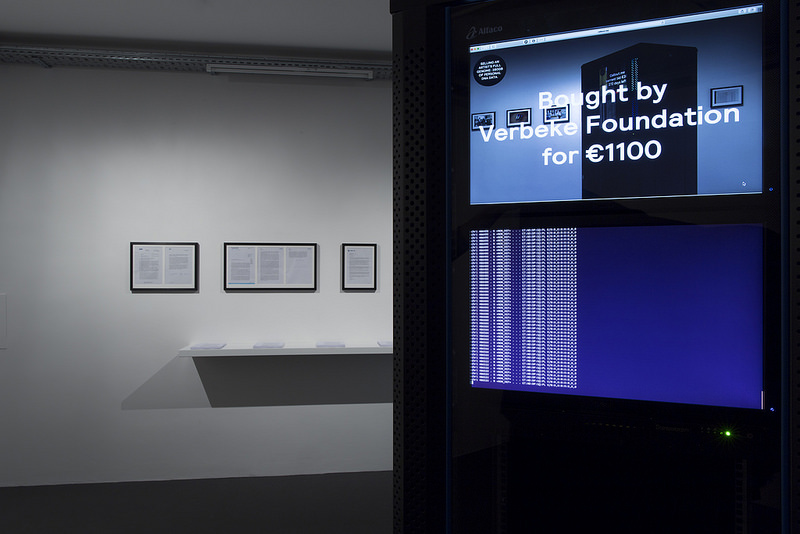

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, exhibition view at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, exhibition view at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

At the end of 2015, artist Jeroen van Loon offered his entire DNA data – 380 GB of personal data – for auction. The starting price was an extravagant 0 euro. Anyone could place a bid through www.cellout.me. A year later, the auction closed and the artist’s full genome sold for 1100 euros to the Verbeke Foundation.

The highest bidder had just acquired an installation composed of the server cabinet where the data are stored, framed pictures documenting the DNA extracting and encoding processes, four letters written by experts as well something more difficult to fully grasp: an individual’s entire DNA self-portrait.

In their letters, experts from very different fields attempt to untangle the meaning and implications of Cellout.me. Auction house Christie’s Amsterdam seeks to estimate the artistic value of the artist’s DNA; specialists at medical center ErasmusMC in Rotterdam looked at the ethical dimension of the artist’s work and what it means to own his genome which they compare to the digital version of an individual. KPMG, a company with expertise “in all things Big Data” investigated the potential fluctuations of value of the artist’s DNA through time. As for cybersecurity company Fox-It, they wrote perhaps the most dramatic note, they underline the fragility of this DNA which needs to be protected from the greed of ‘gold miners’ and other people or companies eager to speculate and profit from this new type of data.

The letters highlight how a project that can be summed up in a couple of words (Artists Sells Own DNA for 1100 Euros!!!) hides various levels of complexity, meanings, ramifications and uncomfortable questions regarding ownership, privacy, the place of DNA in big data and digital culture in general, bioethics, etc.

The selling of human DNA data. Artist talk by Jeroen van Loon at the Aksioma Project Space in Ljubljana on 21 March 2018

What are the consequences of owning someone else’s DNA data? How does this influence the spatial privacy of the biological owner and his family members?

The installation is currently on view at Aksioma Project Space in Ljubljana, Slovenia. I took the exhibition as an excuse to contact Jeroen van Loon and ask him the questions above. And more:

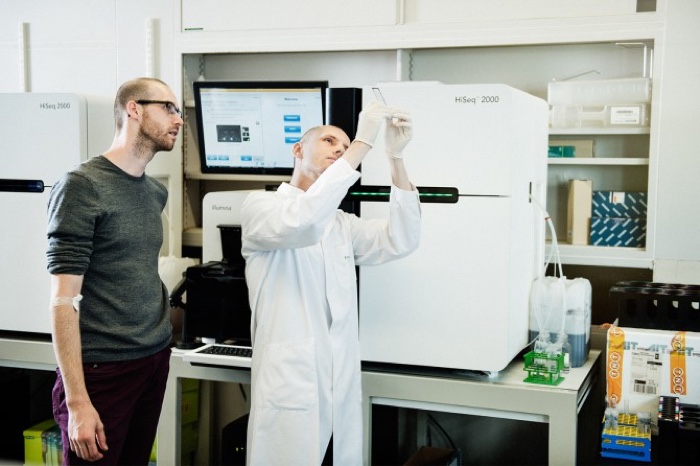

Photo by Erik Borst: In front of the HiSeq DNA sequencer, which takes 2 weeks to sequence a full genome

Hi Jeroen! The idea of selling your full genome might sound a bit abstract and too conceptual to most people. DNA is a very very long sequence of ACTGs (3 billion lines!) Could you briefly tell us about some of the ethical and cultural questions raised by the auction of your DNA data?

The main difference when thinking about selling DNA data (and I mean DNA data, not biological DNA) compared to other types of data – let’s say credit card or social media data – is that DNA data is not constrained to one single person. DNA data is about me, but also about my sister, parents, grandparents and also my son. So when I decide to sell my DNA data, the first question one could ask is if it’s even my data to sell. Who is the owner of my DNA data? Do I have any authorship or copyright concerning my DNA data? Should I inform my family members and ask for consent when doing something with my DNA data? Scientists call this characteristic of DNA data spatial privacy. Further more, if I find your DNA on a soda can and I sequence it, is it then my DNA data?

Apart from the selling questions, one of the main questions revolves around the monetary value of human DNA data. Because, how do you come up with a certain price tag for my DNA data when we discard the production price for the creation of that DNA data? What makes my DNA data any different – and more of less worthy – than yours? To make it more difficult, what we know today about human DNA data isn’t the same as what we might know in let’s say 15 years. The information value of human DNA data changes because of new scientific research. So linking the price tag to the current information level could also be problematic.

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, artist presentation at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, exhibition view at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, exhibition view at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

The most distressing aspect of the work for me is that it projects you into a very uncertain future. Right now it’s probably not very easy, practical nor affordable to faithfully transcribe someone else’s genome and draw profit from it. But one day it might. And since you share the DNA material with your existing and future family, it means that your work might be of concern to them. Did you justify your work to them? How did they react to your project?

Yes, I explained my intentions and what I would do with my DNA data. Everybody found it interesting, some found it a little scary, including myself, and others, like my son, was, and is, too young to think anything about it. I did not ask anybody for consent, either in a formal or informal manner. You could call this egoistic, which it probably is.

The main reason for doing it this way is that you might otherwise not have asked this particular question. The artwork is not a metaphor, narrative or visualisation, it is a documentation of a real life action. And it is this action that creates the questions concerning this future digital culture I wanted to show. If it was not a real life action and thus without consequences, it would not have been able to ask these questions.

This is not to say that this does not scare me sometimes, but right now this discussion is in an ‘ignorance is bliss’ place in my mind.

Photo by Erik Borst: Isolating DNA from blood sample

You asked specialists from various fields to ponder upon the significance of the work. One of them was cybersecurity company Fox-It. In their letter, they insist on the need to protect this type data, because DNA is “the new gold” and “access to the goldmine” should be controlled. Yet, the description of the work states that “The artist decided not to stipulate a contract with the eventual buyer” What motivated this decision? I’m particularly curious about the absence of contract since it is so important to protect your data and encrypt it carefully, especially when the data is so personal.

I came up with the idea to add a contract, which would state what the buyer could and couldn’t do with the DNA data, during the final production stages of the artwork. I think I got cold feet. It was the same reason why I wanted to begin the auction price at the production price of the artwork. Both ideas were abandoned after conversations with fellow artists when I realised they would greatly damage the core idea behind the work. It would create a watered-down version of the artwork.

When content becomes binary code we see the same questions pop up regarding copyright, authorship, piracy, privacy, original/copy, remix and so on. This happened to music, cinema, news, and will happen to our DNA data as well. When DNA sequence technology becomes easier, cheaper and more widely available, more companies/organisations will offer ways of e.g. sequencing, storing, sharing, owning, buying or selling DNA data.

As with all other types of digital content, DNA data will also be (il)legally recorded, shared, hacked, leaked, mixed and so on. My point was to show what kind of new questions could arise when human DNA data was sold, not to find the most secure way of transferring it. The actual selling asks not only these questions but also shows possible implications.

What happened since you sold your DNA data? You just sent the whole installation to the Verbeke Foundation and then it disappeared from your preoccupations?

My focus as an artist is on visualising, documenting and revealing digital culture, not on DNA and its discourse. DNA was only my focus because it became data. So to be very honest; when the work was sold my preoccupation with my DNA data was finished.

I try to keep up a little with news about DNA sequence possibilities. I recently saw a Dutch TV commercial in which they offered to sequence parts of your DNA for your, a sort of 23andMe.com. The fact that this is now on Dutch TV means that we will have to deal more and more with the questions surrounding data and DNA and therefor I feel happy to already have finished the work since I tried to reveal digital culture with this work.

I did write a small text about my final reflections on the selling of my DNA data for Digimag Journal | Issue 75 | Digital Identities, Self Narratives. The interesting part was that a lot of people around me were encouraging me to place fake bids to get higher bids. Even journalists told me they would write about the work if the price would be higher. This really frustrated me, as if a work is only interesting if it’s worth as much as possible. The strange thing was that during the last month of the auction I got the same feeling, ‘the work is useless and failed if it’s being sold for 500 euro…’ Which of course doesn’t matter, it was only my own insecurities. The only thing that matter was that my DNA data was sold. For how much or little didn’t matter, the selling itself was important, not the price. But it did get me thinking about what would change the price. I don’t think there’s any difference in the order in which the 3 billion ACTG’s are positioned, rather I think it could be a difference in context. Who sells it, when, where, how and why, meaning the value of DNA data resides in context rather than in production as perhaps is the case with all art.

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me – selling human DNA data

Have you never been worried by the fact that the work could have been bought by some private company that speculates on data? By Amazon or Google for example?

I did, this was precisely the worry that made me think of the contract and start looking at the production price. The thing that scared me the most was that someone would buy it, analyse the sequenced data so they knew e.g. what my chances are on getting alzheimer’s disease and publishing all this information so my family members could read about their own chances of getting it without having the chance to say ‘no, I do not want to know this right now.’.

During the last 30 minutes of the year-long auction there where four different potential buyers of which one had a relation with the medical industry. What could have happened if Verbeke haden’t bought it, I don’t know, perhaps it wouldn’t be an artwork anymore, it would just be data.

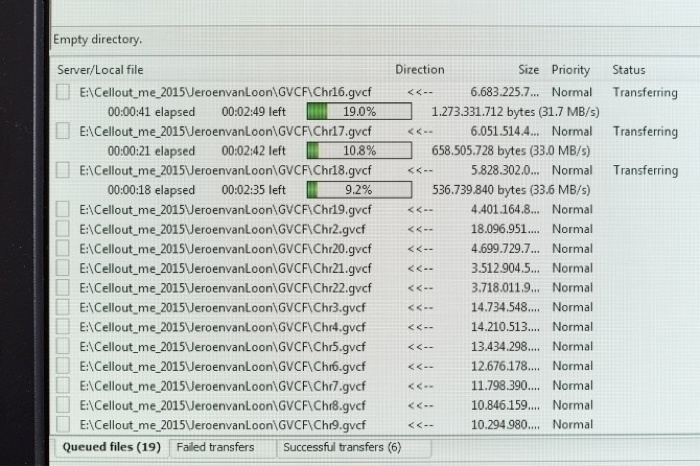

Photo by Erik Borst: In ErasmusMC’s data center: the hardware responsible for storing and analysing DNA

Photo by Erik Borst: Transferring 380gb of DNA data from ErasmusMC’s data center to the artist’s hard drive

Do you think it could turn out that yours was actually a very wise move? That the Verbeke Foundation might do more to protect your DNA data than you (or anyone else) could do? That it now feels some kind of responsibility towards it?

I never thought about it that way. Could be I guess. Since there is no contract they can do whatever they want with the work, sell it, show it, dismantle it, put it in a depot. I don’t have any say in it, so when Aksioma asked me if it would be possible to show cellout.me, I first had to ask if I could loan the artwork. It would be interesting to document the opinion of Geert Verbeke, owner of the Verbeke Foundation, about his responsibility towards the artwork and the data.

Photo by Erik Borst: First step: generating blood samples

Photo by Erik Borst: 3 vials of blood

Was the ‘blood-to-data’ process a long and difficult one? What was it like and who did you work with?

The team of André Uitterlinden (Professor of Complex Genetics at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) helped me with understanding the procedure of sequencing my DNA and the actual sequencing. Through this understanding I could decide how many photos I needed to show the blood-to-data process. All photos were taken by Erik Borst, with which I discussed how the images should look.

After generating a few blood samples the biological DNA was extracted from my blood. The sequencing itself took two full weeks, this was due the fact that my DNA data was sequenced in a 30-fold depth, meaning it was of laboratory quality. When the sequence was finished the data was checked by bioinformaticians, with which I discussed before hand what kind of output I needed for the artwork. The staff was extremely helpful and interested as they saw this work as an opportunity to communicate about their work and DNA in general.

Jeroen van Loon, Cellout.me, exhibition view at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Jure Goršič / Aksioma

I’m also curious about the aesthetics of the piece. The final installation looks like a normal server cabinet, it could host any type of data. What guided your artistic decision to showcase and communicate the process this way? Was it just the most practical option?

One of the most difficult tasks during the production of the work was to think of the medium in which I wanted to show the DNA data. I found it very difficult to create a visual link between the auction and the actual data. In my mind, the medium in which I wanted to show the work didn’t need to be an artistic representation or imagination. The work is not a visualisation, it is a documentation. I struggled with this because I was mainly thinking about how it was going to look inside a gallery. I thought of tripods, pedestals, mounted screens, framed harddisks, printed DNA code and so on, all terrible.

The night before I had to finished my proposal, I got the idea of using a server cabinet (don’t remember how I got the idea), I found it the most honest way of documenting the auction and the data since I could use a screen for each. Showing the actual raw data file on one screen and the realtime auction results through the website www.cellout.me on another, all inside the same object. The tall blackish server cabinet itself is beautiful; it’s nearly the same size as me, the glass door reflects you when your looking at the data, it’s an object that people know, they relate it to data, datacenters, google, facebook and so on. It’s a closed cabinet with the data inside as if it’s an box waiting to be opened. It was the perfect medium to communicate my thoughts, and indeed a very practical one.

What are you showing at Aksioma exactly? The full installation? Other materials?

I’m showing, with the help of the Verbeke Foundation, the full installation.

The presentation consists of the server cabinet, the blood-to-data photo series and the four texts written by Christie’s, ErasmusMC, KPMG and Fox-IT – which have an English translation that the audience can take home.

Thanks Jeroen!

Cellout.me, Jeroen van Loon’s solo show is at Aksioma in Ljubljana from 21 March until 20 April 2018. The opening and artist talk titled “The selling of human DNA data” take place this Wednesday 21 March at 7 pm.

Other works by Jeroen van Loon: An Internet featured in How artists and designers are “materialising the Internet.”