Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg is a designer, artist and researcher. I first met her while she was finishing her MA in Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art last Summer. The work she was exhibiting at the final show, The Synthetic Kingdom, explored how design could contribute to a field that most of us find a bit intimidating and distant from our daily preoccupations: synthetic biology.

Among Daisy’s latest activities are a residency she recently completed at SymbioticA, a collaboration with James King and Cambridge University’s iGEM 2009 grand-prizewinning team and then there’s Synthetic Aesthetics. This project investigates shared territory between design and synthetic biology, invites exchange of existing skills and approaches, and makes possible the development of new forms of craft and collaboration. Synthetic Aesthetics is now offering 12 residencies as 6 exchanges anywhere in the world, exploring what design and art have to offer to synthetic biology, and the other way round…

And because Daisy and i agree that the residencies shouldn’t be left solely in the hands of the usual suspects (i.e. the RCA alumni), i asked her to give us more details about Synthetic Aesthetics.

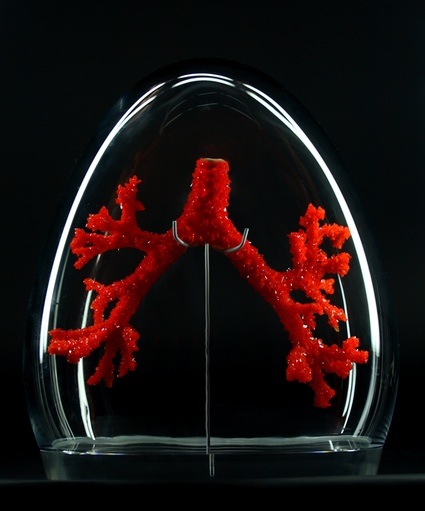

Pollution-Sensing lung tumor from Daisy Ginsberg’s project Synthetic Kingdom

Pollution-Sensing lung tumor from Daisy Ginsberg’s project Synthetic Kingdom

Synthetic biology is a bit of a daunting area of research. It seems to be highly technical and almost too abstract. How much background in Synthetic Biology would the designers and artists who apply for the residency need?

Synthetic biology is the application of engineering principles to biology – living matter has become a new material for engineering, a new technology for design and construction. The promise is that we can simplify the way we engineer life, making it predictable and useful (though biology’s complexity still challenges us, for now). The discussions today are creating a framework that could influence biology and nature for generations to come.

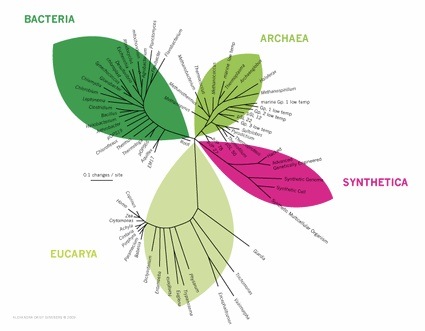

The deeper I get, the more fascinating and complex it becomes and the faster the field is evolving. For the last two years I have been engaging with the construction of this potential future and the ethical implications it presents. My RCA projects, The Synthetic Kingdom – a proposal for a new branch of the Tree of Life – and Growth Assembly, with Sascha Pohflepp, investigate this (both currently on show in the Wellcome Trust‘s windows).

Dunne and Raby, WHAT IF…, window display, 2010. Image Wellcome

Dunne and Raby, WHAT IF…, window display, 2010. Image Wellcome

The principles behind synthetic biology are straightforward: standardization, abstraction and modularity. Synthetic Aesthetics is not looking for designers or artists necessarily expert in genetics, rather, how might design and art work in dialogue with the evolving science? We’re interested in the overlaps between synthetic biology and design, the ways that we can explore and interrogate science, opening up new thought areas and processes. We’re asking: how would you design nature?

Synthetic biology is multi-disciplinary, from computer scientists to mechanical engineers. As design advisor with James King to the 2009 Cambridge University iGEM competition team (International Genetically Engineered Machines), we joined undergraduates in Maths, Physics, Engineering and other subjects in a two-week synbio crash course last July.

After this introduction, the team began designing using synthetic biology. After ten weeks, they had made E.coli that secrete many different colours visible to the naked eye, which we named E.chromi. We experimented with ways design can help science innovate, using design methods of narrative and design workshops to help the team engage with the bigger picture – the social, cultural and ethical consequences of their research. Cambridge went on to win iGEM out of 120 teams and 1500 students!

What are these “embedded residencies” going to be like? Artists and designers will be invited to spend time in labs and scientists in art workshops? What would the outcome of the residency be? A tangible product/project such as “E. chromi: The Scatalog” that you designed with James King?

We want to introduce molecular scientists and engineers to creative design processes, while inducting artists, designers and others to the ideas of rapid prototyping of biology, lab craft, and tools for designing living systems. We’re used to artists going into labs, but not the other way round.

We hope tangible projects come out of the six exchanges; collaborations that extend beyond the four weeks the twelve participants spend in each other’s workspaces. The outcome may be an object, writing, an installation, a protocol, a new kind bacteria or something entirely different that we don’t have a precedent for yet. We hope to exhibit these.

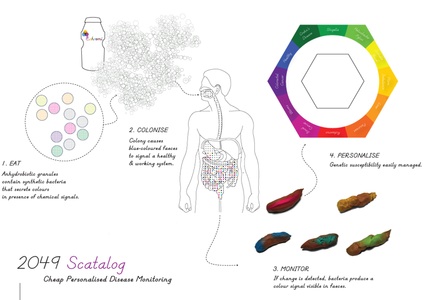

Scatalog: system diagram (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Scatalog: system diagram (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Scatalog: inside of the display case (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Scatalog: inside of the display case (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

The work James and I did with the Cambridge iGEM team hints as to where this might go. Questioning what biological computing might actually look like, we designed the Scatalog, a proposal for cheap, personalized disease monitoring based on the team’s work. In 2049, E.chromi is drunk like Yakult. Though technologically long possible, it is finally culturally acceptable to ingest engineered bacteria. E.chromi live in the gut, quietly monitoring for disease. When they detect something alarming, they secrete a pigment, easily monitored in poo. We took a suitcase – the Scatalog – filled with stool samples to iGEM, asking the people designing these promised technologies to think about what they might actually look like.

(image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

(image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

I’m very interested in the Synthetic Biology protocol you designed for SymbioticA. Can you tell us something about the outcome of your residency there?

The first resident at SymbioticA to work with synthetic biology, I was faced with a challenge. Synthetic biology hasn’t quite hit the University of Western Australia, instead I found myself promoting it to scientists and triggering beginnings. Suddenly, I was a proponent rather than an observer, which was ethically challenging for me. I found a group in Plant Energy Biology doing related research and worked with geneticist Sandra Tanz, learning and assisting with her protocols. While I would describe her work as synbio, she doesn’t as yet. Synthetic biology is the current buzzword, once the hype dies down, hopefully the research will continue.

At SymbioticA, I tried to learn as much molecular biology as possible. After three months in an institutional lab setting – free of the challenges that face DIYbio-ers – could I progress to work on my own scientific research? Could it ever be useful? Can designing wet systems provide greater insight into the issues that synthetic biology presents us? The Cambridge iGEM team made a significant foundational offering in just ten weeks, no longer novices; they are certainly synthetic biologists. As a non-scientist with limited expertise, at what point in the design process can you describe yourself as such?

What is different between this kind of design practice and bio art? Using the term ‘designer’ rather than ‘artist’ brings different responsibility. While it should be possible for me to design a simple system at SymbioticA (and I intend to) I want to better understand its repercussions.

Synthetic Kingdom, The New Tree of Life (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Synthetic Kingdom, The New Tree of Life (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Apart from helping scientists communicate their work, what can design and art do for synthetic biology?

That’s what we want to learn! Synthetic Aesthetics isn’t about public engagement or trying to make synthetic biology acceptable, rather to explore what synthetic biology can be. By adding the human-scale expertise of designers and artists to molecular scale science, can collaborations inform and shape a developing field?

Growth Assembly (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Growth Assembly (image courtesy Daisy Ginsberg)

Growth Assembly, the project that you developed together with Sascha Pohflepp, seems like a far-fetch idea. yet, it is inspired by scientific research. Can you tell us something about the theory and research behind it?

We were thinking about manufacturing post oil crisis and what synthetic biology might offer this future. Jim Haseloff at Cambridge University works with plants, not bacteria, researching morphogenesis – the way plants grow – with the aim of one day controlling it. He suggested that, “one day we may be able to grow products inside plants.”

We started to think how softness and diversity may change the way we understand manufacturing and industrial standards. We sent a call out for illustrators to draw a plant from the future, and luckily found Sion Ap Tomas, new to botanical illustrations, whose interpretation inspired us. Many interesting discussions ensued, keeping in mind Jim’s comments about gravity, cell differentiation and plant morphology!

While far future, it is interesting to see synthetic biologists using our fiction of an herbicide sprayer grown and assembled from seven plants (intended to protect this new, engineered nature) to illustrate their hopes for the field.

Thanks Daisy!

The deadline to submit your application documents for the Synthetic Aesthetic residencies (6 artists/designers, 6 scientists/engineers) is 31st March 2010.