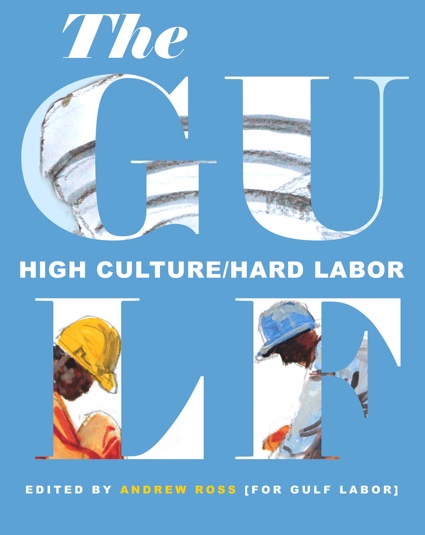

The Gulf. High Culture/Hard Labor, edited by Andrew Ross for Gulf Labor. With a foreword by Sarah Leah Whitson from Human Rights Watch.

Publisher OR Books writes: On Saadiyat Island, just off the coast of Abu Dhabi, branches of iconic cultural institutions, including the Louvre, the Guggenheim, the British Museum and New York University, are taking shape to the designs of starchitects such as Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid, and Norman Foster. In this way, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) seeks to burnish its reputation as a sophisticated destination for wealthy visitors and residents.

Beneath the glossy veneer of the Saadiyat real estate plan, however, lies a tawdry reality. Those laboring on the construction sites are migrant workers who arrive from poor countries heavily indebted as a result of recruitment and transit fees. Once in the UAE the sponsoring employer takes their passports, houses them in sub-standard labor camps, pays much less than they were promised, and enforces a punishing work regimen. If they protest publicly, they risk arrest, beatings, and deportation.

For five years, the Gulf Labor Coalition, a cosmopolitan group of artists and writers, has been pressuring Saadiyat’s Western cultural brands to ensure worker protections. Gulf Labor has coordinated a boycott of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and pioneered innovative direct action that has involved several spectacular museum occupations. As part of a year-long initiative, an array of artists, writers, and activists submitted a work, a text, or an action.

Workers at an NYU Abu Dhabi construction site. Sergey Ponomarev / New York Times. Via Jacobin mag

Workers at an NYU Abu Dhabi construction site. Sergey Ponomarev / New York Times. Via Jacobin mag

Hans Haacke, Saadiyat Island, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, 2011. More images from the series on Ibraaz

Hans Haacke, Saadiyat Island, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, 2011. More images from the series on Ibraaz

Photo: Mussafah camp, home to New York University Abu Dhabi workers, courtesy Gulf Labor. Via art info

Photo: Mussafah camp, home to New York University Abu Dhabi workers, courtesy Gulf Labor. Via art info

Some 15 million migrant workers, mostly from South Asia, form the vast majority of the labor force in most Gulf states. In the UAE and Qatar, 90 percent of the work force and the population are migrant workers (both white collar and blue collar.) No matter how many years they have lived and worked there, or even if they were born there, these people have no voting, representation, or association rights. Thousands of them are currently working on construction sites to create Saadiyat Island (“Island of Happiness”), a £17bn cultural hub in Abu Dhabi that will soon host the new premises of international cultural institutions such as New York University, the Louvre and the Guggenheim.

Gregory Sholette, Saadiyat Island

Gregory Sholette, Saadiyat Island

Hans Haacke, Saadiyat Island, Museum Construction Site, 2011. More images from the series on Ibraaz

Hans Haacke, Saadiyat Island, Museum Construction Site, 2011. More images from the series on Ibraaz

Better quality video at The Guardian

The men constructing the architectural ‘icons’ designed by the likes of Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid (aka the It’s not my duty as an architect to look at it lady) and Tadao Ando, are trapped there since their passports have been confiscated, they receive lower than expected wages, are confined to substandard housing, are submitted to 10pm curfew, poor food as well as segregation in the official labour camp, etc.

Because of the notoriously low wages they receive, migrant labourers often have to work for years before they manage to pay off the debt they contracted to cover the recruitment and travel fees to the UAE. This recruitment debt is central to the system. No one would labor under such conditions unless they had to pay it off.

If they protest against the poor living/working conditions or unpaid wages, the workers get punished or deported.

And anyone who speaks in their favour isn’t welcome in the country…

The editor of the book, Andrew Ross, is a professor of Social and Cultural Analysis at New York University, and a social activist. Earlier this year, he wanted to do some research on labor issues at Abu Dhabi, where a campus of his university is located but he was informed at JFK Airport that he could not enter the country. Similar rebukes awaited other members of the Gulf Labor Coalition. Artist Ashok Sukumaran was denied a visa to travel to the UAE. Walid Raad was turned back at the Dubai airport.

Migrant workers, in their tiny apartment in Abu Dhabi, earn as little as $272 a month while building a campus for New York University. Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Migrant workers, in their tiny apartment in Abu Dhabi, earn as little as $272 a month while building a campus for New York University. Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Laborers nap on pieces of empty cardboard boxes during their midday break at the Dragon Mart Phase 2 construction site in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Photo AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili (The Associated Press), via ABQJournal

Laborers nap on pieces of empty cardboard boxes during their midday break at the Dragon Mart Phase 2 construction site in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Photo AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili (The Associated Press), via ABQJournal

The artist group Gulf Labor Coalition has spent the past few years investigating and denouncing migrant worker abuse. But while the UAE and other Gulf governments can largely ignore the group’s calls, the European and American cultural institutions who will be present on Saadiyat Island need to protect their ‘brand’ and the values they stand for. As Paula Chakravartty and Nitasha Dhillon write in their essay for the book: it remains urgent to continue to use our leverage as artists and scholars to hold US and European museums and universities accountable in their home countries for the abuses against human dignity of workers thousands of miles away.

The Gulf. High Culture/Hard Labor charters Gulf Labor’s fight in a series of texts written by members of the coalition.

Some of the authors explore Western institutions complicity in migrant worker abuse on Saadiyat, other analyse the place of construction workers in the building process, report on visits and interviews with deported workers, look at the artists who have engaged in direct political action, draw lessons from examples of art and activism in the global stage, document performances organised inside the Guggenheim Museum in New York by G.U.L.F. (Global Ultra Luxury Faction, a ‘Gulf Labor spinoff devoted to direct action’ Global Ultra Luxury Faction, etc.

Guggenheim petro-dollars rain down, March 2014. Image Hyperallergic

Guggenheim petro-dollars rain down, March 2014. Image Hyperallergic

The Gulf. High Culture/Hard Labor is lively, opinionated and eye-opening book. It is an important publication because of the realities it reveals and investigates. But it does more than that. The essays it contains can be read as a series of lessons for anyone, journalists, artists or activists, who want to take a stand, protest and challenge every complicit element leading to a situation of abuse and injustice.

Because things might be slow to change but that doesn’t mean protesting is useless. As Sarah Leah Whitson notes in the foreword:

The efforts of Gulf Labor have prevented these world-class institutions from sweeping their complicity in the exploitation of migrant workers under Abu Dhabi’s desert sands.

Most significantly, these efforts have produced concrete results, with the private institutions and businesses involved in Saadiyat Island agreeing to a minimum set of commitments to protect worker rights, including the right to change jobs, an end to passport confiscation, and the refunding of recruiting fees.

And the campaign has even led the UAE grudgingly to adopt some legislative reforms, including electronic payment of wages, changes to the sponsorship system that allow workers to switch jobs under limited circumstances, and greater supervision of work conditions by a vastly expanded pool of government inspectors.

Migrant workers from Bangladesh in the apartment in Abu Dhabi that they share. The labor force on N.Y.U.’s new campus numbered 6,000 at its peak. Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Migrant workers from Bangladesh in the apartment in Abu Dhabi that they share. The labor force on N.Y.U.’s new campus numbered 6,000 at its peak. Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Shift labourers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi. ©Samer Muscati, 2011. Via Blouin art info

Shift labourers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi. ©Samer Muscati, 2011. Via Blouin art info

By the way, Hyperallergic is doing a great job at keeping up with Gulf Labor latest actions.