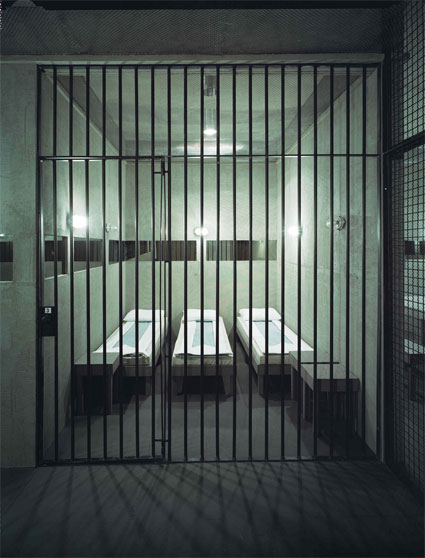

Death-Row Outdoor Recreational Facility, “The Cage”, Mansfield, Ohio. Photo by Taryn Simon (via el pais)

Death-Row Outdoor Recreational Facility, “The Cage”, Mansfield, Ohio. Photo by Taryn Simon (via el pais)

The Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin is dedicating an exhibition on prison architecture. I happened to be in town the day of the opening. Arriving very early that evening meant that i could not only skip the donne ingioiellate and the rest of the usual aperitivo art crowd but i could also listen to a panel in which the architects invited to contribute to the exhibition shared their view on prison architecture. I don’t think i would have enjoyed the exhibition that much had i not attended those talks.

11 international architectural studios were challenged by curator Francesco Bonami to leave aside the world of lavish towers, swanky condos or spectacular bridges for a moment and turn their attention to the far less glamorous correctional facility. They had to design a life-size cell equipped with all the essential features the inmates require and from then on engage in a reflection about the prison system and its corollaries: the restriction of freedom, human rights, instruments of surveillance and control, etc. Unsurprisingly most architects started their statement by saying that the invitation from Bonami posed an ethical dilemma for them.

The architects were very tempted to say ‘no’ to the invitation. The challenge they had to face was formidable as the organization of space in prison often embodies the legal and political principle of punishment for a crime.

Some of the participants dutifully designed the three by four metre space required by the curator. Others worked a way around their artistic homework.

DW5 Bernard Khoury (Beirut, Lebanon) POW 08 CONOPS

DW5 Bernard Khoury (Beirut, Lebanon) POW 08 CONOPS

Bernard Khoury, who was the only one in the panel who had actually set foot in a prison in the past (due to some misunderstanding), didn’t hide the fact that the request from Bonami seemed to come out of the blue. His Beirut-based studio is usually dealing with the realization of shopping malls, nightclubs, restaurants, hotels, villas for the rich, etc.

Khoury’s schizophrenic design envisions a kind of portable self-propelled apparatus worn by a prisoner of war returning to his or her homeland. He would be harnessed inside the device and use his arms to slowly, very slowly crawl his way across the enemy lines and back to his own camp while the technology inside the device would send back some useful data to the enemy. The prisoner becomes unwillingly a traitor, a sort of drone that informs the opponents. What could be more humiliating?

Prison? We Thought You Said Prism

Prison? We Thought You Said Prism

Jeff Inaba and SLAB Architecture‘s project started as a question. Not the one that the curator had asked ‘what can architecture do for prisons?’ but instead, they wondered ‘what can prisons do for architecture?’ Their installation explores how color is used to judge and organize prisoners, and draws correlations to forms of judgment that are made in the field of architecture.

Image via On Deadline

Image via On Deadline

In the U.S. colour is used to separate, divide and to create misunderstandings. In some prisons, inmates with black skin are separated from those with a white skin (the practice is justified as a mean to avoid gang violence). If a prisoner is under medication or if he or she is violent, they have to wear a uniform of a particular colour. Colour in prison predetermines and defines what prisoners are. And of course, there’s pink. Pink underwear is worn by prisoners in some prisons in Arizona and other States as a form of humiliation.

Does the Punishment Fit the Crime?

Does the Punishment Fit the Crime?

Diller Scofidio + Renfro embraced the exercise as an ethical challenge, because, in their view, designing a prison cell would mean, in a sense, endorsing the system. They referred particularly to the carceral system in the U.S. where the concept of rehabilitation has been almost abandoned. Today the focus is on protecting society from prisoners and there’s very little attempt to bring back an inmate into society. The architects studio designed Does the punishment fit the crime?, an interactive interface that you can swing around an empty cell to determine what its spatial configurations will be, depending on the degree of security required and type of crime the detainee has committed.

project_ (Anna Miljacki and Lee Moreau) used the cell space to set up a small exhibition space that gathers on the floor facts and figures about the relationship between U.S. prisons and the economic and industrial system, commenting on its controversial and profit-making essence.

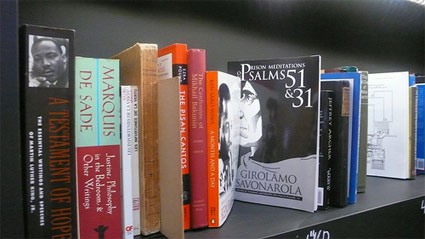

Ines & Eyal Weizman chose to envision the prison cell as a space of intellectual production. They collected books and artworks produced inside a carceral environment to investigate whether there is a relationship between cells and the kind of writing emerging from there. The result was an impressive library of books ordered according to the time the author has spent in prison. It was extremely thought-provoking and surprising to see the letters of Saint Paul in the same library as the novels of the Marquis de Sade, the works of Jean Genet, Marthin Luther King, Girolamo Savonarola and the writings of political dissidents like Gandhi and Antonio Gramsci. The collection of “prison literature” will be donated to a correctional facility after the exhibition.

Marco Navarra’s NOWA was the only architecture studio which ventured outside of its ivory tower and actually engaged with people living inside prisons (inmates, guardians and medical staff). They collaborated with two prisons, one at Caltagirone, in Sicily, and the Casa Circondariale di Torino (Turin Correctional Facility), asking the inmates to draw a cell, real or imagined. The hundreds of designs were then turned into small-scale models and displayed inside a cell covered with Guantanamo’s style prisoners overalls. The final result was very disappointing but some of the issues he raised during his presentation were worth some further investigation. For example Navarra underlined the fact that our society keeps on replicating the same model that saw the light in the early 19th Century, while the whole world around them is changing at an increasingly fast pace.

I’m really looking forward to get my hands on the catalog of the exhibition (is it finally out?) and i’ll certainly bike back to the Fondazione to see YOUprison more quietly as soon as i’m back in town. Apart from the architecture projects, the show also includes a series of works by artists. The ones that i need to go back to are the videos of Ashley Hunt. More soon ladies & gentlemen….

Artur Zmijewski, Repetition, 2005. Videostill

Artur Zmijewski, Repetition, 2005. Videostill

My flickr photo set. Image on the homepage: Ashley Hunt, I Won’t Drown on that Levee and You Ain’t Gonna’ Break my Back, 2006. Courtesy Ashley Hunt.

The exhibition runs at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, until 12 October 2008.