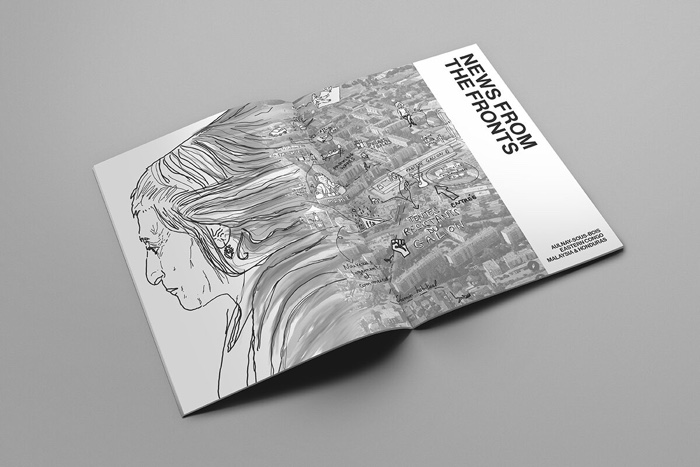

For its 60th issue (happy 10th anniversary, The Funambulist!), one of my favourite magazines is commemorating the 80th anniversary of the US nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

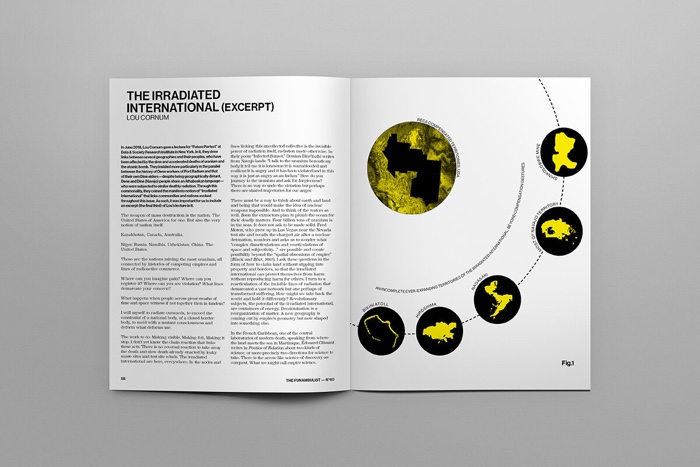

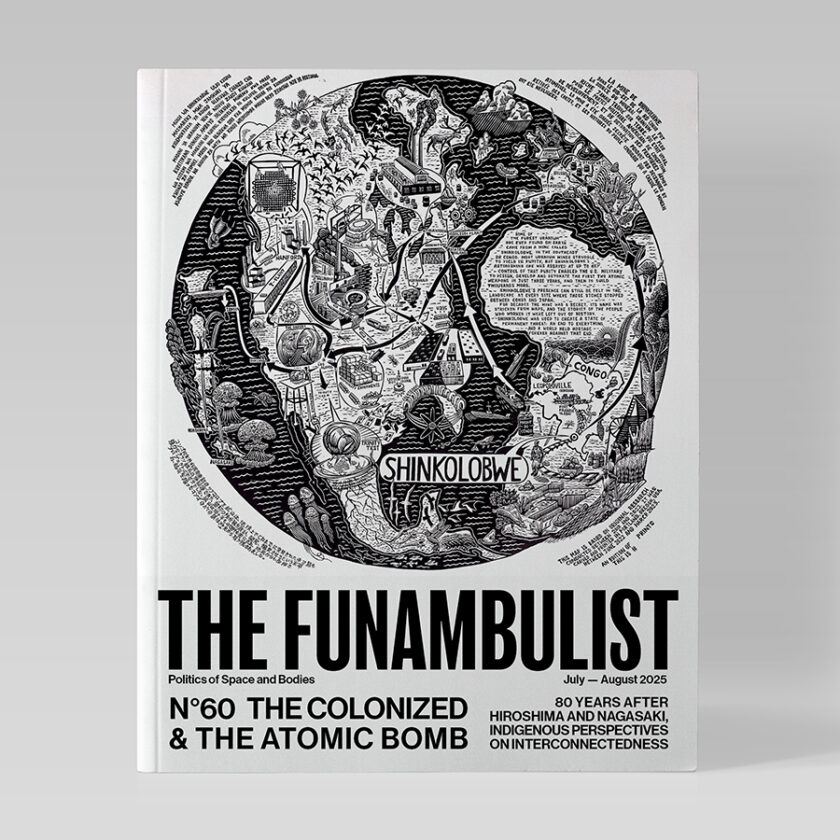

Titled The Colonized & the Atomic Bomb, the issue brings together lands and communities that, albeit distant from each other on the map, have all been affected by a series of abuses which “culminated” in the nuclear bombings of the two Japanese cities. The stories of injustice, plunder and imperialism told by the activists, academics and artists who contributed to this issue are hard to stomach. More often than not, however, these stories also come with the awareness of an interconnectedness that paves the way for circuits of solidarity, kinship and resistance. Or what Lou Cornum calls an “Irradiated International”. In an excerpt of their Manifesto of the same name, Cornum explains that:

“We must think outside the community. Outside the limits of what you can care for. Imagine a solidarity that does not have to be solid. But diffuse. As widespread and impersonal as violence, as radiation.”

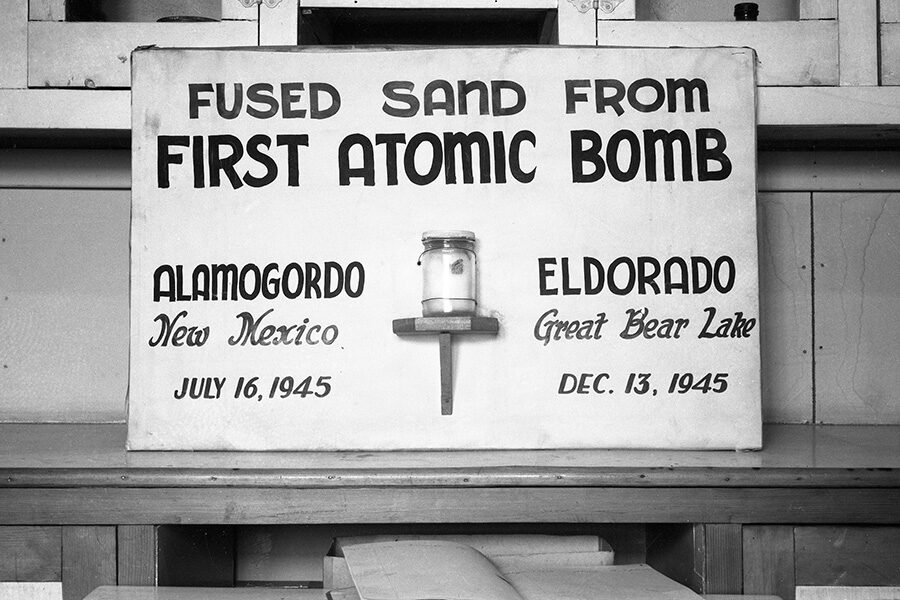

One of the stories that best embodies this complex network of relations between distant nations and territories is told by Glen Sean Coulthard, from the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, in Dene Country (what Canada designates as Northwest Territories.) In his essay, the scholar of Indigenous studies explains the part that Dene people unwillingly played in the bombing of Hiroshima. During the Manhattan Project, Dene labourers were employed to transport and handle uranium ore from Port Radium on Dene land without adequate protective gear, knowledge of the potential health risks or even inkling of what the radioactive material was going to be used for.

Feeling guilt and grief, not only for their own loss but for the loss of tens of thousands of lives of people in Japan, the Dene sent a delegation to Hiroshima in August of 1998 to apologise for the role they had played in the development of the bombs dropped on their city.

Sammy Baloji, Shinkolobwe’s Abstraction, 2022. Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès

A sign with a jar of ‘fused sand from first atomic bomb; Alamogordo, New Mexico, July 16, 1945; Eldorado, Great Bear Lake, December 13, 1945’ on display in Port Radium. Photo from Canada’s Northwest Territories Archives

The magazine also features a conversation between Jennifer Marley and Sabu Kohso about the forms of resistance against colonial nuclearism by Tewa pueblos (whose land was stolen to build the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos National Laboratory) and activists in Japan.

While Kohso examines how Japanese women (popularly referred to as “enraged mothers”) and other ordinary citizens who defend their land are at the origins of many anti-nuclear initiatives, Marley looks at how the Native people and the Nuevo Mexicanos have been exploited by the US since the early days of the Manhattan Project. At the time, these communities were still living off the land that they communally owned. The US government took their hunting grounds, divided their farmland and forced them to abide by private ownership. Then the US military, who needed labour force for Los Alamos, forced these people into the wage economy. They were made to work as maintenance people and domestic labourers for LANL. As if that were not enough, the US also poured the first nuclear waste ever made into their sacred sites and made them inaccessible. Today, there are attempts to reopen uranium mines on Native land throughout the US Southwest for “clean” nuclear energy.

This issue of The Funambulist also insists on an understanding of Japan as a colonial power. Lisa Yoneyama‘s text, for example, looks at the lives of dozens of thousands of colonised Koreans, displaced to Japan under duress, who were killed in the 1945 nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Often forgotten in narrative that describes the victims of the massacres, Korean hibakusha have endured decades of neglect, in line with the ethnic and racialised prejudices that characterised Japan’s colonial policies and ideology.

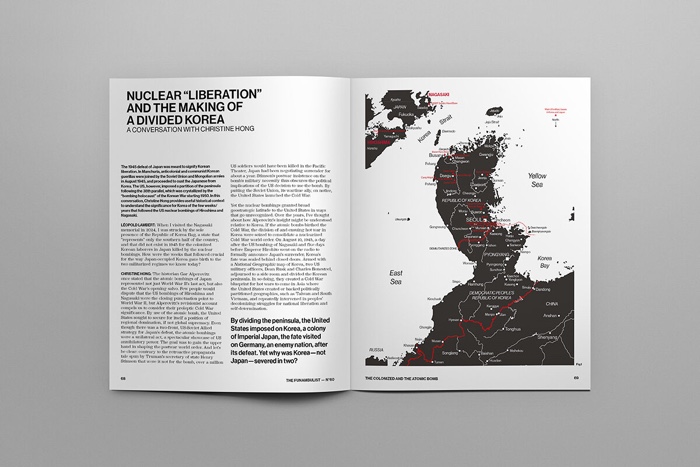

Christine Hong provides a much-needed historical context to the events that followed the US nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Instead of marking the Korean liberation from Japanese colonialism, the bombings led to the US occupation of the southern part of the peninsula, the beginning of the war in 1950, the crystallisation of the separation between North and South and an ongoing military grip on South Korea by the United States.

Kia Quichocho looks at the role that the islands of Tinian and Guåhan played in the 1945 bombings. Not only did the two US military aircrafts took off from there when they dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but in the two decades that followed, the US military “tested” nuclear weapons in Micronesia. As a result, people in Guåhan, who at the time were majority indigenous Chamoru, became downwinders. Although this exposure and the deadly health complications for Indigenous people of the region have been proven, Guåhan remains uncompensated and unrecognised by the federal government under the US Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

As Quichocho concludes, “These micro-level realities often sit in the periphery of world powers as they justify their politically-driven military agendas. However, the wind that carries nuclear fallout does not distinguish between the rulers and the ruled.”

Operation“SailorHat,”1965.Detonation of the 500-tonTNT explosive charge for Shot “Bravo,” first of a series of three test explosions on the southwestern tip of Kaho’olawe, on February 6, 1965. Weapons effects test ship Atlanta (IX-304) is moored in the left center. / US Navy, public domain. Via wikipedia

In his beautiful essay, Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio describes the US invasion, the brutal and ecocidal militarisation of Hawaiʻi and the role the kingdom was forced to play during the Pacific War. While Hawaiʻi never attacked another country as a modern state, the islands form one of the largest platforms in the world for American military interventions. The US’s ongoing use of the islands for training and target practice is the source of resentment and resistance but it has also given way to a feeling of interconnectedness with other people around the world who, to this day, continue to be affected by US imperialism.

In 2022, Roger Peet created the map that graces the cover of The Funambulist. Dig Up the Sun maps the connections between the US nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Euro-American colonialism and extractivim in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The drawing commemorates the sacrifice of the nameless Congolese workers who worked in the mines of Shinkolobwe, which were the source of the highly concentrated radioactive material used to design, develop, test and detonate the first atomic bombs.

I’m actually a bit late with this review. The new issue of the magazine, Ten Years of The Funambulist, was published a few days ago. I’m going to download and read it but in the meantime, i’m leaving you with spreads from The Colonized & the Atomic Bomb: