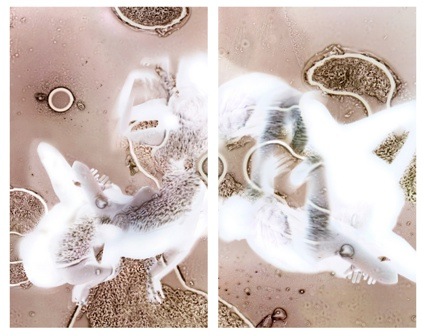

The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama: The Temporary Resurrection and Second Death of Kira, 2011

The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama: The Temporary Resurrection and Second Death of Kira, 2011

Svenja Kratz. Photograph: Dan Cole (via)

Svenja Kratz. Photograph: Dan Cole (via)

This week (or rather semester since i so seldom do proper interview nowadays), I’m talking with Svenja Kratz , an interdisciplinary artist who combines art practice with cell and tissue cultures to investigate the creative and critical dimensions of biotechnologies as well as their impacts on concepts of identity, life, and death.

Svenja has a background in art but she also holds a PhD in Contemporary Art and Biotechnology from Queensland University of Technology and worked at the Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovationin Brisbane, where she completed a PhD in bio-media art.

So far, the artist has worked with media as diverse as fetal calf cells, human blood, maggots, multi-component 3D Human Skin Equivalent (HSE) models or taxidermied insects. She is currently participating to Experimenta Recharge biennial of media art with an ever-changing face mask that uses DNA from Saos-2, a cell line that originally came from the bone cancer lesion of an 11 year old girl who most likely died in 1973 due to the aggressive nature of the cancer. The cells of the little Alice can now be found in science laboratories around the world. Their presence in an art installation highlights the transformative capabilities of Alice’s cells but also the oddity of using living fragments of a human body that died 40 years ago.

The work is called The Contamination of Alice: Instance #8 and since i can’t travel to Melbourne to see it, I thought the next best thing would be to write Svenja and interview her via email:

The Contamination of Alice #8

The Contamination of Alice #8

Transition Piece #2, 2008

Transition Piece #2, 2008

Hi Svenja! Your work Afterlife “looks at the ethical ambiguities and challenges that accompany the use and manipulation of organisms, in particular the use of Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) in cell and tissue culture.” What are those ethical ambiguities and challenges? And how does the work addresses them?

The work Afterlife was a starting point for the development of The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama, a project researched and developed during a three month residency at SymbioticA in 2010. The work developed from my engagement with cells and tissues and particularly the materials that are used in biotechnology such as FBS – a protein rich nutrient supplement used in the media to sustain cells in culture. The serum is derived from the blood of fetal cows. While the idea of draining unborn calves of their blood may sound horrifying, the calves are essentially a bi-product of meat production and while their blood is harvested to produce serum, their bodies are discarded, deemed unfit for consumption.

This work does not aim to demonise the meat industry or the use of FBS, but rather comments that there are victims at every level of consumption, and that the boundaries between good and bad are always blurred. For example, the common practice of slaughtering pregnant cows, and subsequent availability of fetal calf blood, has enabled great advancements in cell and tissue culture and contributed to the development of new medical technologies and treatments for humans and other organisms. This is the same for many cell lines, such the HeLa cell line, isolated from Henrietta Lacks in 1951. Establishment of this, the first human cell line, was a medical breakthrough, contributing significantly to the development of vaccines and scientific research. However, the HeLa line also caused significant distress to the donor family, as the cells were used without the knowledge or consent of Mrs Lacks.

My work aims to draw attention to the often unseen donors or victims of processes of consumption and advancement, but also the shifting boundaries between how we understand life and death. I feel we need to understand that that there are always positives and negatives, and that our technologies and attitudes often reflect current cultural values.

Svenja Johni Kratz, Afterlife. The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama

The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama: The Temporary Resurrection and Second Death of Kira, 2011

The Immortalisation of Kira and Rama: The Temporary Resurrection and Second Death of Kira, 2011

You work with living matter. What are challenges of exhibiting your works? How do you keep them alive for the whole duration of a show for example?

One of the most demanding aspects of working across art and science, and particularly preparing living work for exhibition, are the ethics, biosafety and risk assessments that must be completed to ensure that the work follows ethical guidelines, all risks are minimised and the work is non-hazardous for viewers and installation staff.

Maintaining organisms is also a challenge and relies on careful planning including consulting with scientists, designing the support system and then testing all components to ensure the environmental parameters are appropriate to sustain the organisms for the duration of the exhibition.

You also work with fairly sophisticated technologies. How do you manage to communicate both artistic ideas and scientific innovations that are not that well-known to the public without overwhelming them with complex explanations?

In trying to communicate my ideas, I often focus on storytelling, interweaving scientific concepts with personal experiences and observation, cultural narratives and philosophical ideas. However, this is something I need to continuously work on. When I first started working across art and science, I think I was actually much better at communicating underlying scientific ideas, as my understanding was limited and I was only familiar with lay language. As my knowledge has developed, I sometimes include scientific terms without thinking. Consequently, I often ask my arts colleagues to read my work to ensure the key ideas are clear and understandable, and that I have not included too much superfluous jargon.

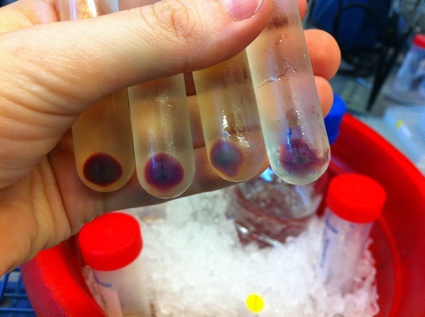

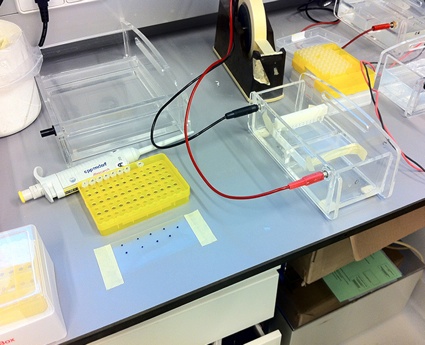

Working in the laboratory

Working in the laboratory

Contamination of Alice #8

Contamination of Alice #8

You are showing Contamination of Alice #8 at the Experimenta Recharge biennial of media art. For this piece you used human DNA to explore the transformative capabilities of cancer cells. Could you explain us what this involves exactly?

The Contamination of Alice, refers collectively to a series of individual works originally inspired by the experience of my Saos-2 cell (bone cancer cell line originally isolated from an 11 year old. girl, Alice) cultures becoming contaminated by a fungus when I was working in the laboratory at IHBI in 2009. While this resulted in the required disposal of the cultures, to minimise the risk of further infection – something that was initially devastating – it really got me thinking about how different organisms take advantage of environmental opportunities, as well as the difficulty of maintaining ongoing containment and control over nature. The loss of the cell cultures also encouraged me to consider the creative potential of the experience and how contamination could be perceived positively as unexpected growth and discovery, rather than something unclean or unwanted. The contamination of the cells was actually a trigger to start exploring microbiology.

The latest instance within the series which was commissioned for Experimenta forms part of this ongoing exploration and connects to Alice’s cells, my lab experiences and notions of becoming, transformation and the interconnections between organism and environment. Through the inclusion of Alice’s DNA (isolated from her cultured cells), the work also starts to engage with genetics and the fact that DNA is not a fixed code, but subject to environmental influence through gene switching. While all Agar faces are made of the same material, the display of the work at a new location will result in different bacterial and fungal colonies, based on the microbes in the new environment.

Transition Piece #3, 2008

Transition Piece #3, 2008

Algernon Becomes a Bird: Maggot Box, 2011

Algernon Becomes a Bird: Maggot Box, 2011

How did you get to work with the Tissue Repair and Regeneration Group at Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation at the Queensland University of Technology?

I started working with the TRR group as part of my PhD research which aimed to explore the creative and critical potentials of cross art-science practice. I was very fortunate in finding a scientific supervisor willing to take me on, train me and fully integrate me into her research group. The support from my supervisor and the entire TRR team enabled me to complete my own lab work and gain first-hand insight into biotechnologies, particularly cell culture and tissue engineering.

Untitled Insects – Detail

Untitled Insects – Detail

Untitled Insects – Installation View

Untitled Insects – Installation View

I read that in 2013 you undertook a 5-month residency at Leiden University and the Art and Genomics Centre in The Netherlands to explore mutagenesis and bioengineering for future energy production. Could you tell us about this research?

Thanks to the Premiere’s 2012 New Media Scholarship from QAG/GOMA, I had the opportunity to complete a six-month residency at Gorlaeus Laboratories at Leiden University in The Netherlands from July to December 2013. The residency formed part of the large-scale Biosolar Cells research programme, which focuses on the potential of solar energy for long term sustainable energy production. While the programme encompasses a variety of research areas, I was integrated into the Solid State NMR group led by Professor Huub de Groot under the supervision of Professor Wim de Grip and PhD candidate Srividya Ganapathy. The project I worked on aims to increase the absorbance spectrum of light powered protein pumps, which are proteins used by Archaea (single-celled microorganisms) to convert sunlight into chemical energy. If successful, the increase in absorbance spectrum enable the proteins to use more of light spectrum to create energy with strong implications for biofuel production. During the residency, I was fortunate to take part in site-specific mutagenesis experiments in which we made highly specific changes to the DNA sequence of the protein in order to induce a shift in absorbance spectrum. I am one of the few artists that can legitimately claim: “I helped make a mutant”.

Why do you think it is important for an artist to get in close contact with science like you do?

I personally have found that working closely with research scientists and engaging with new and emerging biotechnologies has enriched my practice and understanding of biology, new and emerging biotechnologies and the complex ethical issues involved in working with living organisms. Being able to work closely with research scientists has also challenged many of my own assumptions and revealed that artists and scientists, despite governed by different objectives and methodologies, rely on tacit knowledge and understand that discovery is emergent and requires an openness to the unexpected. The combination of art and science is also important as it enables the subjective to enter into scientific discourse and research arenas traditionally dominated by a search for ‘objective truth’. By drawing on, and incorporating, personal experiences, speculative potentials and historical events, the work makes room for multiplicity and can help reveal the way in which knowledge is always situated, provisional, and intimately connected to personal, social, and cultural values.

Working with E.coli bacterial in the laboratory in Leiden

Working with E.coli bacterial in the laboratory in Leiden

What’s next? What are you working on right now?

At the moment I am developing a series of holographic display chambers in collaboration with micro-electronics engineer Michael Maggs, based on my 2013 residency in The Netherlands, that engage with ideas surrounding real and imaginary biotech mutants. I am also working on a series of individual works that operate as thought experiments regarding the idea of genetic legacy, and how, as single woman in my 30s, I might use biotechnologies to ensure my genetic line continues without having children. I am also interested in exploring the emerging field bio-fabrication and am hoping to secure funds to create responsive ‘bio-robots’ using 3D bio-printing techniques. What can I say…the future is exciting!

Thanks Svenja!

Experimenta Recharge, the sixth international biennial of media art, remains open until Saturday 21 February 2015. In Melbourne.