Last panel, last post about the Drones event organized by the Disruption Lab Network in Berlin a couple of weeks ago.

Compared to my previous post (Eyes from a distance. Personal encounters with military drones), the talks from the panel Tracking Drones, Reporting Lives zoomed out from the personal perspective and brought together a data journalist, a documentary director and an artist whose work examines the drone issue:

Missiles being loaded onto a military Reaper drone in Afghanistan. Image BIJ

Missiles being loaded onto a military Reaper drone in Afghanistan. Image BIJ

From left to right: Tatiana Bazzichelli, Marc Garrett, Jack Serle, Tonje Hessen Schei and Dave Young

From left to right: Tatiana Bazzichelli, Marc Garrett, Jack Serle, Tonje Hessen Schei and Dave Young

Data journalist Jack Serle, who works at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London, as part of the Covert Drone War research team, is involved in the Naming the Dead project which attempts to reveal the names of the civilians and militants killed by the drones in Pakistan since 2004. Film director Tonje Hessen Schei is currently showing in theaters across the world DRONE, a documentary that focuses on the CIA drone war. Artist, musician and researcher Dave Young presented The Reposition Matrix, a workshop series that investigated the military-industrial production and use of military drones through collaborative open-source intelligence and cartographic processes.

The panel was moderated by Marc Garrett, director and founder (together with Ruth Catlow) of the community and art space Furtherfield. In his intro to the panel, Garrett reminded the audience of the role that artists have played in exploring the dark sides of drones, sometimes even anticipating their power as the video BIT Plane demonstrates. In this work (shown at the Furtherfield exhibition Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! two years ago), Natalie Jeremijenko and Kate Rich from the Bureau of Inverse Technology operate a radio-controlled model airplane over the Silicon Valley. By filming the aerial views, the BIT Plane can be seen as a precursor to the emerging DIY surveillance video enabled by the new availability of drones.

Bureau of Inverse Technology, BIT Plane

Another project mentioned by Garrett in his intro to the panel: Joseph DeLappe, The 1,000 Drones – A Participatory Memorial, 2014

Another project mentioned by Garrett in his intro to the panel: Joseph DeLappe, The 1,000 Drones – A Participatory Memorial, 2014

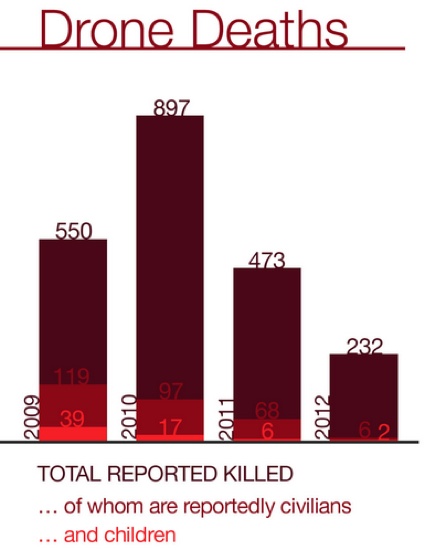

The talk of the first panelist, Jack Serle, focused on the BIJ’s Covert Drone War, a research aimed at providing a full dataset of all known US drone attacks in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen.

When the investigation started, there was online one version of drone attacks and it was coming from Washington. Their official line was that drones were surgically precise and that they were so efficient that no civilians were killed in the strikes:

It’s this surgical precision, the ability, with laser-like focus, to eliminate the cancerous tumor called an al-Qaida terrorist while limiting damage to the tissue around it, that makes this counterterrorism tool so essential.

But the data coming from Pakistan quickly demonstrated that the reality was otherwise.

From The Reaper Presidency: Obama’s 300th drone strike in Pakistan, December 3, 2012

From The Reaper Presidency: Obama’s 300th drone strike in Pakistan, December 3, 2012

BIJ’s work is based on open source data such as media reports, NGO reports, court documents, information leaked by governmental sources, accounts from eyewitnesses, etc. The observation of this data enables also the BIJ to pick out patterns revealing some uncomfortable facts about the war on terror.

For example the BIJ noticed that sometimes a strike would hit a building in Pakistan and that another strike would be launched on the same building 20 to 40 minutes later. The same pattern was observed elsewhere. It reveals that when the CIA was hitting a building, they were in fact waiting for the rescue team (made of both civilians and militants) to come and pick up people who had been injured in the strike. This is obviously a very bloody tactic.

Another pattern observed involved strikes hitting funerals. The CIA exploit a local custom: local commanders often attend a man’s funeral. But of course the people who take part in the funeral and were injured or killed by the drones are not necessarily militants. Many of them are civilians.

There’s more details about these two practices in Chris Woods and Christina Lamb’s article CIA tactics in Pakistan include targeting rescuers and funerals.

By gathering numbers, names and other evidences, the Naming the Dead project counters secrecy and anonymity. Concealing as much as possible is a key element of the drone program, it enables it to continue its activities unquestioned.

Serle explained that with the Drone War Project, the BIJ doesn’t want to morally judge the technology per se. Instead the work of the team aims to bring transparency and enable people to make changes.

The funeral of Akram Shah, a government employee, killed with at least four other locals, all civilians, in June 2011. Image THIS KHAN/AFP/Getty Images, via BIJ

The funeral of Akram Shah, a government employee, killed with at least four other locals, all civilians, in June 2011. Image THIS KHAN/AFP/Getty Images, via BIJ

A Pakistani tribesman sifts through the rubble of his house after an attack in January 2006. Photo: Tariq Mahmood/AFP/Getty Images, via BIJ

A Pakistani tribesman sifts through the rubble of his house after an attack in January 2006. Photo: Tariq Mahmood/AFP/Getty Images, via BIJ

Next in the panel was Tonje Hessen Schei, the director of DRONE which was screened later in the evening (and which i’d recommend you see.)

The film looks at drone under different angles: the families of Pakistani victims of drones, the human rights advocates and activists, the drone pilots (namely Brandon Bryan) and the vast and incredibly lucrative industry which interests lay in keeping this war going on forever and ever.

The director talked about the relationships between the entertainment industry and the military, her disappointment at Obama who had promised to close Guantanamo Bay and who’s now sending drones to kill people, etc.

One of her main concerns regards Europe which knows what is happening and remains silent. The United States is setting a worrying new standard of warfare with the drone program and it’s only a question of time before we see Russia, Iran, China and other countries use drones to go after anyone they regard as a threat to their country. When that time has come, how will we be able to counter it? How are we going to say that the practice is illegal when we’ve done nothing to stop the United States?

Drones have changed warfare and its future. They’ve become the new normal even though there has never been any proper debate about the ethical, moral and legal challenges they present.

A survey found that 66% of the U.S. people is in favor of drone strikes. Perhaps the percentage would me much lower if people were actually presented with all the facts. There has been a wide media coverage of the DRONE documentary in both the UK and Norway but the film is still very much under the radar in the U.S.

The trailer of the documentary is very catchy and spectacular. It’s part of the strategy of the film director who wanted to relate to mass culture and appeal to the broadest audience possible.

DRONE, the trailer

Image from the documentary DRONE. Google Earth

Image from the documentary DRONE. Google Earth

Image from the documentary DRONE. Photographer: Lucian Muntean Copyright @ Flimmer Film 2014. All rights reserved

Image from the documentary DRONE. Photographer: Lucian Muntean Copyright @ Flimmer Film 2014. All rights reserved

Image from the documentary DRONE. Archive Footage

Image from the documentary DRONE. Archive Footage

Image from the documentary DRONE. Photographer: Noor Behram Copyright @ Flimmer Film 2014. All rights reserved

The last speaker in the panel was artist Dave Young who made a series of valid points:

– The war on terror operate often in deserts. This is what Deleuze calls a ‘smooth space‘, a surface that can be interrupted, moved and reconfigured without leaving any trace.

– Young also talked about The Reposition Matrix, a series of workshops dedicated the use of cybernetic military systems such as drones and the Disposition Matrix, a dynamic database of intelligence that produces kill-lists for the US Department of Defense. Working together, workshop participants developed a ‘cartography of control’: a map of the organisations, locations, and trading networks that play a role in the production of military drone technologies. The artist explained how some of the information used in the workshop came from unexpected sources: such as google satellite maps where sometimes the shadow of a drone would appear on a view or facebook where many soldiers post photos of their life. So in the background of selfies or group portraits, one can glimpse the base where they are working.

– During World War II, Norman Wiener worked on a research project at MIT on the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns and guided missile technology. He studied how a missile changed its flight path through the use of advanced electronics. What intrigued him was the principle of feedback that was used, i.e. the missile gave feedback regarding its position and flight path towards its target. It then received instructions for small adjustments to its flight path in order to further stabilize it and to arrive at its target, etc. (via) His research was abandoned after the war but the concept of continuous feedback between the missile system and its environment can actually be extended to other systems and this eventually led him to formulate cybernetics.

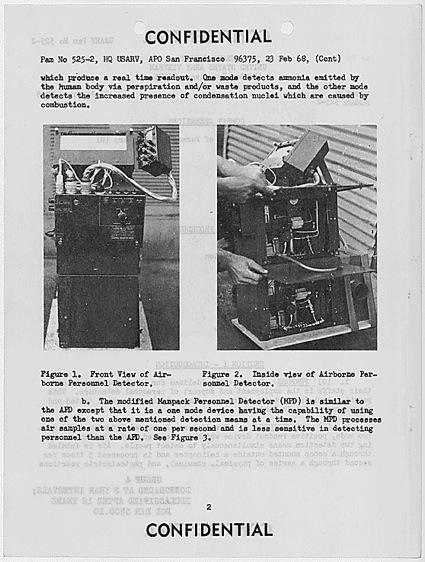

– Young’s account of the tactics deployed by the U.S. army during the Vietnam war was equally fascinating. Some of the technology does indeed foreshadow the use of drones. One was a ‘people sniffer‘, a detector that could ‘smell’ human urine and sweat and thus detect enemy soldiers in hidden positions. This Operation Snoopy (because that was its name) and other tactics are presented in the 1969 video Bugging the Battlefield

Bugging the Battlefield, 1969

Personnel detector pamphlet. Photo: National Archives, via War is Boring

Personnel detector pamphlet. Photo: National Archives, via War is Boring

– another important point Dave Young made is that the military is always trying to remove the agency of the soldier. A soldier can be disobedient, he or she can question an order or strategy.

Don’t miss DNL’s next event: CYBORG: Hacktivists, Freaks and Hybrid Uprisings, it will take place on May 29 and 30 at Kunstquartier Bethanien in Berlin.

Previous posts about the Drones event: Eyes from a distance. Personal encounters with military drones and The Grey Zone. On the (il)legitimacy of targeted killing by drones.