Rural areas are in crisis in many parts of the world. In Europe for example, an increasing number of villages and small towns are slowly dying. The demographic decline is due in part of an ageing population and in part to the departure of young people looking for job opportunities in big cities.

We like to think that we care about the countryside. We have an idyllic vision of rural areas as blissful and honest places, as the last (albeit often imaginary) refuges of venerable values. Yet, if we don’t engage in more meaningful ways with rural communities, they might become little more than national parks, totally disconnected from the economy, the politics and the culture of the rest of a country.

Philip Samartzis at Pollinaria / A Futurist’s Cookbook, Campo Imperatore, Abruzzo, Italy, June 2017. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

A curator, writer, researcher and man of many talents*, Leandro Pisano has a much more informed and ultimately more optimistic view than I do on the current state of rural communities and on their future. Together with independent researcher Beatrice Ferrara, Pisano has been looking for more empowering and more dynamic futures for rural areas. The duo has been investigating ways to use culture -and in particular sound art and technocultures- to better understand the complexity of rural areas and to challenge discourses of capitalism that tend to marginalise these rural territories.

Drawing on extensive research in rural areas and on their experience of organising cultural events and conversations in small towns across Southern Italy and beyond, Ferrara and Pisano have written a Manifesto of Rural Futurism (PDF.)

“The Manifesto of Rural Futurism,” they write, “is a transnational project interrogating current discourses on rurality as authentic, utopic, anachronistic, provincial, traditional and stable, and the binaries that support such discourses: belonging vs. alienation, development vs. backwardness.”

The title of the project refers less to Marinetti‘s Manifesto of Futurism than to postcolonial futurisms such as Afrofuturism which envisions a future in which arts, science and technology encounter ancient African traditions and black identity to create new narratives of resistance.

Yasuhiro Morinaga at Irpinia Field Works – Conza della Campania, Irpinia, South Italy, May 2011. Photo Leandro Pisano

Sarah Waring at Liminaria 2018. Photo: Speranza De Nicola

I’ve been admiring Pisano’s work for a number of years. I even had the chance to attend one of the digital and sound art festivals he organised back in 2012 in Tufo, a tiny town in the province of Avellino, Campania, southern Italy. I recently caught up with him to chat about The Manifesto’s critical approach to rurality.

Hi Leandro! You’ve presented the Manifesto in several countries. Italy of course but also South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. Does the Manifesto resonate differently in each country and culture? Or do you find that despite a series of superficial differences, all rural communities are suffering from the same problems and asking themselves the same questions?

On one hand, it’s clear that in the Anthropocene, in the era of conflicting coexistences, it doesn’t make much sense to raise the question of the distinction between urban and rural dimension in a topographical, geographical or territorial sense. Rather, the idea of rurality is articulated around the concept of limit, of border, feeding on a series of tensions between different elements: authenticity and utopia, anachronism and provincialism, tradition and sense of stability, belonging and estrangement. In this sense, rurality itself emerges as a political position, in a perspective that relocates it to the flow of modernity as a removed, subaltern or even rejected element, avoiding a nostalgic or “museified” representation.

On the other hand, on a local level, the rural has to come to terms with specific and complex dynamics between local territory and urban space, such as the issues of ‘generation’ and ‘time’ within local communities (depopulation, movement and cultural heritage), the peculiar geophysical characteristics of the place (remoteness, wind, energy, infrastructure and/or lack thereof), the relation between local context and global changes generated by the multidimensional challenges associated with the Anthropocene (climate, lithosphere, biosphere and the planet’s chemistry). During the years, we experimented with this diversity and multiplicity in different parts of the world, where a series of specific issues emerged in the rural areas we have crossed, such as the sudden hyper-urbanization of the former countryside areas in the suburb area of Seoul, the extreme remoteness in Australia, the extensive landlordism in Brazil and the legacy of colonisation in New Zealand.

Jo Burzynska doing field recordings in Torrecuso, Risonanze di Vino 2018. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Ilaria Gadenz at Liminaria 2016 – Rural Futurism, Montefalcone di Valfortore, Fortore, South Italy, july 2016. Photo Leandro Pisano

The Manifesto is a result of a several years’ long research and conversation you had with artists and theorists, but also with rural communities. How did you engage them into the reflection?

Since the first years of our work, our curatorial strategy has often included very long phases of dialogue and preliminary preparation with the artists, oriented towards sharing the approach and methods of the projects. Our idea has always been to create the conditions for realizing an experience geared towards mutual knowledge and fair exchange with local communities. In this way, it has been possible to define a constant process of creative approaches with respect to the territories in which we operated. At the same time, the attention of the artists to the complexity and plurality of ideas generated by the processes of listening, in a critical sense, have produced specific areas of investigation, intersection, and interaction in reference to the themes that involve local communities: the concept of ‘identity’, the approach to abandoned places, to ‘nature’ and the impact of technologies on landscapes.

What emerged strongly – during the process of analysis and curatorial reflection on the different researches and works carried out by the artists year after year – was that the territory itself increasingly claimed its active presence in the research process, freeing itself from the passive position of ‘landscape to describe’. In terms of sound research, what has happened is that, progressively, the projects created by the artists have increasingly been characterized both by the emphasis placed on the composition beyond the documentation and by an approach of immersiveness with respect to the community dynamics inside which their work was founded.

In this context, a series of processes have been put in place that have opened spaces of interaction between communities and artists based on shared interests, even temporarily, or simply built on the encounter that occurs by chance, determined by living in the same way and place and the same time. It is clear that in the context of this encounter, which produces something unexpected, the most intense experiences were those in which the conditions were created – often in unpredictable ways – for experimenting in a shared and horizontal way, in the relationship between the artist and the local community, the recombination of elements, practices, and possibilities already in circulation in the territory, where the intervention of the artists does not represent a force that comes from outside, but represents an action in a cultural space in which it becomes possible to imagine and practice a different political economy.

A Soundwalk — Liminaria 2018

I’m also curious about the type of feedback you received from people of different generations? Do young people living in rural areas have radically different perceptions and hopes about rurality?

What we have often found during our work in different rural areas of South Italy is the desire to recover – above all from the younger generations – awareness of the resources that the rural territories possess, even if they often appear invisible. In fact, these resources are at hand on the territories and must be activated and recovered. It is an idea that is increasingly taking hold in some of these territories and is expressed by the work of those who were born in the rural areas, then trained and studied in metropolitan contexts, and subsequently decided to return to the territories of origin to apply their skills locally.

All of this contributes to reversing the process whereby those who return to their territory of origin, after an experience in the city, feel the weight of a failure. On the contrary, this return can become a real value for young people in rural areas of Italy and not the obvious mark of those who have not been successful. It contributes to the activation of a virtuous path by young people who move away from rural areas: they acquire knowledge in the metropolitan area and return to reinvest and enrich their territory on different levels, fueling the process that the anthropologist Vito Teti defines as ‘restanza’, the return to and / or choice to remain in the area. We have collected various stories which tell of escape and subsequent ‘resettlement’ and that are often the fruit as well as the deployment of a continuous and mutual hybridisation of knowledge between the urban and the rural. If there is a perceived and real risk of the rural regions losing various aspects of their intangible heritage, important stories of ‘restanza’, which clearly express the resilience underpinning the depopulation process, are immediately worth highlighting.

Emanuele Errante at In Limina Orbis – Solfatara di Pozzuoli, Phlegraean Fields, South Italy, April 2012. Photo: Leandro Pisano

A member of the audience listening to the Gunhild Mathea Olaussen + Helene Førde sound installation at Liminaria 2017 – Coexistences, Montefalcone di Valfortore, Fortore, South Italy, July 2016. Photo: Gunhild Mathea Olaussen

On the other hand, I suspect that engaging people who have always lived in urban areas might require a different approach. Why should they care about rurality after all? It often look so distant, both geographically and culturally?

I think that the profound climate changes and transformations in the relationship between humans and non-humans that we are witnessing directly in the contemporary era raise a series of urgent questions also for those who are geographically and culturally distant from rural territories. These areas represent a fundamental safeguard with respect to the processes of food and energy production, environmental recycling, and sustainability; also with regard to the landscape. This issue has deeply influenced our curatorial strategy that has been built over the years, adopting and exercising a self-reflexive perspective with an ‘ecological’ or ‘ecosophic’ focus in relation to place, movement and difference.

In the specific case of our residences in rural spaces, the possibilities for relocating art beyond the white cube have encouraged artists to experience different geographies and spaces. This bi-directional movement, back and forth from an urban to a ‘remote’ or peripheral environment, has produced an artistic practice enhanced by the dialectic of movement and difference. The idea was to challenge artists to question their social ‘self-representation’ in the urban context and reconnect with an environment far beyond that which feeds their daily practice, allowing them to finally renegotiate the terms of artistic production and knowledge through the possibility of new relationships and multicultural debate.

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne in Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

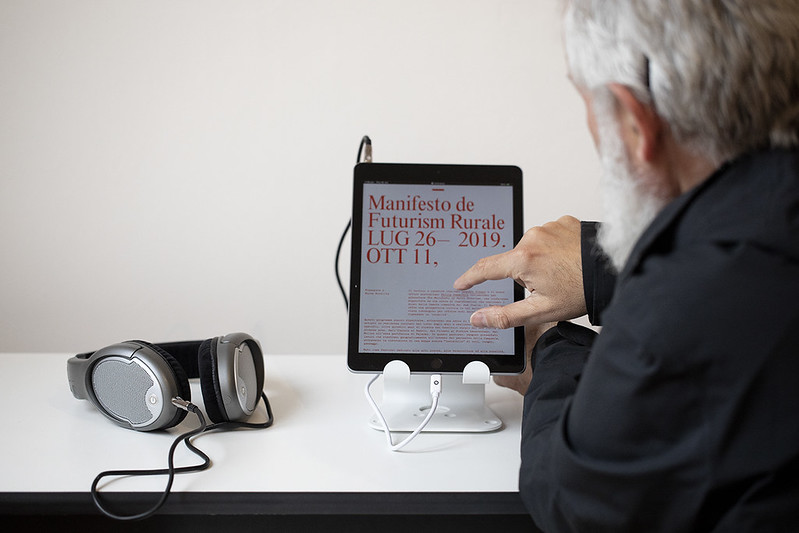

Manifesto of Rural Futurism. Italian Institute of Culture Melbourne, 26 July – 11 October 2019

The Manifesto was accompanied by an exhibition in Melbourne. Could you take us through a couple of the artworks exhibited there? And tell us how they relate to the theme of the future of rurality?

The exhibition held in Melbourne comprises sound and visual recordings undertaken by almost twenty artists involved in fieldwork in Southern Italy during three different residency programmes: Interferenze new arts festival, Liminaria and Pollinaria. The idea on which it was based is that artistic practices – by interrogating our relationship to memory and the archives of the past – reinserts the concept of the ‘rural’ into the framework of contemporary narratives, deconstructing those discourses that relegate it to the status of a mere residue of wider political, economic, and cultural processes, spanning a global scale. In this way, rural areas become places of experimentation, performativity, critical investigation and change, where it is possible to create future scenarios, starting from the assemblage of the seen and the unseen, of human and non-human elements – objects, materials, speech, relational infrastructures, and technologies that give form to (and are formed as) specific modes of governance.

Among the works exhibited, I would mention as two examples: Philip Samartzis’ “Perpetual Motion” and Jo Burzynska’s “Vallisassoli – New and Ancient Resonances”.

Philip Samartzis and Leandro Pisano at Liminaria 2017 – Coexistences, San Marco dei Cavoti, Fortore, South Italy, june 2017. Photo: Luciana Berti

Philip Samartzis at Liminaria 2017 – Coexistences, San Marco dei Cavoti, Fortore, South Italy, June 2017. Photo: Leandro Pisano

The first sonic piece refers to the field recordings taken by Philip Samartzis during the 2017 edition of Liminaria, in the area of Mount San Marco (1007 m asl), located on the Campanian Apennines in an equidistant position between the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Adriatic Sea. To a deep listening, the seemingly silent landscape of the track reveals a stratification that highlights the traces of a series of recent conflicts among its folds. The repetitive, hypnotic sound of the wind turbines scattered like wildfire on the territory of the Fortore area, whose rotating blades cut the air like rhythmic blows of immense swords, allows a series of political, cultural and economic tensions to emerge. They materialize through the possibilities of listening, to know and live in the world, to relate to the politics of language and with disparate environments, territories and geographies. In its ineffability and in its materiality, these sounds invite us to approach environments, spaces and landscapes, revealing the territorial conflicts and transformations that affect the ideological, infrastructural and biological ecosystems of which we are part.

The second piece, “Vallisassoli – New and Ancient Resonances”, is an audio track presented by sound artist and wine writer Jo Burzynska which analyzes the interactions between sound, wine, culture, and the senses across different areas of oenological production (namely, Monte Taburno and Valle Caudina) in inland Campania. The results of this exploration later guided the actual process of recording, which took place in vineyards and wine cellars. This site-specific soundscape was recorded from a 300-year-old vineyard in the village of San Martino Valle Caudina, where I live. As the author has written, “Perceptually [the sonic piece] has a bright tone, purity and richness to the sound that correspond with the flavours of the wine. In between the bells, crickets and insects sing in the living, organic Vallisassoli vineyards, which work with the freshness of the wine, as does the high pitch of the fermenting wine that’s also part of this work. The bells both symbolise the old winegrowing tradition and herald the new.”

Through the listening experience, both works reveal the rural environment as a space of resonance and dissonance, a complex assemblage of visible and invisible forces, of memories and technologies, of ecologies and tensions, introducing the stimulus of critically rethinking about material processes of economy, landscape and territorial policies.

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Istituto Italiano di Cultura – Italian Cultural Institute Melbourne, July 2019. Photo: Daniela D’Arielli

I’m also very curious about your choice of artworks that use technology in order to explore and communicate rurality. Why bring technology to one of the last few places where the experience doesn’t seem to be entirely mediated by technology?

Sincerely, I think that the idea that rural places are among the ones where the experience doesn’t seem to be entirely mediated by technology is in a certain way behind us. Among the many consequences that the phenomena of globalization have had is that even rural areas are projections of urban reality since they, not only in Italy and Europe, but also in the global South, are aligned with a series of languages that we are accustomed to considering proper to urban cultures, such as digital, but going further back we say the same about ‘old’ technologies or media such as TV, telephones and so on.

Specifically, our approach is inspired by the idea of intersecting rural culture with technology with the aim of turning marginal and rural territories, which are considered invisible or destined to disappear in the discourses of modernism and contemporary capitalism, into spaces and places of action and imagination of possible futures.

In this sense, the Manifesto of Rural Futurism, rather than referring to Italian Futurism, with which it, however, shares an irreverent and also ironic approach, is directly connected – in a conceptual and practical sense – to the ‘minor’ futurisms of the postcolonial sphere, such as Afro-futurism, in which technologies become tools of awareness and resistance to affirm a series of counter-narratives in relation to positions of inequality and difference.

Landscape, Palermo. Liminaria 2018 / Manifesta 12 – Transitions, Palermo, South Italy, November 2018. Photo: Giuliano Mozzillo

Liminaria 2016. Photo: Andrea Cocca

The Manifesto relies on the extensive experience you had with the Liminaria festival (and Interferenze before that) in which you bring artists to remote areas in Southern Italy to engage with landscapes and cultures. How do the artists and local communities relate to each other?

Artists who’ve participated since 2014 in Liminaria’s micro residency programme have creatively approached local territory, analysing and re-narrating the region’s characters — the complex dynamics between rural and urban space, building community over time, its geophysical characteristics — via an experience oriented towards combined knowledge and mutual exchange with local communities, who are invited to speak directly with artists. Rather than interpreting issues and circumstances of local and global significance in overtly ‘simple’ terms, it soon became clear in local territory that standard means of reading rurality, based on oppositions between ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’, ‘city worker’ and ‘farmer’, hardly withstand scrutiny.

Focussing on a local area defined by its own confines – the Fortore rural area, on the border of three regions in South Italy: Campania, Molise and Puglia – over several consecutive years has allowed Liminaria’s working group an undeniable privilege. The time to pose and receive questions — which, at times, may be awkward — about the meaning and sustainability of working protocols for projects involving artistic interventions such as Liminaria touch on sensitive issues. Approaching notions of ‘community’ and its (self)representation runs the risk of objectification from the outset; in addition, care also needs to be taken to avoid raising expectations within the social fabric where the project operates by recognising the collaborative and autonomous nature of relationships that might otherwise risk doing more harm than good.

Due to Liminaria’s time constraints, the project has developed in intensity rather than extent with the number of public presentations incrementally — and perhaps paradoxically — being reduced during each week-long event organised two or three times a year. Time and human energy in combination reflect important issues regarding the sustainability of what can be produced, particularly in terms of independent research: for the curators it therefore seemed worthwhile to invest more in the micro residences as, in terms of interventions, they encompass the most important and involved interaction between the project itself and its premise, team, region, artists and all of those who are locally involved in the process.

Any upcoming work, event or field of research you could share with us?

After the first five-year cycle of Liminaria, around which we had built the entire project, originally focused specifically on the Fortore area, we are now in a phase of rethinking the possibility of continuing it and any methods of transformation of the project itself. We are reflecting on a series of actions to be planned for 2020 in different territories and on an overall reconfiguration that could be a prelude to a new phase in our research. After the Manifesto of Rural Futurism exhibition that I curated together with Philip Samartzis and which recently closed at the Italian Cultural Institute in Melbourne, we would like to re-propose the works presented in Australia also in other contexts, including in the Mediterranean area. At the same time, we will continue to work on the connections that we have developed in recent years in Latin America, through an exhibition to take place in Italy and that will be the result of cooperation with the Encuentro Lumen festival and Ultima Esperanza artist group in Chilean Patagonia and a book on Southern American sound art on which I am working.

Thanks Leandro!

*Leandro Pisano is a curator, writer and independent researcher who is particularly interested in the political ecology of rural, marginal and remote territories. He has curated several sonic arts exhibitions across the world and is the founder and director of Interferenze new arts festival and is frequently involved in projects on electronic and sound art, including Mediaterrae Vol.1, Barsento Mediascape and Liminaria.

He is author of the book Nuove geografie del suono. Spazi e territori nell’epoca postdigitale (“New geographies of sound. Spaces and territories in post-digital time”.)

Pisano holds a PhD in Cultural and Post-Colonial Studies from University of Naples “L’Orientale”, where he is a member of Center for Postcolonial and Gender Studies. He is an Honorary Scientific Fellow in Anglo-American Literature at University of Urbino “Carlo Bo”. And if all the above were not enough, he is also teaching Ancient Greek, Latin and Italian Literature in Italian secondary schools.