Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

A few days ago, Chris Salter, along with his collaborators Sofian Audry, Marije Baalman, Adam Basanta, Elio Bidinost and Thomas Spier, premiered n-Polytope, Behaviors in Light and Sound after Iannis Xenakis at LABoral Art and Industrial Creation Centre in Gijón, Spain.

The cutting-edge light and sound environment is an homage to Iannis Xenakis‘ Polytopes which at the time of their development (1960s-1970s) were regarded as pioneering and radical. Reading articles about the Polytopes, you realize that many of the concepts and structures used to describe them are part of today’s new media art and interaction design language: large-scale “multimedia performances”, “immersive architectural environments”, etc. Xenakis’ Polytopes were live performances that merged electronic sound, light shows, and temporary structures. They made the indeterminate and chaotic patterns and behavior of natural phenomena experiential through the temporal dynamics of light and the spatial dynamics of sound. But as ground-breaking as they sound, the polytopes are still relatively unknown.

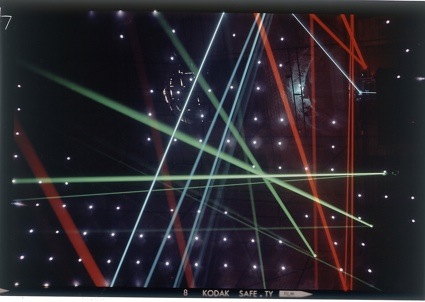

Iannis Xenakis,Polytope de Cluny, Paris, 1972 (photo)

Iannis Xenakis,Polytope de Cluny, Paris, 1972 (photo)

Salter’s n-Polytope re-imagines Xenakis’ work as short performances as well as a continuously evolving installation, both steered through a sensor network utilizing machine learning algorithms. And i’m going to pretty much copy/paste the press release now:

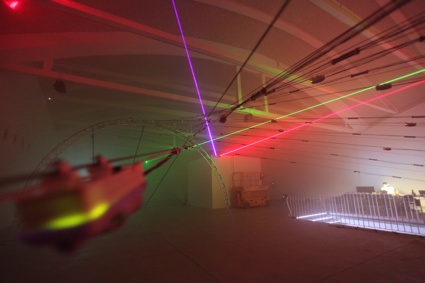

“The ‘learning’ network studies the rhythmic and temporal patterns produced by the light and sound and helps in generating a totalizing, visceral composition that self organizes in time. LED’s and tiny speakers are suspended through the space on a single ruled surface, creating a walk-through performance environment which continually swings between order and disorder, akin to Xenakis’s original fascination with the behaviors of natural systems. Creating bursts of light as well as evolving patterns, the behavior of the LED’s suggest cosmological events, like the explosion of stars and supernovas. While the LED’s create a changing space of bursting points, colored lasers that bounce off the surface of fixed and changing mirrors generate fleeting architectures of lines and shapes that that appear, flicker and disappear before the visitors’ eyes. Counter-pointing the intense visual scenography, multi-channel audio from the small speakers as well as the larger environment fills the space, shifting between sparse natural and dense electronic textures – noisy bursts, clangerous, gamelan-like lines and percussive explosions of sound. Across the architectural structure, the network of tiny speakers produce the behaviors of mass sonic structures made up of many small elements (sonic grains) creating swarms of tiny sounds that resemble a field of cicadas or masses of insects.”

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

Check out this video on El Comercio : Chris Salter briefly explains the work and in the background you can get a sneak peak of the preparation of the installation at LABoral.

I haven’t traveled to LABoral to see the installation/performance but i’m glad the new work gave me an opportunity to briefly interview Chris Salter. Salter is Associate Professor for Design + Computation Arts at Concordia University in Montreal and Director of the Hexagram Concordia Centre for Research-Creation in Media Arts and Technology. The artist and researcher is currently working on Alien Agencies: Ethnographies of Nonhuman Performance. The little information i found about the book sounds as exciting as its title. The publication will explore questions such as What does it mean that nonhuman matter “performs”? How can contemporary techno-scientifically influenced and produced artworks be understood under the term “new materialism” – the increased interest in the acts of nonhuman objects, processes and matter itself promoted by such scholars as Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Karen Barad and Andrew Pickering? What can fields and practices fields such as Science, Technology and Society (STS), anthropology and sociology offer to current technologically molded practices in the area of “research-creation?”

Christopher Salter works on his installation n-Polytope at LABoral. Photo: LABoral/Sergio Redruello

Christopher Salter works on his installation n-Polytope at LABoral. Photo: LABoral/Sergio Redruello

Hi Chris! Unfortunately i couldn’t come and see the work in Gijón but i’ve been wondering what visitors can experience exactly during the performance? And since the piece is using machine learning algorithms, does the performance evolve over time and how?

This is a complex question but in a nutshell, what audiences experience is a kind of visceral journey from tranquility to chaos and back again, made manifest through light and sound that is partially choreographed (that is, organized and scored) and partially open to what happens in the environment. The techniques we are using (designed by my collaborator/student Québec based artist and PhD researcher Sofian Audry) come from a branch of machine learning called reinforcement learning – which basically involves software learning agents that interact with their environment in order to achieve a goal. The agent seeks to achieve its goal despite the fact that there is a high degree of uncertainty about the environment – in other words, the agent doesn’t know until it does something and is then “rewarded” in either a positive or negative manner. Hence the term “reinforcement.” The agent’s actions thus influence not only the state of the environment in the present but also can affect the environment’s state in the future.

In n-Polytope, the agent receives sensor-actuator information from the environment (the brightness of an LED or the amplitude of a sound, for example) and can either turn the LED or the sound on or off, receiving a reward for it. However, the environment around the agent (and the sensor) is continually changing, so it’s hard to determine what steps the agent will take and what they will result in. In this sense, the performance is evolutionary in that each “time step” the agent takes is going to be different from the last.

On the opening day, we already had visitors who saw a performance earlier in the day and then one later tell us that they felt the performance was qualitatively somehow different – that it “felt” different. At the same time we have to “tame the algorithms” by shaping how these behaviors and actions are revealed to the public, particularly given that some of these processes take many minutes to unfold and are not entirely interesting in the long run. Sure, they produce patterns but patterns or the formal processes that produce them are not always intrinsically interesting from an aesthetic or affective point of view in and of themselves. This gets us to your next question…

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

The composition “self organizes in time”. Does that mean that the work is going to surprise you? To create light and sound compositions that you had not forecast?

And if that is the case, do you find it upsetting that you have to relinquish some of the control over the system?

The idea that something will surprise you is at the heart of the concept of “experiment.” In science, of course, you want to somehow stabilize this over time and reduce the surprise so things can become consistent and deterministic (and thus, other people can repeat the experiment, achieve the same results and then eventually call this a scientific “fact”). In art, particularly art that utilizes these unstable computational systems, you hope to create the conditions to enable something surprising to happen and then hope it does! This is one reason why artists like Cage with his “chance operations,” Xenakis with his “stochastic music” (i.e., music based on probability models) or us with these statistical procedures from machine learning (which are also similarly stochastic), are interested in using techniques in which the results can only partially be predicted.

The issue of relinquishing control is a really interesting question and I’ve found after working over many years with similar ideas that one is always in a moving target between something which is scripted/fixed and, at the same time, allows a certain degree of improvisation and self-organization in order to keep the sense of “liveness” – that is, something that is taking place right then and there in real time before you. This is the reason to explore these techniques – because ultimately you want to create an experience that renews itself and that maintains its “nowness” – its “life.” Control in the real time context of performance is something that I think is vastly overrated! Despite using computational systems (which are at their heart, control systems) and techniques from probability, for example, Xenakis (or Cage, for that matter) was wholly in control of his work and we are too – in the sense that control involves plotting something out in time in some kind of purposive manner. But at the same time, you are never wholly in control because you are dependent on so many other factors, materials and things that have their own tendencies and predilections — what my friend, the famous sociologist of science Andrew Pickering usefully terms, their “material agency” – their own way of producing material affects in the world.

Detail of the structure of the installation. Photo: LABoral/Sergio Redruello

Detail of the structure of the installation. Photo: LABoral/Sergio Redruello

The installation n-Polytope, tested by Chis Salter and his collaborators during his Production Residency at LABoral Photos: Courtesy of the artist

The installation n-Polytope, tested by Chis Salter and his collaborators during his Production Residency at LABoral Photos: Courtesy of the artist

The installation n-Polytope, tested by Chis Salter and his collaborators during his Production Residency at LABoral Photos: Courtesy of the artist

The installation n-Polytope, tested by Chis Salter and his collaborators during his Production Residency at LABoral Photos: Courtesy of the artist

n-Polytope is using sophisticated technologies that didn’t exist at the time of Xenakis’ experiments, but apart from the technology what does your work bring that sets it apart from his “Polytopes”?

I think there is more that unites our different approaches than separates them, although clearly our own histories are very, very different than Xenakis’s World War II experience. First, the similarities. The original idea to revisit the Polytopes came from two different directions.

The first is my general interest in the history of performative, technologically augmented “total works of art” I wrote a whole book published by MIT Press called Entangled that came out in 2010 about these performative histories) of which the Polytopes are an essential but unfortunately, mostly forgotten part. Indeed, in describing them Xenakis used terms like “interactive,” “self-organizing,” temporal acts, etc. that are part of our cultural vocabulary now.

The second is more specific to Xenakis’ and my own interest in using formal systems (such as those from mathematics or statistics) to generate visceral, perceptual experiences for audiences that continuously slide from order to disorder and in this process, somehow manage to transcend these formal, abstract structures. What is different is clearly the historical and techno-social context that has radically changed since the Polytope de Montreal in 1967. The kinds of media environments that Xenakis had imagined that the Polytopes represent have become, in some ways, common and part of our own technical-cultural moment. Even though we are using very sophisticated techniques culled from current research in computer science and engineering, I think we bring to this re-imagining perhaps a more sober, less utopian approach to technology. Our approach is far less “Platonic” than Xenakis’s in that we are interested less in creating a kind of ideal, perfect experience that would be achieved by the “beauty of numbers” or formal principles of geometric thinking but rather creating something less perfect: more fragmented, disordered and messy and whose actions and influence are open to the world.

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

I’m also quite curious about the fact that n-Polytope is described as a “performance installation”. Could you describe what makes the work performative? Why is it not a simple light show?

There are two scales of performance going on in the piece. First, there is, in the traditional sense of a performance, an event that takes place over a very specific window of time, that has a clear beginning, middle and end and has a specific dramaturgical or narrative shape – that takes the audience through a carefully shaped range of experiences – from a kind of meditative silence to absolute, almost apocalyptic chaos and then back to silence. We run five of these performances daily so people know what to expect – when you use the word performance, audiences understand that they should come in at a specific time and stay the duration and that if they wander in or out they will miss part of the experience. It is, of course, always difficult to create this kind of time in the context of museums or visual art exhibitions (think of works from James Turrell or Robert Irwin which, in one way or the other, force audiences into understanding/experiencing a different sense of time than one is used to in the shopping center/ browsing atmosphere of museums) so we are very clear that one should experience the work from beginning to end.

But there is also a second sense of performance. Indeed, why couldn’t a light show be seen as performative? Why does a performance have to imply a human performer at all?

This is the core question underlying my current book project for MIT Press called Alien Agency: Ethnographies of Nonhuman Performance. There is now a huge interest in science studies, in sociology and clearly in art and design in moving away from understanding performance as something that is a strictly human act and instead, emphasizes material actions or behaviors of techno-scientifically orchestrated things, transient objects and processes. We already see this taking place in the early days of cybernetics and indeed, this is one reason why we subtitle n-Polytope “behaviors” in light and sound. What one should observe and experience is how light and sound acts and unfolds indeterminately over time, that is, performs – particularly given the fact that this performance is not completely under human control but instead, based on the environment.

Image courtesy LABoral

Image courtesy LABoral

Xenakis worked on several “polytopes”. How about you? Do you think that this is the first of many n-Polytope?

I think so. The Polytope LABoral is site specific in the sense that it is built for that particular, difficult space, particularly the acoustic design. As soon as the piece opened, I already started thinking of how we can change it to make it better and to resolve things that aren’t working yet to our satisfaction. There is already interest from other venues in Europe, in Asia and in North America and they will have their own cultural contexts. So, yes, I think there will be other Polytopes to follow!

Thanks Chris!

n-Polytope, Behaviors in Light and Sound after Iannis Xenakis remains on view at LABoral until 10 September 2012.