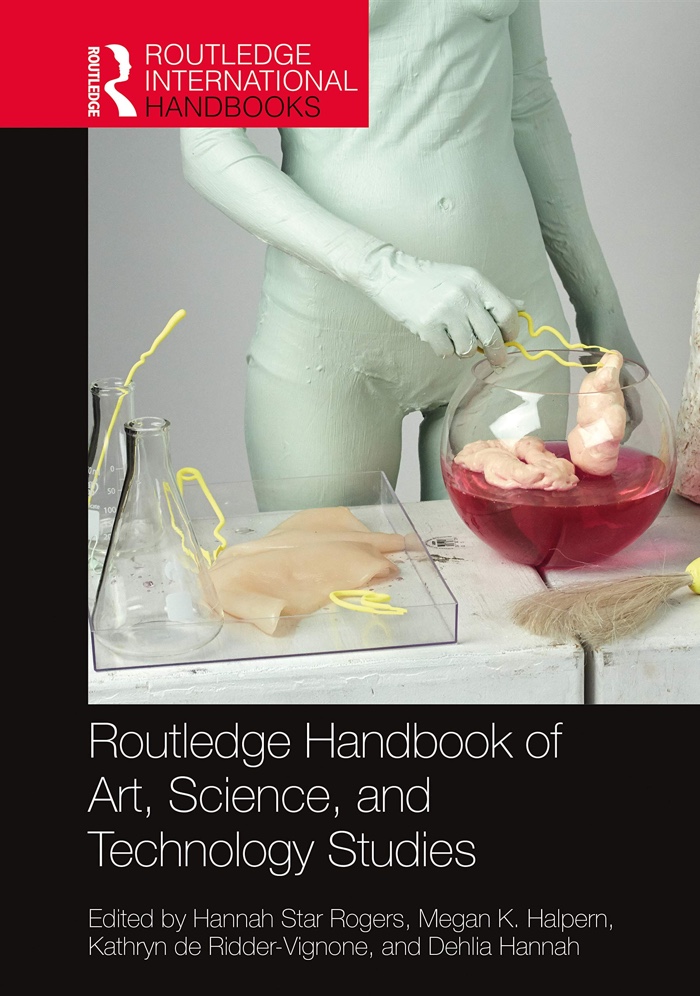

Routledge Handbook of Art, Science, and Technology Studies, edited By Hannah Star Rogers, Megan K Halpern, Dehlia Hannah and Kathryn de Ridder-Vignone.

The book introduces Art, Science and Technology Studies as a new field of interdisciplinary inquiry and practice where both art and science contribute to knowledge-making.

The dozens of essays included in the book examine the methods and methodologies used to bring art and science together, the structures that support these collaborations, the development and communication of projects realised as well as the engagement with the audience.

While several authors in the publication delineate what we can learn from observing art and science in relation to one another, none of them pretends that art-science collaborations are frictionless. Or that they should be. In fact, many of the authors highlight issues such as the institutionalisation of both art and science, the possible instrumentalisation of art, the difficulties encountered while trying to create dialogues with the public around science and technology concerns, etc. Most of them also suggest strategies that artists can adopt to protect their autonomy, find common ground with their science partners and make emerge new forms of critique.

Caitlin Berrigan, Hepatophagy, 2008

David Bowen, fly revolver, 2013

More than fifty authors. Over 650 pages of academic papers. Routledge Handbook of Art, Science, and Technology Studies is a massive volume. I enjoyed the variety of perspectives, the critical viewpoints, the alternatives and strategies suggested over the pages and the many insights into artworks that resulted from collaborations between scientists and artists or designers. As often with this type of academic publication, however, I wish there were more contributions from scholars and artists working outside of the US, the UK and Australia.

Charlotte Jarvis, In Posse: Making Female Sperm, 2018. Photo: Miha Godec

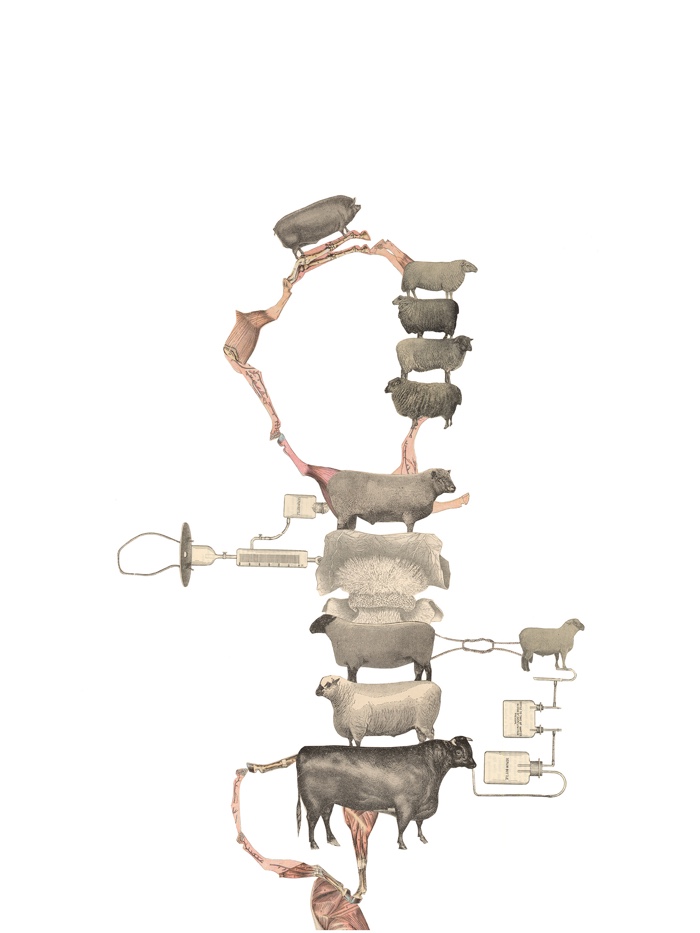

Kirsten Stolle, Animal Pharm (AP5), 2014

Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, untitled (lab shoot series), 2008-2011

Unsurprisingly, the essays written by artists were often the ones I enjoyed the most. Here’s a brief selection of them:

Jennifer Willet narrates how she orchestrated “unruly actions in laboratory environments for cameras and very small audiences of scientists, students, administrators, and cleaning staff.” Together with artist Kira O’Reilly, she performed poetic laboratory actions that had the objectives of subverting the institutional authority of the lab and of exploring conversations between their artistic practices and the interconnections between the human body and the laboratory ecology.

Mary Maggic, Estrofem! Lab. Photo via HOLO

In We’re all living in an Estroworld, Mary Maggic lays down her six-point plan for hormone queering resistance. Operating under what Claire Pentecost calls public amateurism where people consent to learn and fail together in public, she briefly explains how “the knowledge around hormones is not simply contained within scientific methodology but also their biopolitical context, their entanglements with our notions of sex and gender”.

In an “open letter to Lulu and Nana”, Adam Zaretsky writes the famous germline edited twins to raise a series of questions about the consequences of the genetic modification of human beings. By addressing his letter to the little girls, Zaretsky attempts to offer them agency as decision-makers and invites them to consider themselves as art, as a way to understand their GMO identities.

Science and Technology Studies scholar Lea Schick, uses a series of artworks to explore the roles that imagination and speculation can play in outlining future energy strategies.

David Buckley Borden in collaboration with Jack Byers, Aaron Ellison and Salua Rivero, Wayfinding Barrier, No. 3, 2017. Image Credit: © 2018, Aaron M. Ellison; license: CC-BY-NC

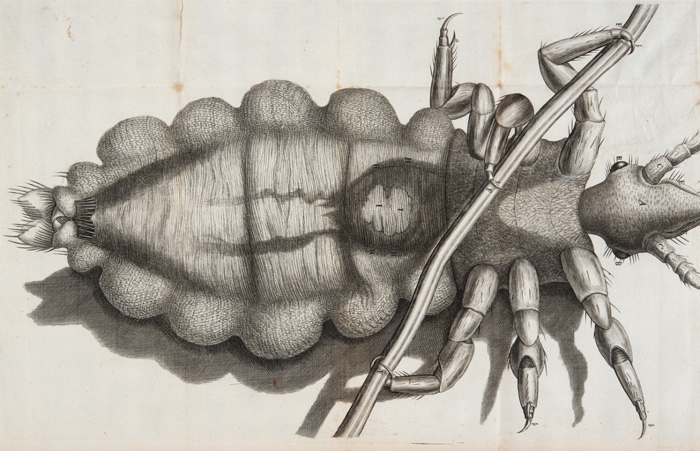

Robert Hooke, Micrographia (a louse), 1665

Ionat Zurr and Oron Catts detail how the wide exposure of their Pig Wings project in media stories and international exhibitions illustrates the promise and the disappointment which underlies the hype that surrounds some scientific discoveries.

Chris Salter‘s tongue-in-cheek history of the relationship between

art, science and technology deconstructs the assumptions we might have regarding art-science collaborations.

Artists and theorists Christian Nold and Karolina Sobecka explore the “aesthetic strategies” that artists can deploy in order to get their voices heard in governance and public policy questions, particularly questions that are often the domain of scientific or technical experts.

.

Nicola Triscott and Anna Santomauro draw on their experiences curating Arts Catalyst to suggest a co-inquiry model that brings diverse groups together around a specific theme or topic while giving them enough leeway to each develop ideas tailored to their respective fields.

Jane Calvert and Pablo Schyfter reflect on their Synthetic Aesthetics experience of orchestrating collaborations between synthetic biologists and artists and designers to consider what STS scholars might learn and what to expect (or not) from working with artists and designers. And vice versa.

Drawing lessons from the production process behind her art/science communication project called Aurator Britt Wray writes about the role of emotion and affect in science communication.

Francis Alÿs, Tornado, Mexico City (Milpa Alta), Mexico, 2010

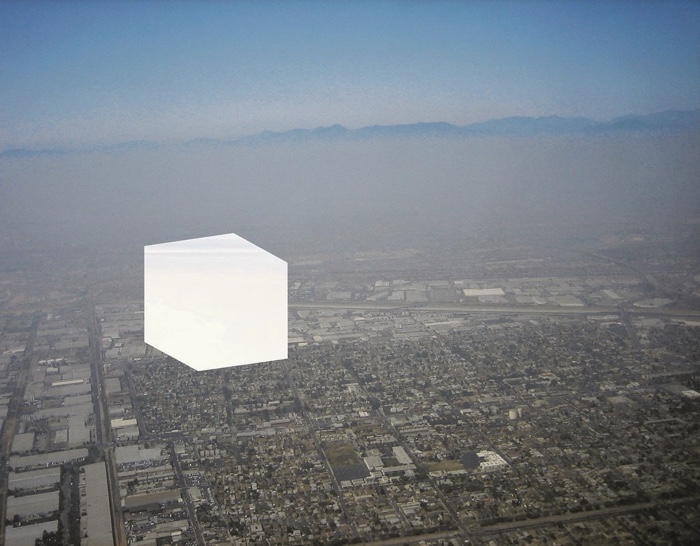

Amy Balkin, Smog over Los Angeles, from the Public Smog project, 2004–

Inspired by Jussi Parikka’s Geology of Media, Brett Zehner explores what he calls the Meteorology of Media and celebrates the storm chaser as an individual whose passion condenses citizen science, risk, improvisation and a bit of art too.

In the Archiving Atmosphere essay, architect and architectural theorist James Graham reviews artistic and architectural projects that engaged with air quality and proposes that the atmosphere itself be understood as an archive marked by historical events and regimes of industrialisation.

Photo on the homepage: Jennifer Willet & Kira O’Reilly.