A few months ago, i watched the geopolitical thriller TV series Occupied. The show starts shortly after a hurricane, provoked by effects of climate change, has ravaged Norway. During the following elections, the key promise of the national Green Party is that all fossil fuel production will be cut off. They win the elections and the new Prime Minister initiates the process of replacing oil energy with a thorium-based nuclear one. The EU is desperate to have access to Norwegian oils again and asks Russia to ‘gently’ invade the country. The Russian comply and take the power until oil and gas production is restored. At least that was the plan…

Occupied (trailer)

Well, non-fiction Norway doesn’t seem to have any similar strategy to turn its back on fossil fuel. In fact, the country has recently opened up the Arctic to oil companies so that they can start drilling. All in the name of ’employment, growth and value creation in Norway.’

One of the exhibitions at the intrepid and gripping Bergen Assembly, an art triennial that just opened in the small Norwegian city where rain falls lavishly and tourists embark on fjord cruises, explores how the global decline in oil prices and rising unemployment is hitting the country with the notoriously generous welfare system.

Curated by Mao Mollona, The End of Oil explores possible scenarios associated with the decline of the oil-based economy in Norway. With the prosperity of the oil-boom years likely coming to come an end and society finding itself on the brink of an infrastructural change, these scenarios relate to questions about our relationship with nature in a wider sense.

The End of Oil comprises two artists’ films. The first one is a short animation video by Phil Collins. It’s called Delete Beach and stars a schoolgirl who joins an anti-capitalist resistance group that gets high on fossil fuel energy. It’s as brilliant as you can expect but the second film is the one i found most moving….

Massimiliano Mollona and Anne Marthe Dyvi, Oilers, Still from the video

Oilers, directed by artist Anne Marthe Dyvi together with anthropologist and curator Mao Mollona, is a short documentary that follows the construction of a Norwegian off-shore oil platform over the course of the year 2015.

What i found extraordinary about the video was that it charts the construction of the super large oil platform from the workers’ point of view. Which certainly contrasts with the kind of images you usually see of the construction of offshore oil platforms:

The production platform for the Edvard Grieg field

I don’t know how i was imagining the construction of an oil rig but i was certainly surprised to read that huge bits and pieces of offshore platforms are built across the world and then pulled out in the ocean to be assembled together.

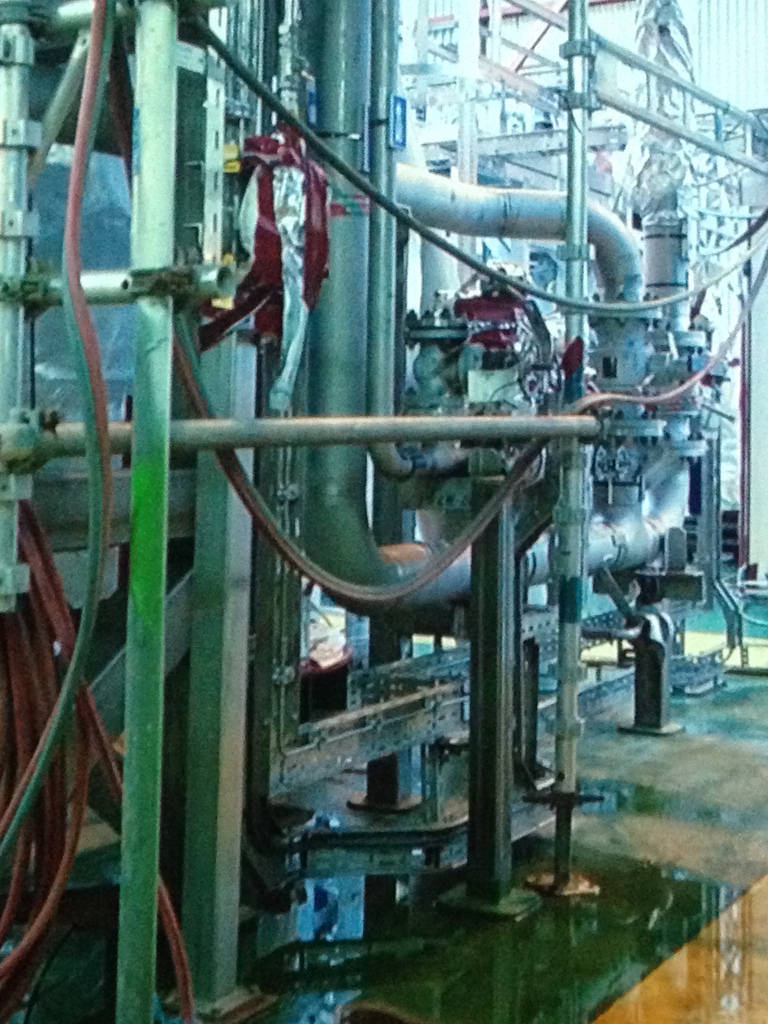

But back to the Oilers video. The images show life in the Norwegian offshore yard of Kvaerner Stord. There’s the side you expect to see: the beige rooms where the workers relax and meet, the canteen where they eat, the security measure they need to follow, the huge scale they work on, etc. The images are splendid, the tools and tech are impressive and waltz in front of your eyes in silence. But the film also gives the workers a voice. Unedited images show workers protesting against the prospect of losing their job, labour unions leaders swearing to dubitative workers that ‘there is not sunset in oil’ and negotiating the cuts to make in order to win the next building contract, bands singing at hot dog parties that celebrate the completion of the finished platform, etc.

Oilers (a bad photo i took during the screening)

Oilers (a bad photo i took during the screening)

The backdrop of Oilers is a dramatic one:

The price of oil has dropped to around $30 a barrel last winter and at roughly $44 today, it is still far off from the $115 paid in June 2014. The plunge in the price of the barrel reveals the full extent of the Norwegian economy’s unhealthy dependency on oil and gas. According to newspapers, the energy industry accounts for 15% of Norway’s economy, more than half of its exports and 80% of the state’s income.

To make up for the oil crash, companies strive to reduce cost and increase productivity (at the expenses of the workers’ wages and living standards obviously.) Unemployment is rising. In 2015 about 30.000 jobs in the oil industry disappeared in Norway.

End of Oil. Installation View, Bergen Assembly 2016. Hagerupsgården, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

End of Oil. Installation View, Bergen Assembly 2016. Hagerupsgården, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

The snippets of discussions and dissent overheard in the film tell the story of a country that had it too good for too long and that is forced to ‘envision a future without the certainties of the past.’ The situation in Norway is certainly striking but it find echoes pretty much everywhere else in Europe where social democracy is at bay.

The project The End of Oil wants to create a conceptual bridge between the visible infrastructures of oil and the invisible and sensuous structures of feeling, including fears and hopes for the future and memories of how Norway was in the 1970s before the oil arrived.

Oilers is a splendid short documentary that shows the human side of the oil crisis. You root for the workers and hope they’ll get a job building another platform (they won’t, their employers didn’t get the contract in the end) but you know it would be wrong. This industry needs to disappear and this is going to hurt.

End of Oil. Installation View, Bergen Assembly 2016. Hagerupsgården, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

End of Oil. Installation View, Bergen Assembly 2016. Hagerupsgården, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

Bergen Assembly 2016. Bergen Gamle Hovedbrannstasjon (entrance of the ex fire station where you can see the film), Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

The Bergen Assembly takes place in various venues around Bergen, Norway until 9 December, 2016.