arthur James Woodbine, aged 12, 1896. Museum of London

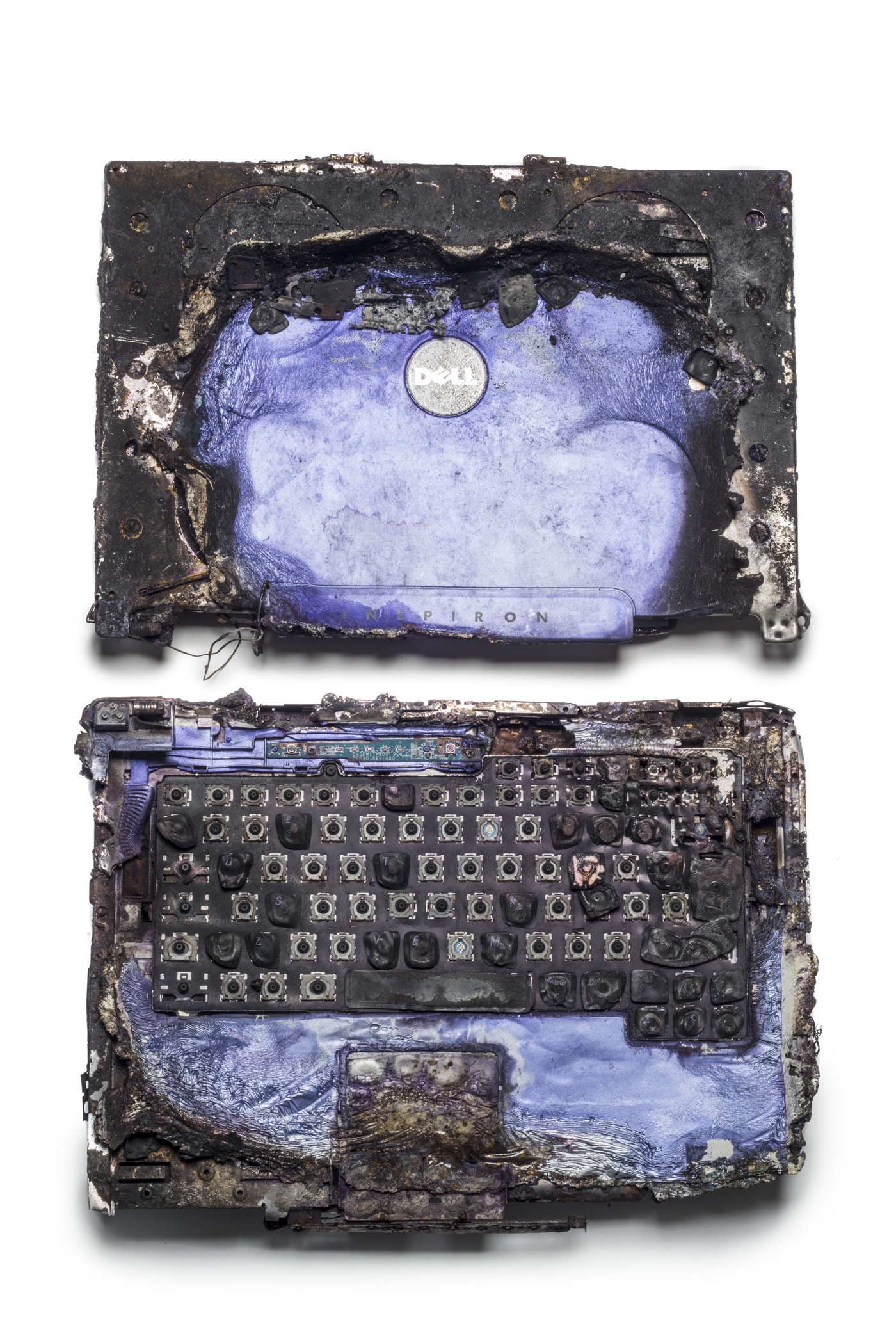

A laptop computer recovered from a car involved in the 2007 Glasgow Airport terrorist attack. Although badly burned, police were able to recover 96% of its data, crucially helping the investigation. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

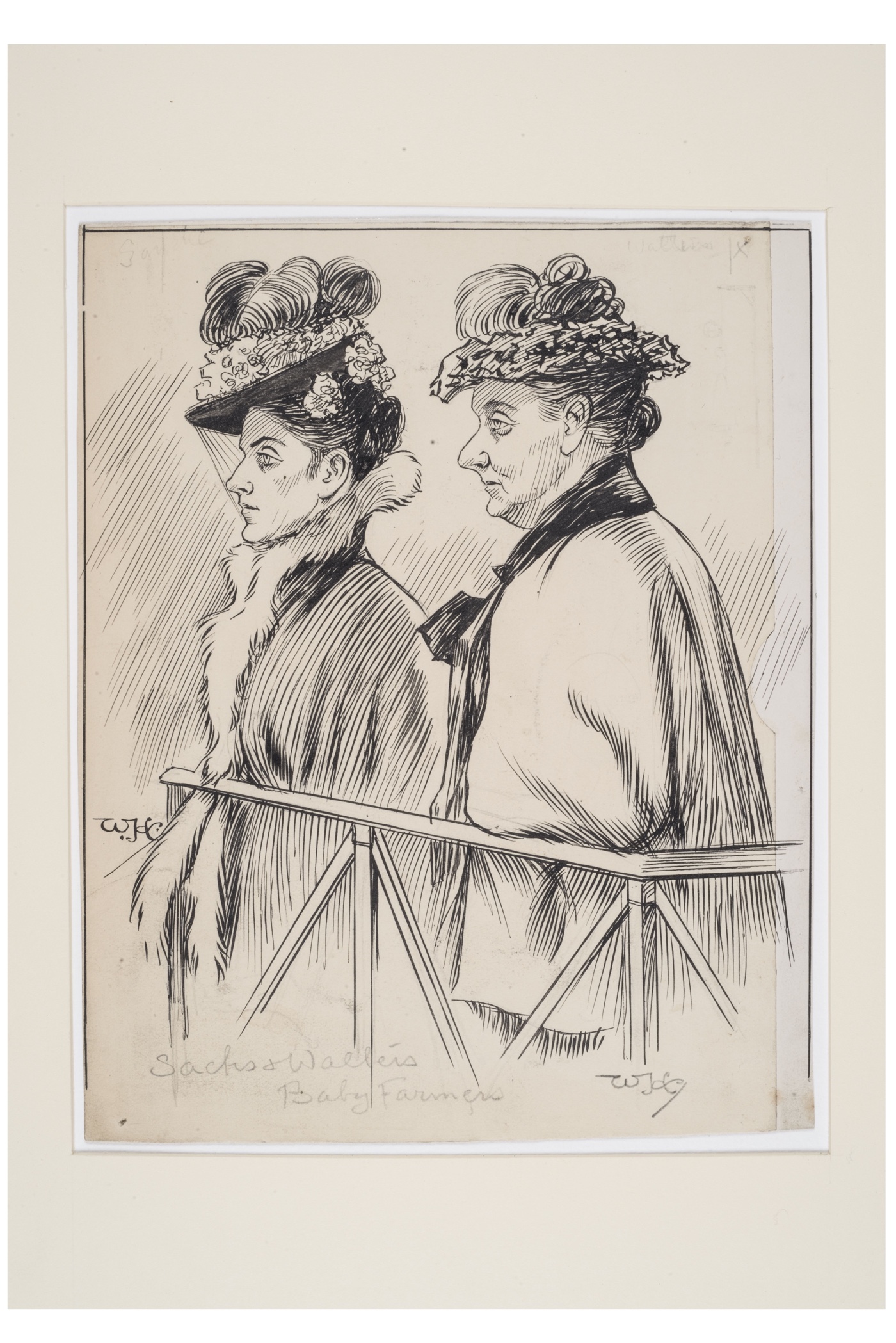

William Hartley Courtroom illustration of Amelia Sachs and Annie Walters on trial for baby farming, 1903. Museum of London

Amelia Sach and Annie Walters, also known as the Finchley baby farmers, were the first two women to be hanged at Holloway Prison.

Legitimate baby farmers provided a service for pregnant unmarried women who were forced to ‘farm’ out their illegitimate child in order to avoid scandal or to keep their jobs. Baby farmers tried to find a family to adopt or foster the child in exchange for a fee. Others like Sach and Walters would abandon or murder the babies and keep the money.

The Smith & Wesson .38 revolver used by Ruth Ellis to murder David Blakely, 1955. Museum of London

Ruth Ellis was London nightclub hostess and the last woman to be executed in the UK, after being convicted of the murder of her lover, David Blakely.

Patrick Mahon Miniature furniture used to reconstruct the murder scene of Emily Kaye, 1924. Museum of London

The butchered remains of Emily Kaye and her unborn foetus were found mostly in a beach house in Sussex (England), which she had shared with her married lover Patrick Mahon. When the police visited the bungalow, they found pieces of boiled flesh in a saucepan; sawn-up chunks of a corpse in a hat box, a trunk and a biscuit tin; and ashes in the fire containing bone fragments. Sir Bernard Spilsbury pieced together the body of the pregnant Emily Kaye, but no head was ever found.

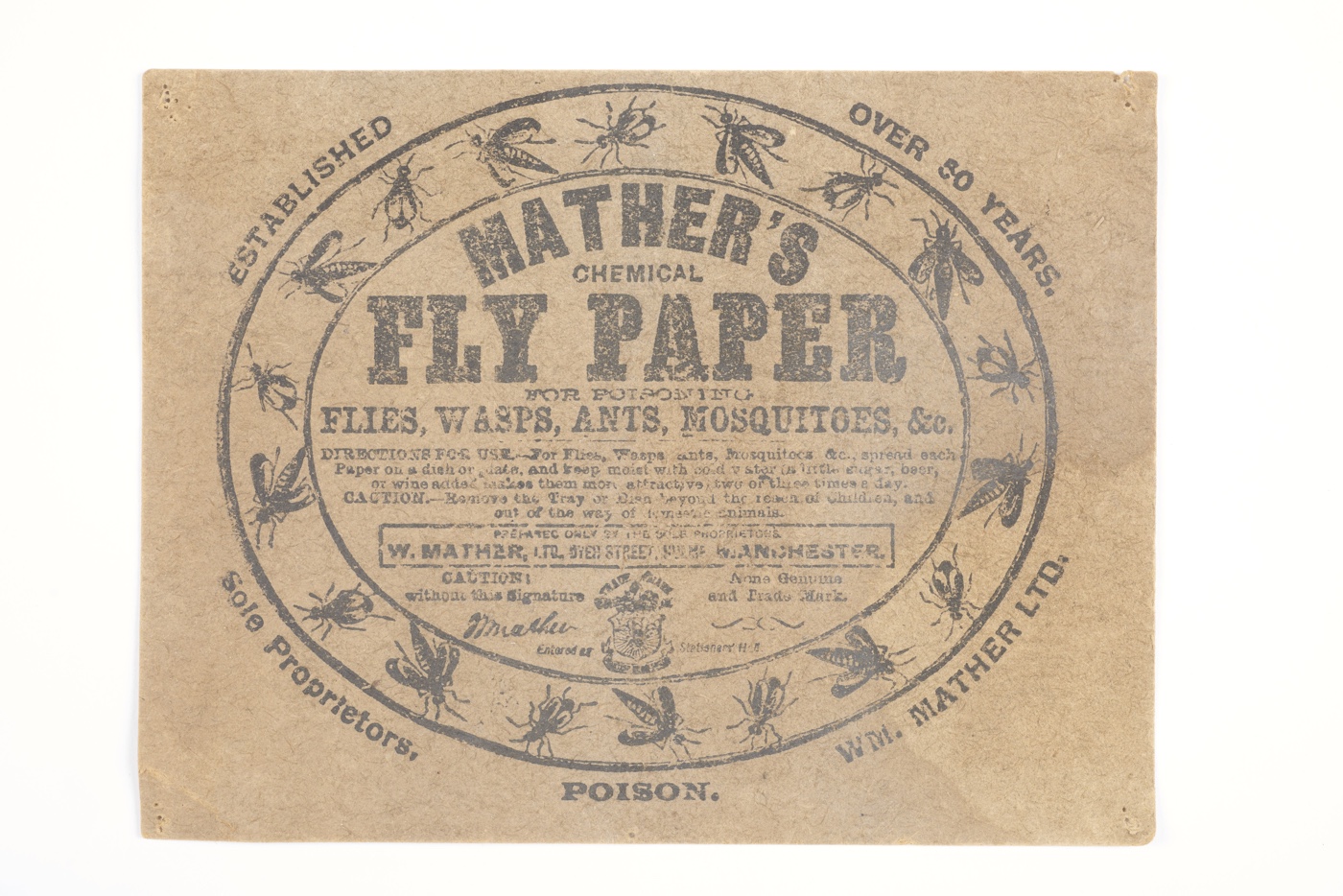

Mathers Arsenical Flypaper, exhibit in the Seddons trial for the poisoning of Eliza Barrow, 1912. Museum of London

The button that was used to convict David Greenwood of murder, 1918. Greenwood was convicted of raping and murdering 16 year old girl, Nellie Trew. This button was found at the crime scene. He denied having met Nellie but was found guilty and sentenced to death, commuted to life imprisonment instead. He was released in 1933 aged 36. But was he guilty of the crime? © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

Death mask of Franz Muller, a German tailor who committed the first British railway murder, 1864. Museum of London

In July 1864, Franz Muller, 24 year-old German tailor living in London attacked Thomas Briggs, 69, in the first-class compartment of a North London railway train. He robbed him, beat him and threw him from the train, committing the first British railway murder. Muller was tracked down through a gold chain he had stolen from Briggs. The case highlighted fears about railway travel and led to the introduction a few years later of the communication cord to stop the train in case of emergency.

Death masks, made from plaster, were created after executions at Newgate Prison. Some were produced for phrenological purposes, to study the shape of a convict’s head, others were made as curios to record the faces of notorious criminals.

Leslie Stone shoe prints recovered by police from murder scene of Ruby Keen, 1937. Museum of London

Violin belonging to cat burglar, Charles Peace, executed for killing a police officer in a burglary gone wrong in 1878. Peace was a musician serenading households by day; returning robber by night. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

Medical implements and drugs used in administering illegal abortions, seized by Metropolitan Police, 20th century. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

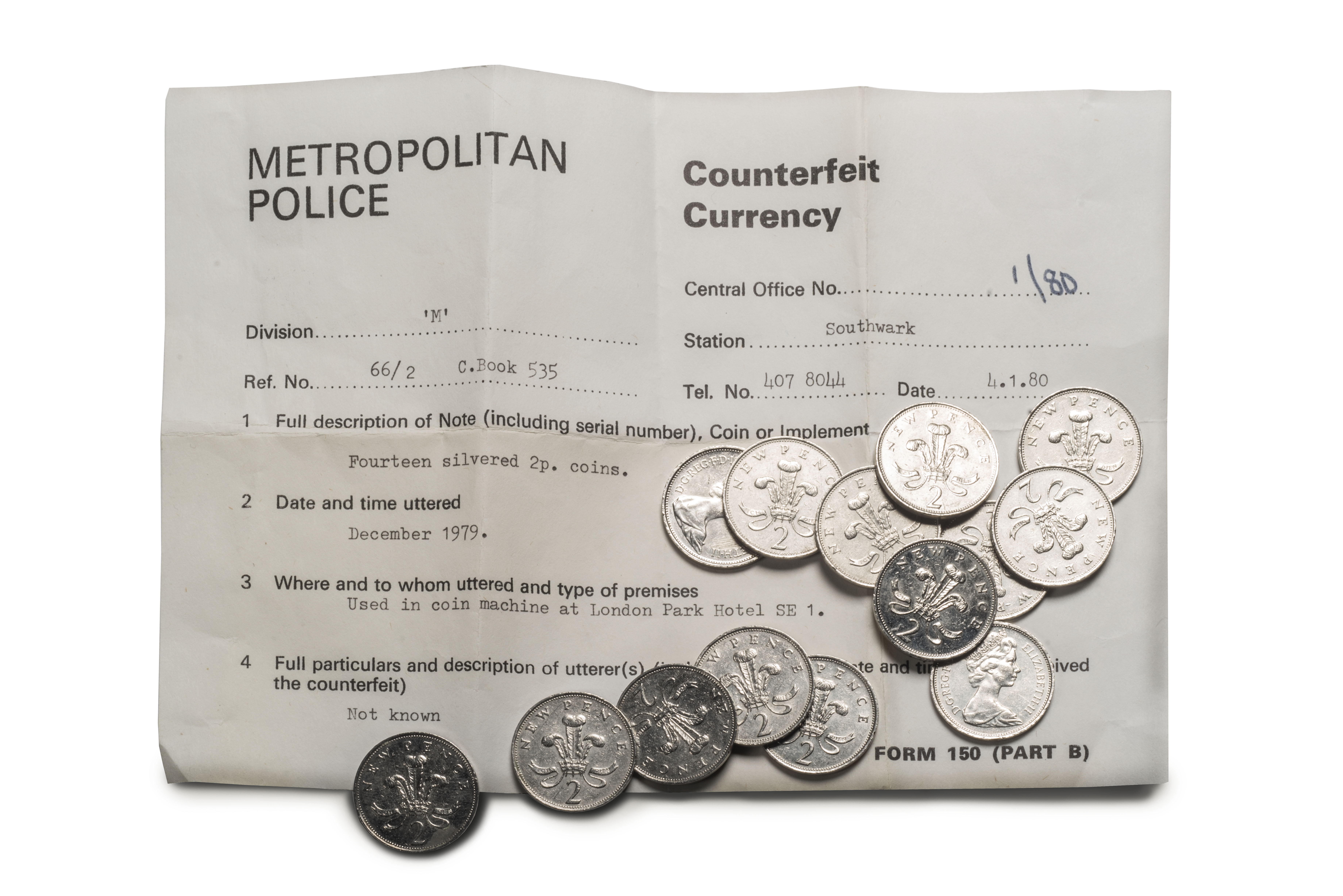

Fourteen counterfeit silvered 2p coins, 1979, recovered by the Metropolitan Police. © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

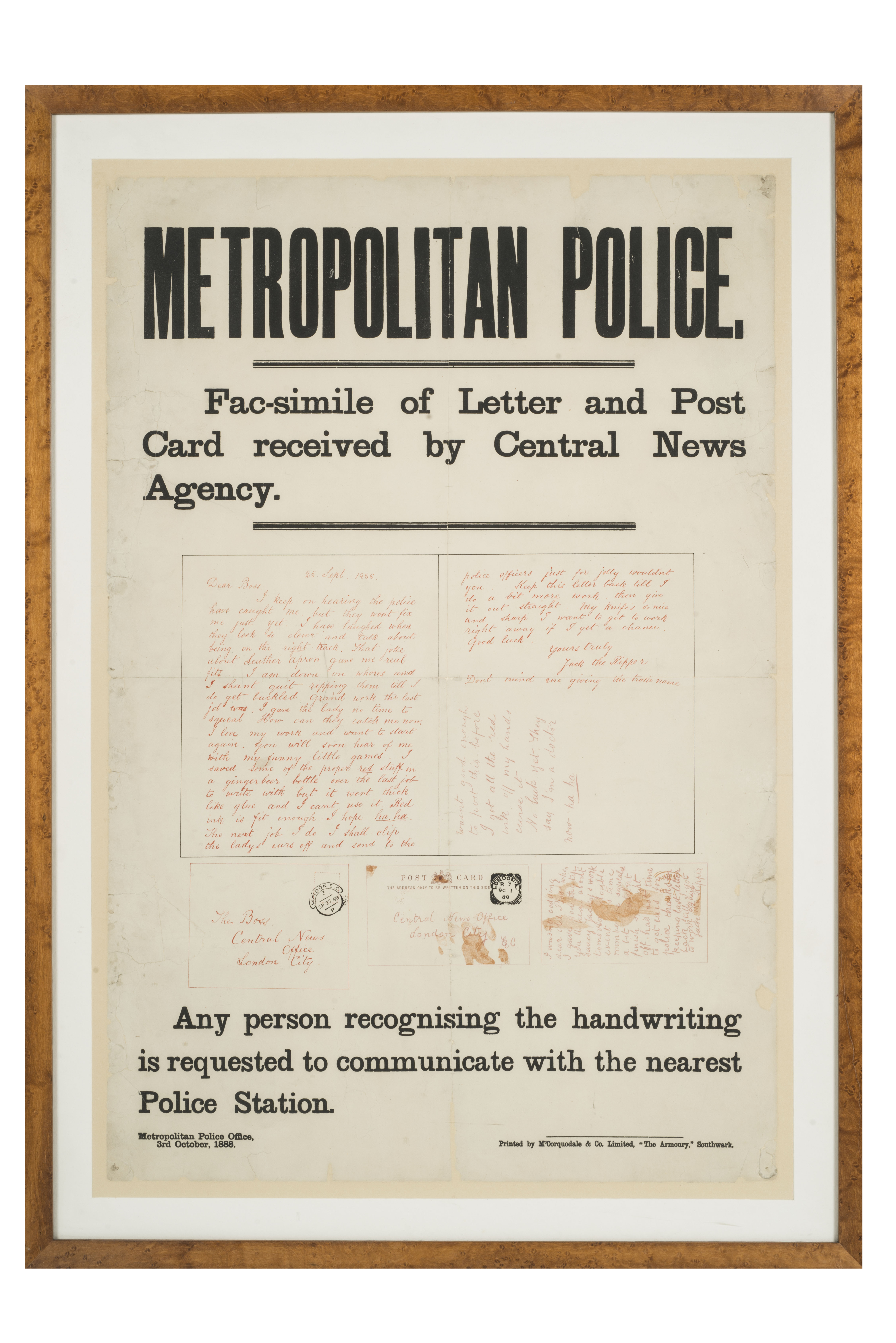

Jack the Ripper appeal for information poster issued by Metropolitan Police, following the ‘Dear Boss’ letter sent to the Central News Agency, 1888. Reads: “Metropolitan Police…Facsimilie of Letter and Post Card received by Central News Agency…Any person recognising the handwriting is requested to communicate with the nearest Police Station.” © Museum of London / object courtesy the Metropolitan Police’s Crime Museum

Between April 1888 and February 1891, eleven women were brutally murdered in the East End of London by an unknown murderer. These murders sparked Britain’s largest ever murder investigation. The Whitechapel murderer became known as Jack the Ripper. He or she has never been identified.

The nickname of this serial killer has its origin in the infamous “Dear Boss” letter, which was sent to the Central News Agency supposedly by the murderer himself on 25 September 1888 and asked anyone recognising the handwriting to contact the police. It was signed “Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

Death mask of murderer Frederick Deeming, a Jack the Ripper suspect, 1892. Museum of London

Medicine case belonging to poisoner and Jack the Ripper suspect Dr Neil Cream, c.1892. Museum of London

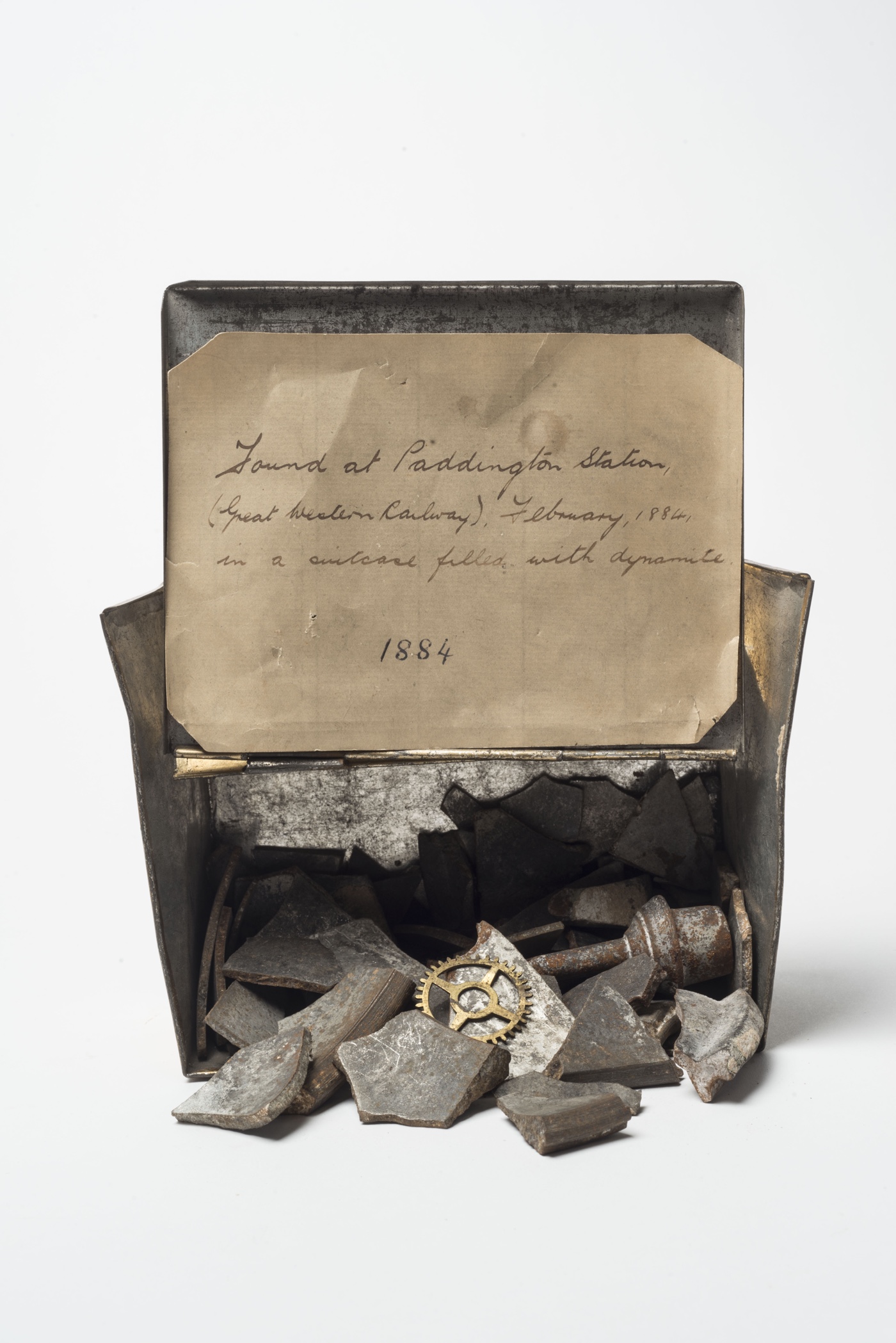

Terrorism: Shrapnel from an unexploded Fenian bomb found at Paddington Station 1884 © Museum of London

Narcotics: Drinks cans used in drug smuggling, seized by Metropolitan Police © Museum of London

Weapons Knuckleduster used in an assault, c. late 19th or early 20th century. Museum of London

Gambling Doctored roulette wheel seized from Barnet Fair, c.1885. Museum of London

View of the exhibition space. Photo Thomas Manss & Company

View of the exhibition space. Photo Thomas Manss & Company

View of the exhibition space. Photo Thomas Manss & Company

View of the exhibition space. Photo Thomas Manss & Company

The Crime Museum Uncovered remains open at the Museum of London until 10 April 2016.