Please meet Boutique Vizique! Boutique Vizique is Hendrik Leper and Stijn Schiffeleers, plus a bunch of other artists or experts they invite to collaborate with them once in a while.

Stijn and Hendrik come from Ghent. If you’re into new media art, creativity and design you might have heard of that small-ish Belgian city. They trained as photographer, started working mostly with video, collaborated with sound artists and are now developing interactive installations. The kind we like: playful, witty and beautifully executed.

Portrait of Boutique Vizique by Koen Broos.

You both studied photography at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium. How did you end up working on interaction design, reactive installations, performances using real time live generated images and sounds?

Boutique Vizique was originally intended to be a short-term venture. A few years after we had left the Academy, we decided to collaborate on a small video project which was supposed to last for two weeks. But two weeks became three, and this summer we are celebrating our seventh year as a collective. It has been a gradual growth and looking back reveals an organic development of our practice. Originally doing mainly video work for musicians, DJ’s, opera singers, actors and dancers, we slowly made the transition to a more three-dimensional approach. We both look back at those early experiments with a blush on our face, but nevertheless we were able to let things sprout out of these early, naive try-outs.

A Dustbunny

A Dustbunny

So from the beginning, it has been like hopping from one stone to another, leaving a zigzag trail of encounters, realizations and reactions. One project lead into another and we tried to remain open to all of it. Boutique Vizique is rooted in curiosity and its exploring nature also reflects our previous wanderings. It is clear that we both like to wander and, as a result, quite often find ourselves “off-track”. Last October at Matchmaking, an annual festival for electronic arts and new technology in Trondheim, we structured our lecture around the thought of ‘being lost’. Supported by a quote from Rebecca Solnit’s essay ‘A Field Guide to Getting Lost‘ we discussed the role of the unknown and open doors in the line of our work. We like to believe that, as artists and human beings, every time we feel lost, it gives us an opportunity to stumble upon something new. Slowly, step by step, we have mastered different tools which are not necessarily related, but always find an integration under the Boutique Vizique umbrella.

You often develop your piece with the collaboration of other people. How does the creation start? You get an idea and look for someone who has the skills that you need? Or you meet someone you’d like to work with and decide on a project together?

Throughout the years we have collaborated in various ways on a wide range of distinct projects. Some of these collaborations were pure technical and some emerged because other artists shared similar interests. Boutique Vizique germinated from a project with two DJ’s and this collaborative aspect became a natural ingredient in our practice in those first years. A handful of music bands with complete different styles asked us to provide video projections for their concerts and we also worked closely with AIM Records, a small Ghent based independent label that gave us a lot of freedom in our creations.

Os Gauchos do pelatao

Os Gauchos do pelatao

To a certain level we were fine with just delivering a visually interesting backdrop, but simultaneously felt the urge to look for a more direct cross-pollination. ‘Super Setup’, ‘Starbot Ensemble’, ‘Early Electronics’ and ‘Os Gauchos do pelatão’ are four projects that grew out of the desire to come to a true collaboration where sound and video got completely interwoven. Around that time we also started working closely with other forms of performing arts and theater. We had to learn about the dynamic relation between story, performer and video; and various new ways of interaction were applied to finally come to a complete integration of all components.

A turnaround occurred at the moment we took time to convey our personal ideas independently and looked for a format that would fit our personal needs. After 3 years working in collaboration with performers we began to develop interactive installations autonomously, without any specific assignment and far away from any stage or other limitations. Following collaborations mainly arose mostly out of technical needs or the lack of certain skills. We involved other artists and engineers to create specific sections like a sound file, a printed circuit board or a piece of code.

Since then, people have been coming and going and it makes sense we will continue to work this way in the near future. After seven years we often run on autopilot mode when dealing with each other during certain stages of the development process. Having completed so many projects we understand, through a minimum of communication, where the other one wants to go and it all feels very natural that way.

You worked several times on installations for kids. What are the challenges and advantages of developing projects that are aimed to be enjoyed by children?

Babble

Babble

Our older video and performance oriented work had been embedded with a decent amount of playfulness long before we made our first reactive sculpture. It seems that having this playful facet deeply rooted in our work made it almost inevitable not to develop projects specifically for children at some point. We never had an outspoken intention to do so, but also did not doubt a second at the moment we were asked to make a real time video choir for a children’s music festival. Later on, we evaluated the pros and contras and from a brief look at the body of work following Babble, you can tell we enjoyed it. Seeing all those young faces light up every time we present our work is highly rewarding and it is this kind of appreciation that keeps us going I guess.

Challenges related to child and adult specific projects are often very similar. In fact we consciously endeavor to create installations that are intended to be enjoyed by both young and old. It is obvious that part of our plan is to awake the child in each one of us. And since play, poetry and simplicity are a constant in our work those challenges seem to overlap quite often. Any major difference probably revolves around the threshold of your interfaces. With children as a target group you cannot afford to make extreme subtle changes in your output. Everything needs to be more straightforward and responses from sensors must immediately cause an impact on the environment. Simultaneously the interface needs to induce an intuitive interaction and encourage participation without any instructions. Kids luckily do not need much of an explanation and often copy others to come to an understanding of what is going on.

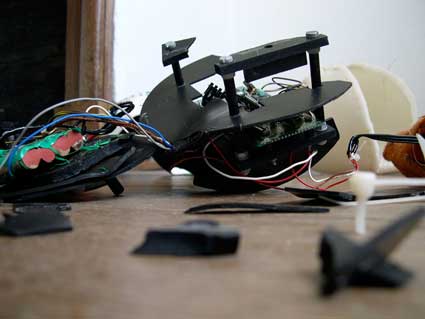

When working with children, you also might consider building everything a little stronger. The first version of our Dustbunnies, for example, got smashed under the weight of some kid, exactly two days after the opening. Five months of work only needed a 10 year old foot to flatten and short circuit every component inside of it. Funny thing is that Dustbunnies was never intended for a young audience, because otherwise we would not have created a shape that does resemble a soccer ball to such extend. We learned a lot from that experience and it is actually wonderful to have these limitations push your creativity to another level. How do you make a large swinging object that won’t chop off some kids head? Try it, it’s a great exercise!

Dustbunny “fried”

Dustbunny “fried”

Finding a satisfying balance between the experience for the child and our personal creative impulses is probably the most intriguing challenge every time we come up with a new installation. How do you create a situation that expresses your vision and simultaneously intrigues the children? You can hang big spheres in a space and project warped faces around them, but what reference does a child have to the elements you use? In order to keep the experience for everyone as open as possible, we intentionally never create a narrative. The circumstances we set up always require a certain level of communication, verbally or not, and multiple senses get stimulated at once. Every installation needs to be explored creatively and can be approached both as an individual or within a group. By steering these conditions we aspire to find a right balance for every child or at least something enjoyable for each one to be found.

The main advantage of developing installations for children is that in general they have less social boundaries. They are allowed to play and seem to connect easier with someone they don’t know. It is also beautiful to see them sink into in the environment we set up and make them forget about the world around them. The greatest advantage of course is that we ourselves are still allowed to be kids. We can play as much as we want this way!

‘Kontakt’ and ‘Stopkontakt’ invite the audience to use their body as a conductor between electrical circuits. How did you get the idea to work on that piece? How did the public react to it? Did you observe any unexpected behavior?

Image by Lies Declerck

Image by Lies Declerck

Kontakt was conceived during workshop, called Media Knitting, at DEAF 2003, the Dutch Electronic Art Festival in Rotterdam. This is where we met Karmen Franinovic, who at that point was getting her Master’s degree at the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea in Italy. The workshop was set up so people with different tool sets could possibly connect and collaborate. Karmen was working on a custom-made pressure sensor using conductive foam and we had just received our first Teleo module. We combined both components and a bit later we were all holding hands to test how conductive our bodies actually were. Kontakt was born and we constructed a prototype version in the stairwell within the three-story building of V2. Bright orange metal plates, with hands painted on them, encouraged visitors to use their bodies and form a human chain between them. Several of these active touch points where spread throughout the space and connecting caused a set of sound and video sequences to be played. The interface required people to collectively explore the space, as it was impossible for a single visitor to make connection between the various points. Holding hands, kissing and using differently conductive objects to modulate the output all became part of the interaction. The human skin and body, mobile and unpredictable, became the sensor and the actuator of this active space.

A few months later we were commissioned to create an installation for the Happy New Ears Festival in Kortrijk, Belgium. The location was a formerly blocked off part of the directors house in an old textile factory. The space was submerged in a gloomy atmosphere as it had been collecting dust for more then a decade. The setting itself was too impressive to ignore and we had the Kontakt concept ready to unfold. Inspired by the space, we developed Stopkontakt, meaning wall outlet in Dutch, in a very site specific format.

Four rooms and the grand central stairway got wired up, filled with touch points, speaker and data cable. As an output we picked various analogue objects, like a kitschy pendulum clock, some plastic bird flutes, a water dripping valve, an old record player and more junk.

Although the system is very simple, it remains surprising to most visitors that you can start a coffee grinder with a handshake. Questions from parents about possibly getting shocked or failing pacemakers pop up regularly. While the grown-ups look and try to figure out how it all work, the kids do not seem to bother and just go wild holding hands, feet and knees with friends, family and complete strangers.

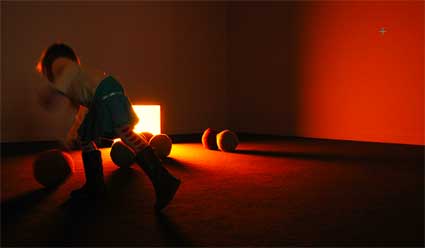

What are you trying to achieve with Tortuga? Do you plan to develop the project further?

Tortuga is another good example of how Boutique Vizique functions as a learning place. The technical part of it originates from a class on PCB design and microchip programming I took last year. Its circuit board is drafted to contain an ultrasonic transceiver and a Zigbee module in order to measure the distance between two objects without any other external hardware involved. From this pure technical starting point it has grown out to a personal research project and Tortuga is actually an extended prototype for a larger installation that has been put on hold for various reasons. Its concept is formed around creating several large mobile structures and the ability to move these objects throughout a space, dependent on their acceleration and their physical location. It is one of those projects that could have stayed half finished in a closet for the rest of our life, but when curator Virgil Pollit asked us to be part of a group show called ‘Fertile Grounds’, we decided to continue and build some iceberg structures around the already functioning mechanical basis.

When I fantasize about the full-scale version I see some undefined objects being moved around by a group of people in a free-flowing way. The motion is smooth and will only be interrupted if a sudden push occurs or in case the objects come within a minimal distance to each other or a wall. All visitors have to collaborate to generate a fluent movement and I am into the idea of using a loud sound or earplugs to prevent the audience from communicating verbally. I guess with Tortuga I am looking for new forms of interaction and ways to provoke pleasures similar to the one I get from moving rocks in a river. The ‘useless’ act of relocating random objects within a limited space, knowing they will move again once you have left, fascinates me. Still, while moving river rocks might result in a sculpture or a structure, Tortuga consciously tries to avoid any logic result or outcome. Although never choreographed, it will probably end up looking more like a dance than a sculpture at certain moments. The installation becomes an engine for a performance.

When I fantasize about the full-scale version I see some undefined objects being moved around by a group of people in a free-flowing way. The motion is smooth and will only be interrupted if a sudden push occurs or in case the objects come within a minimal distance to each other or a wall. All visitors have to collaborate to generate a fluent movement and I am into the idea of using a loud sound or earplugs to prevent the audience from communicating verbally. I guess with Tortuga I am looking for new forms of interaction and ways to provoke pleasures similar to the one I get from moving rocks in a river. The ‘useless’ act of relocating random objects within a limited space, knowing they will move again once you have left, fascinates me. Still, while moving river rocks might result in a sculpture or a structure, Tortuga consciously tries to avoid any logic result or outcome. Although never choreographed, it will probably end up looking more like a dance than a sculpture at certain moments. The installation becomes an engine for a performance.

Showing the first version of Tortuga in a gallery environment has taught me a few lessons. Although the exhibition resulted in some fruitful conversations and animated interactions, it certainly was too early to present this work to a larger audience. As an artist you can not expect visitors to jump right into your fantasy world. They need a grip, something that guides them through your brain. Leaving them clueless just resulted in an uncomfortable situation and my hopes for now, Tortuga is buried in our closet again. Maybe its dream will be picked up again some day.

Can you explain us what Beat Blocks is about? And what makes it particularly exciting for you?

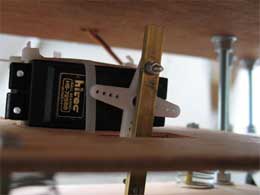

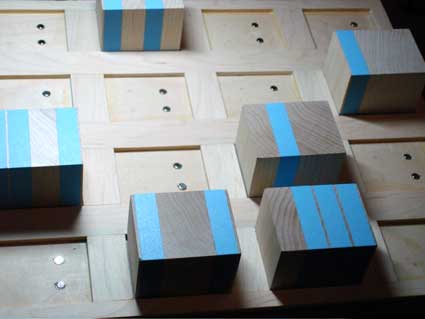

Beat Blocks is the result of a series of encounters with Jeff Hoefs. After I moved to San Francisco, Jeff became one of the new people in my life with whom I like to share my thoughts and dreams about physical computing. One day we decided to challenge ourselves with the design of a tangible interface that could function as a sequencer and would cost less than 300 dollars. After some initial tinkering the idea of using wooden blocks on a grid popped up and the next meeting we spend brainstorming about all possible ways to read out the different values using a relatively cheap technology. Our thoughts grew out to a project and at this point we have a functioning prototype and are in the midst of developing a second and extended version. So the way this project originated, without any request or budget from the outside world, is already pretty exciting to me.

Beat Blocks is the result of a series of encounters with Jeff Hoefs. After I moved to San Francisco, Jeff became one of the new people in my life with whom I like to share my thoughts and dreams about physical computing. One day we decided to challenge ourselves with the design of a tangible interface that could function as a sequencer and would cost less than 300 dollars. After some initial tinkering the idea of using wooden blocks on a grid popped up and the next meeting we spend brainstorming about all possible ways to read out the different values using a relatively cheap technology. Our thoughts grew out to a project and at this point we have a functioning prototype and are in the midst of developing a second and extended version. So the way this project originated, without any request or budget from the outside world, is already pretty exciting to me.

Most fascinating about the interface is its simplicity. A wooden grid and a series of blocks form an uncomplicated interface that is completely self-explanatory. As a user you can create and manipulate a small sound loop by physically re-arranging the wooden blocks within the grid. Doing so will turn the matrix into a rhythm sequencer that operates at a 1/16 note resolution. Each block has a pattern of colored stripes representing 1/4 measures, directly indicating what kind of sequence the underlying system will play. The sequence runs in a continuous loop and a LED indicates the speed of the loop that can be changed by means of a simple slider. The direct relation between these minimal visual aspects and the instantaneously generated sound makes ‘Beat Blocks’ very accessible to anyone, even with little or no musical background. Since the whole system generates a MIDI output, it can be hooked up to a lot of other hardware devices.

Another exciting feature is that its unsophisticated first design can be further developed in numerous directions. The layout of the PCB allows us to connect multiple grids simultaneously and the magnetic connectors could be build into any other shape. Its flexibility enables Beat Blocks to be used for very different purposes and various situations. It could be part of an interactive museum display and so far we have plans for constructing ‘Beat Blocks’ both as a performance tool and as an installation. The possibilities that our basic structure offers have also seem to inspire other people. A while ago, for example, we read on a blog a comment by a visually impaired person who was wondering if the striped pattern actually could be perceived by touch. A wonderful thought and the question actually motivated us to include this facet in our next version. It also got us both excited about creating a ‘Beat Blocks’ blog to share our ideas and be open to suggestions for potential variations.

You are both from Belgium right? How does the country or your region support your work? Do some of your pieces get financed? Do you receive many opportunities to teach and show your work?

Continue reading the interview with Boutique Vizique.