It’s easy to be a future-phobic these days. It’s easy to be anxious, dubious, critical about what tomorrow will bring. Unfortunately, it’s less easy to ignore the future and pretend we don’t care. The future is, as we know, already here with its cohort of mass extinction, private armies, state surveillance and climate disasters. But is that all there is to the future?

Entrance of the STRP festival. Design by HeyHeyDeHaas. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann for STRP

Quayola, Promenade. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer for STRP

This year’s edition of the STRP festival in Eindhoven decided to look at the future with an open, critical and -dare i say- hopeful eye. Their take on the future is not about being naive and resolutely utopian. It’s more subtle than that. It’s about realizing that being stifled by fear is what leaves us in the hands of powerful corporations, far right politicians and other merchants of solutions too rosy and simple to be credible.

As STRP writes in their statement:

We refuse to flee in a crippling nostalgia. We have had enough of the dark and tough flirt with dystopia and ask ourselves out loud: how in heaven’s name can we come through this conservative and fear-driven period together?

This year, the STRP festival looked for inspiration in artistic experiments that evoke the possibility of a more nuanced future. The participating artists never promised to have all the answers but at least they broaden the questions and perspectives.

I’ll come back later with a report on the STRP conference. In the meantime, here’s my quick tour of some of the artworks i particularly enjoyed in the exhibition this year:

Mike Mills, A Mind Forever Voyaging Through Strange Seas of Thought Alone (excerpt), 2014

Mike Mills interviewed about a dozen children of people who work at Silicon Valley. Some of these parents are engineers, others work at a Google cafeteria.

Aged eight to twelve, these children are the ones who will actually be inhabiting the future that the Silicon Valley is selling to us.

First, the filmmaker asks them to speak briefly about themselves. That’s as charming as you might expect. Soon, however, Mills casts the children as futurologists. It turns out that when they are asked about what tomorrow will bring, kids can be quite ambivalent. Some look at the future with bright, enthusiastic eyes. Others are disillusioned. Most present a mix of enthusiasm and pessimism. On the one hand, they embrace technology. They play Minecraft and think that because we have access to so much knowledge, we must be smarter than our ancestors. But their vision of tomorrow can be bleak too: we won’t have trees anymore, we’ll get holographic plants instead; people won’t meet each other physically because the machines will mediate all human interactions, there probably won’t be any animal around either.

The whole film is online.

Hannes Wiedemann, Grinders (A North Star 1.0 implant is being inserted into a person’s arm)

Hannes Wiedemann, Grinders (Amanda is receiving a ‘tragus magnet implant’, Tehachapi, CA)

Hannes Wiedemann, Grinders. Exhibition view at STRP. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Hannes Wiedemann, Grinders (Implantation of a ‘tragus magnet implant’ is being performed while others are watching and recording the procedure with their mobile phones. Tehachapi, CA)

Body hackers are decidedly less hesitant about the positive impacts of technology on their life. They call themselves Grinders, implant magnets in their finger to aquire a sixth sense, embed speakers into their ears and attempt to get closer to machines in order to simplify their lives.

Hannes Wiedemann met members of this community and documented some of their operations. Since no licensed surgeon would accept to perform these procedures for them, the hackers have to learn how to do it themselves (or to each others). It’s risky and far more gory than the idealised vision of the transhumanist future that Ray Kurzweil and his friends are presenting us with.

What makes their faith in technology so interesting is the way it challenges the future and ethics of body enhancement.

Quayola, Promenade (excerpt)

Quayola, Promenade. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Quayola uses machines to enhance human perception but his approach is far less intrusive than the one adopted by the Grinders. Promenade follows a drone as it is flying over the forests of the Vallée de Joux in Switzerland. The film explores the logic and aesthetics of autonomous vehicles computer-vision systems. These machines scan natural environments, decode and portray them using parameters and perception tools different from the ones a human would use.

The artist conceived this work as another chapter in the long historic tradition of landscape painting. Just like his artistic predecessors, he (or maybe the machine) uses the landscape as a pretext to discover new aesthetic languages.

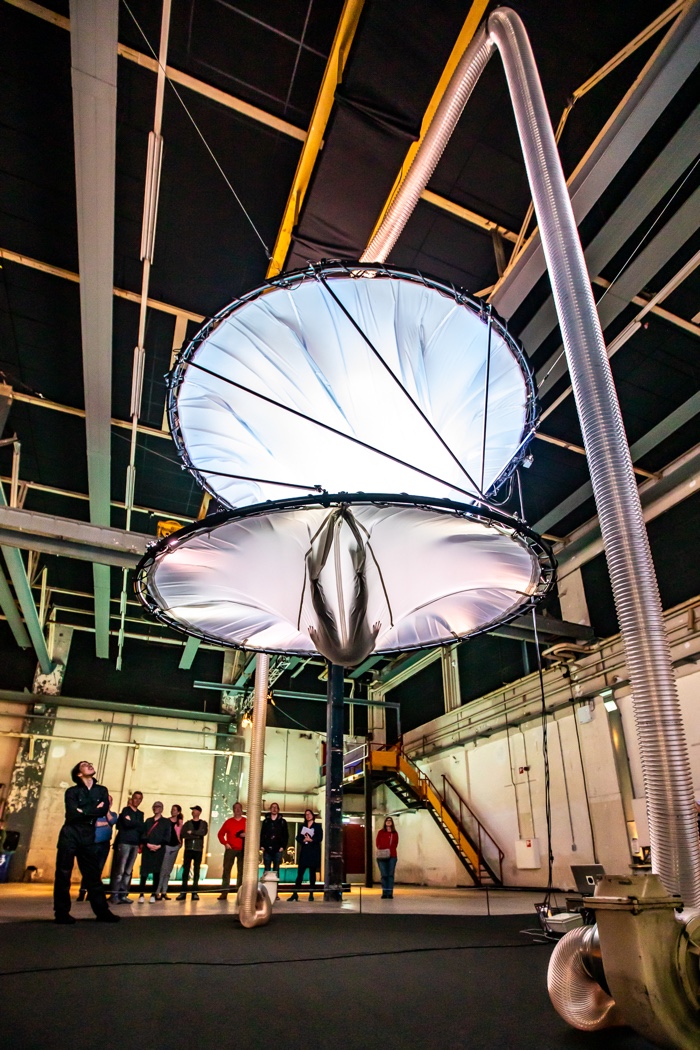

Teun Vonk, A Sense of Gravity, 2019. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Teun Vonk, A Sense of Gravity, 2019. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Teun Vonk wants to make us more aware of the continuous pull of gravity. His immersive installation encloses the visitor (only one at a time) inside a space that challenges their every senses. But it is less about what you feel when you’re suspended in his big soft vessel and more about how you reconnect with your bodily experience once the trip in the floating bubble is over and you’re walking back onto the ‘normal’ space.

The work invites us to reflect on weightlessness and the relevance of human physicality in the future. Will we completely forget about it as our lives become more and more virtual? Will it take another dimension if we ever get to leave this planet and move to some distant celestial body?

Aki Inomata, Why not hand over a ‘shelter’ to hermit crabs?, 2009-ongoing

Aki Inomata, Why not hand over a ‘shelter’ to hermit crabs?, 2009-ongoing. Photo by Juliette Bibasse

Aki Inomata, Why not hand over a ‘shelter’ to hermit crabs?, 2009-ongoing. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Hermit crabs are born with soft, exposed abdomens that leave them vulnerable to predators. They protect their body by squatting empty seashell or hollow pieces of wood they find abandoned on beaches. Increasingly also they adopt the trash that litters our shores. As they grow, they need to move house and find bigger shells.

Aki Inomata creates artificial shells that adapt to the natural shapes of hermit crabs.

Based on CT scans of real hermit crabs’ shells, her 3D-printed habitats feature iconic architectural monuments or even famous cityscapes. The artist then places one of her creations in a tank and waits to see if the small creature will pick up an organic shell or the plastic shelter as its new residency.

The project is delightful and it hints at a future when a new intimacy between the organic and the synthetic will be celebrated (surely we can do better than plastiglomerates and turtles chocking on discarded toys.) However, i wish it showed more compassion to hermits crabs. First, by enclosing them in much bigger tanks. But also by allowing them to enjoy the social life the species is used to.

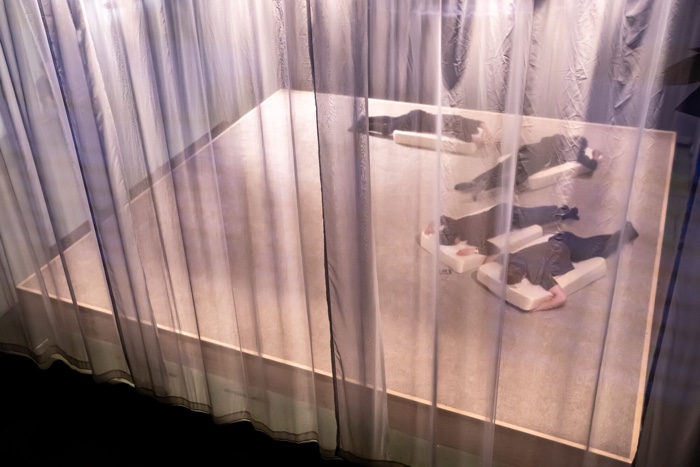

Katja Heitmann, Laboratorium Motus Mori. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Katja Heitmann, Laboratorium Motus Mori. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Katja Heitmann, Laboratorium Motus Mori. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

Over the past few decades, tech companies have quietly been patenting human gestures. Either to prevent competitors from relying on certain physical gestures or to make humans more machine-like.

Choreographer Katja Heitmann has been looking at the other side of this control of our every moves. As technology ‘optimises’ machines and humans and turns them into more ‘efficient’, more compliant tools, could some movements be perceived as superfluous and disappear over time?

Concerned by the possible ‘extinction’ of movements that are part and parcels of our humanity, the artist set up a theatrical laboratory in which she invited the public to donate conscious and unconscious movements. These movements were analysed by dancers and transformed into movement sculptures.

This living exhibition of moribund movements also invited the public to reflect on what makes us humans but might disappear under the pressure of productivity and efficiency.

Merijn Hos in collaboration with Jurriaan Hos, Soft Landing, 2019. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer for STRP

Merijn Hos in collaboration with Jurriaan Hos, Soft Landing, 2019. Photo: Hanneke Wetzer for STRP

Soft Landing is a set of curtains that surrounds your with layers of soft colours as you advance inside the installation towards a large orange ‘sun’. The colour spectrum goes from cold to warm and subtly change in intensity as more people join in. The less visitors are moving inside the space, the more vivid the hues.

HeyHeydeHaas with Désirée Hammen and Pol Tijssen, Exit Through The Flower Shop, 2019. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

HeyHeydeHaas with Désirée Hammen and Pol Tijssen, Exit Through The Flower Shop, 2019. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

HeyHeydeHaas with Désirée Hammen and Pol Tijssen, Exit Through The Flower Shop, 2019. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

To exit the festival, all visitors had to walk through ‘the flower shop’ where they couldn’t buy flowers but they could linger and enjoy their scents, colours and total absence of electronic components. I thought it was a stroke of genius. The flowers almost magically brought visitors back to their basic physical senses and reminded them that some things, like the appreciation of the simple things in life, will never change.

Augmented Reality Tour Billennium with Uninvited Guests & Duncan Spearman. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

Augmented Reality Tour Billennium with Uninvited Guests & Duncan Spearman. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

The ruminations around the future continued outside of the exhibition space….

Only a few decades ago, Strijp-S (where the STRP festival is located) was an industrial park that belonged to electronics company Philips. The area was nicknamed ‘the forbidden city’. Only Philips employees could enter. In the 1990s Philips gradually left Eindhoven and in the early 2000s, the old factories opened up their doors again. This time to artists workshops, design shops and offices for the creative sectors. Uninvited Guests & Duncan Spearman took visitors on a time-traveling guided tour of the Strijp-S area.

The narrative starts with the arrival of Philips in the area, then quickly moves the current hip and design identity of the area. Soon, past and present are discarded and we were invited to move around the area and see the future of Strijp-S.

The “archaeologists of the future” who guided the tour gave us a smartphone and a selfie stick to raise towards the built environment. After a few seconds to allow the AR technology to adjust, future architectures and activities appeared on the screen. We could see and hear the world of Strijp in 2030 and later we could also experience the area in 2090. 2030 was innocent enough. All organic food on balconies, energy-saving public lights, etc. 2090 was downright dystopian and riotous.

The last chapter of the tour was an invitation to imagine and design Strijp’s future. I found myself in the group with the wildest imagination: a volcano would fill the main square in 2060, it would spit cooked sushi for roaming dinosaurs (de-extinct thanks to the wonders of biotech) to feast on. As we were fantasizing about this wild future, it started appearing on our screens. A visual artist was listening to our conversations and drawing our speculations from a nearby office and then streaming it to our devices.

Augmented Reality Tour Billennium managed to materialize a reality that isn’t here yet. It also turned out to be a very entertaining and smart way to engage participants in lively debates about their local context and how it will be affected by the passing of time.

More works and images from the exhibition:

Lauren McCarthy, Waking Agents, 2019. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Lauren McCarthy, Waking Agents, 2019. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

Yann Deval & Marie G. Losseau, Atlas. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

Yann Deval & Marie G. Losseau, Atlas. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

Yann Deval & Marie G. Losseau, Atlas. Photo by Hanneke Wetzer

The STRP exhibition was curated by Gieske Bienert, Juliette Bibasse and Ton van Gool. The next edition of the festival will take place in Eindhoven on 2 to 5 April 2020. But the next Scenario # 3 is already planned for 6 June 2019.