Designer Tuur Van Balen is currently working on a very intriguing project called Pigeon d’Or (“golden pigeon”). From the information i found online, i understood that Pigeon d’Or involves manipulating the metabolism of pigeons and turning them from urban nuisance to winged dispensers of a soap-like substance that would contribute to making cities spic-and-span. If you’re in Brussels you can check out the work in progress at Feel Home, an exhibition at CC Strombeek that builds a bridge between design and contemporary art. Tuur’s work is in good company there (Rem Koolhaas, Gordon Matta-Clark, Mario Merz, Jacques Charlier, Donald Judd, Liam Gillick, Luc Deleu, etc.) and I hope to report from the show if our friend Eyjafjallajökull allows me to fly there.

Just before the opening of Feel Home, Tuur Van Balen was showing another of his most recent projects, Synthetic Immune System, at the Impact! exhibition at the Royal College of Art in London. The project harnesses Synthetic Biology’s potential to turn us into our own doctors and pharmacists. Our immune system would be externalized, metabolic processes would be outsourced to external micro-organisms, such as yeasts, that would sense and diagnose anomalies in our body to produce and deliver chemicals accordingly.

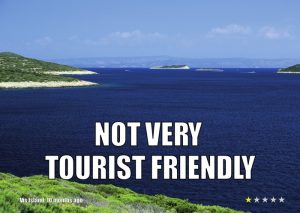

View of Pigeon d’Or at the Feel Home exhibition

View of Pigeon d’Or at the Feel Home exhibition

That gave me a double opportunity to catch up with Tuur:

First, the cleaning pigeons! Can you tell us what your new project, Pigeon d’Or, is about?

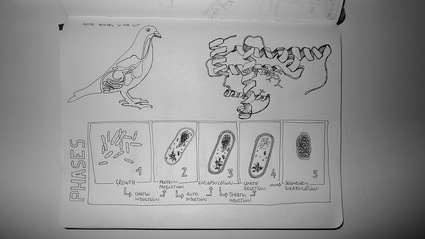

‘Pigeon d’Or – Urban Metabolisms part 2’ is a project I’m currently working on. I’m exploring how pigeons can serve as a (open source) platform and interface for synthetic biology in an urban environment. By modifying the metabolism of pigeons, and specifically the bacteria that live in their gut, synthetic biology might allow us to add new functionality to what is by many seen as flying rats. This would happen through feeding the pigeons special bacteria and would be as harmless to them as eating yoghurt is to us.

In the ‘Feel Home’ exhibition in Brussels, I’m showing work-in-progress of this project. I’ve designed a contraption that would allow these pigeons to become part of your house, part of the architecture. This pigeon house is attached to your windowsill and allows you to feed the pigeons, separate and select them and direct them through different exits.

Further on in the project, I will continue to explore pigeon-metabolisms and attempting to create bacteria that would allow a pigeon to defecate biological soap.

I’m working with pigeon fanciers (the English word for people who breed and keep pigeons for racing or other competitions), both in Belgium and in London. I’m also being advised by scientists from the Centre for Synthetic Biology at Imperial College London, with whom I’ve been working on various projects over the past couple of years. It’s interesting to see the overlaps between two fields that might at first sight not seem to have much in common.

Mr Stratton in London

Mr Stratton in London

Mr Laermans in Lubbeek

Mr Laermans in Lubbeek

The project came out of earlier explorations of the idea of urban metabolisms: a brewery that catches wild yeasts in the middle of Brussels, and my earlier project My City = My Body. I like to think of a city as this vast and incredibly complex metabolism of which the human species is the tiniest of fractions: tiny yet intensely linked into an intricate organic embroidery beyond our understanding. It is in this hugely complex fabric that (future) biotechnologies will end up.

Experiment with pigeon metabolism using food colouring

Experiment with pigeon metabolism using food colouring

The idea of this project partly originated when working with Imperial College’s iGEM team (International Genetically Engineered Machine competition), which I’ve been doing for the past two summers. The team of undergraduate students came up with an method of delivering medicines to the human gut (getting it past the acidity of the stomach) using bacteria for protein production and delivery. When refined, this technology might have incredible advantages over today’s medication. However, I was interested in exploring the potential implications of modifying such metabolisms on a larger scale.

Why pigeons, you might wonder?

To me feral pigeons present themselves as the ideal platform and interface for open-source biotechnology. While seen by many as venom, one could argue they’re actually a product of biotechnology as their ancestors were designed to deliver post, spy during the war, race, tumble of just look pretty. He might not have phrased it that way, but that is one of the reasons Charles Darwin became a pigeon fancier. (And so is the Queen of England, in fact, the British Royal Family first became involved with pigeon racing when being given pigeons by King Leopold II of Belgium, in another trans-channel pigeon project). Mostly though, it is the rich culture around pigeon racing that was so inspiring for this project: from the refined pigeon-psychology to the social and economical practices.

Now let’s get to Synthetic Immune System. The text of the project says “Synthetic Biology’s potential to make healthcare more personal and participatory might turn us into our own doctors and pharmacists”. Do you think it is likely that more power will be into our own hands? i have the feeling that the trend might be to give us less control in almost all aspects of our life.

Now let’s get to Synthetic Immune System. The text of the project says “Synthetic Biology’s potential to make healthcare more personal and participatory might turn us into our own doctors and pharmacists”. Do you think it is likely that more power will be into our own hands? i have the feeling that the trend might be to give us less control in almost all aspects of our life.

You might be right, perhaps it is more likely that people will be given less control in many aspects of life, including interactions with their own body. But I’m not really interested in what is likely. I think the interesting questions come from what is possible. And it is very possible that synthetic biology might empower people to practice healthcare in entirely different ways. Cheaper sequencing could allow medicine to become more personal, tailored to one’s genetic predisposition. Homemade biosensors might give more people the ability to detect infections or certain diseases. And bio-synthesis of drugs might make medicines more specific and their production cheaper and on a smaller (even domestic) scale, not just done by big pharmaceutical companies. However likely that is, it is possible and therefore relevant to think whether we like it or not.

The synthetic immune system need feeding every evening to produce for the person’s needs overnight. i didn’t understand where the different remedies would come from.

The synthetic immune system need feeding every evening to produce for the person’s needs overnight. i didn’t understand where the different remedies would come from.

The different remedies are being produced by a variety of tailored yeasts. Yeasts are one of the chassis used in synthetic biology, together with various bacteria. The yeasts in the synthetic immune system would be specifically designed for that person, to monitor for anomalies according to his or her genetic predisposition and lifestyle: e.g. if you’re vegetarian, one of your yeasts can monitor for vitamin B12 deficiency and when it detects you don’t have enough, the yeast produces the vitamins for you. Because yeast is alive, it needs to be fed with water and sugar.

I choose yeast because people have a long history of interacting with yeast in the making bread or beer. When researching for this project, I visited the Cantillon Brewery in Brussels, where they still make Lambic and Geuze beers exactly as they did over 100 years ago, using wild yeast. (photos.) Part of the brewing process is exposing the boiled wort to the air of Brussels for one night, to catch the wild yeasts. As I was standing there, seeing the beer being pumped into the giant copper cooling tun in a draughty attic, I couldn’t help but wondering if my breath and sweat were influencing the beer?

The device looks pretty scary. Was it a design choice or necessity?

The device looks pretty scary. Was it a design choice or necessity?

You think? I’m sure the world of medicine has produced scarier devices. No seriously, I’m hoping it looks intriguing enough to take you into the story and make you imagine what it would be like to interact with your body in such a way. My intention is not to sell synthetic biology, neither to paint a dystopian scenario; maybe that explains the ambiguous aftertaste?

Thanks Tuur!

All images courtesy Tuur Van Balen.

You have until May 10 to visit the Feel Home exhibition at CultuurCentrum Strombeek, in Brussels. Mon-Sun 9am-10pm. Free entrance.

Previous works by Tuur Van Balen: Goodnight/Good-bye, London Biotopes: Exploring potential City – Body ecologies and My City = My Body – Biological Interactions with and in the City.