Last part of my report from that 10 hour long marathon that was Postopolis Day 5 (see previous posts: Postopolis DF – notes from day 5 (first part) and Postopolis DF – 2 activists from Mexico.)

That afternoon we were all very curious to hear what Capitán Remigio Cruz, the curator and guide of the Museo de Enervantes, had to tell us. His presentation wasn’t exactly the one we expected but we did get quite a show. First we got scolded for calling it the Museum of Drugs, its official name is Museo de Enervantes.

Preppy, dynamic Capitán Remigio Cruz came to Postopolis with an agenda. He wasn’t there to show us images of the museum nor did he spend much time commenting on his work as a curator. He was there to educate us about how bad drugs are. Any kind of drug, even marijuana which, the Captain explained, inevitably leads to the use of hard drugs. His statement raised a few eyebrows in the audience. Especially as more voices in the country are calling for the legalization of cannabis.

Nothing these voices could ever argue can dampen the Captain’s enthusiasm for the mission of military authorities. He told us that the army is working extremely hard at fighting drug barons and that their efforts have paid off. According to the World Drug Report of the United Nations, Mexico is no longer the number 1 producer of marijuana. The U.S. have beaten up to the top spot.

I was a bit frustrated not to hear more about the museum. I could not even go and make my own opinion of it since the museum is not open to the public. Schools are welcome, otherwise you have to be a military officials, counternarcotic cadet or visiting diplomat to be allowed entrance.

I’ve gathered below a few facts, links and images about the Museo de Enervantes.

Open in 1985 and located on the seventh floor of the Mexican Defense Ministry building, the private museum documents the country’s drug culture and the government’s battle against the drug cartels. It appear that the main raison d’être of the museum is to teach military personnel about the tricks and strategies deployed by drug barons to hide, smuggle and sell their merchandise.

Many of the pieces on show demonstrate traffickers’ almost unlimited inventiveness:

Drugs hidden in a framed print of the Virgin of Guadalupe

Drugs hidden in a framed print of the Virgin of Guadalupe

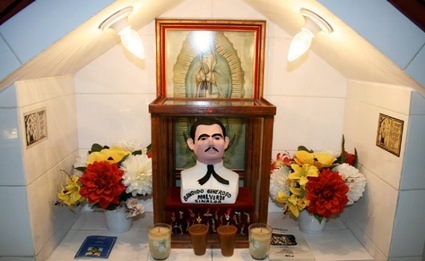

A section of the museum highlights the connection between religions and drug trafficking. A bust of Jesus Malverde is enshrined in one exhibit. According to the legend, the bandit was killed by authorities in 1909. He is revered in the country as a patron saint of traffickers and a Robin Hood for the poor.

Model of a shrine to ‘narco-saint’ Jesus Malverde

Model of a shrine to ‘narco-saint’ Jesus Malverde

The “narco-culture” room is packed with over-the-top bejeweled cellphones, gold and silver-plated pistols (one of them is even engraved with “Better to die on your feet than live on your knees”), jackets with hideaway armor plating, etc.

Confiscated gold- and silver-plated gun

Confiscated gold- and silver-plated gun

After Capitán Remigio Cruz’s presentation several people in the audience questioned President Felipe Calderón’s brutal strategy to fight drug mafias. I didn’t know the exact facts they were referring to until i read Daniel Hernandez’s report which pointed to children caught in the line of fire and human rights violations.

More images: terra, almamagazine, Washington post, newsweek. Reuters has a video report.

And now for something completely different…

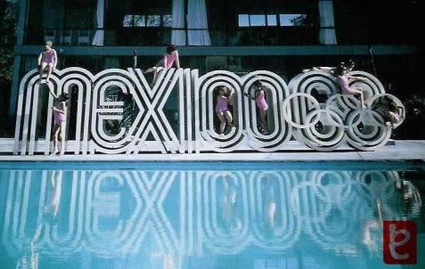

Cassim Shepard from Urban Omnibus had invited architect and designer Eduardo Terrazas to tell us about his awe-inspiring career. The name Terrazas might not sound familiar to many readers but i’m sure that anyone can remember or recognize the identity program he designed for the Olympics Games in Mexico in 1968. He was very young at the time but nevertheless came up with a unique and quite revolutionary design that involved every single element that would represent Mexico to the whole world during the Olympics: from a logotype for the Games to the urban-scale communication and wayfinding system. The design was very modern but it also recalled patterns used by the Huichol Indians.

Eduardo Terrazas, Pedro Ramirez Vasquez and Lance Wyman, Mexico ’68 Identity (via open studio)

Eduardo Terrazas, Pedro Ramirez Vasquez and Lance Wyman, Mexico ’68 Identity (via open studio)

Photo Eduardo Terrazas

Photo Eduardo Terrazas

The architect and designer reminded us that Mexico ’68 is not just a synonym of the Olympics but also of the Tlatelolco massacre, a government massacre of student and civilian protesters and bystanders which took place ten days before the opening ceremonies of the Olympics.

Gabriella Gómez-Mont had invited Antonio Vega Macotela to tell us about the hundreds of hours he has spent inside the Santa Martha Acatitla prison striking deals with inmates.

Cooking grill made by an inmate

Cooking grill made by an inmate

The artist is interested in the concept of time and the way it has been appropriated by institutions and rules outside of us. Work-time is converted into salary, and leisure-time into consumption. Bills and coins have come to represent time better than hands on a clock. For Marcotela the prison is the perfect embodiment of this idea of hijacked time.

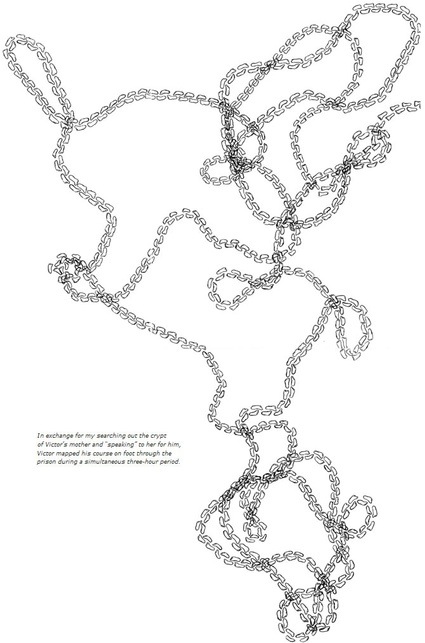

In his project Time Divisa [Time Currency] , the artist explored the possibility of substituting money for mutual favors.The deal he offered prisoners was the following: I would use a certain amount of my time to do things in their representation at a specific day and hour. At the same time they would do whatever I asked them to do as an artist.

Macotela made a total of 365 exchanges with inmates. One asked him to stay with his wife and witness the first steps of his child; another told him to go to his brother’s party and get drunk for him; he also to say a few words on the tomb of a brother; ask a father for forgiveness, etc. He registered everything on video for the inmates.

In exchange, Macotela asked them to measure time using their body. The artist gave many examples. One had to hold his hand to his neck for 3 hours and register each heartbeat on a paper for the artists. Another had to map every step he made in the prison voer a period of 3 hours. Sometimes the artist would ask them to teach his their particular “skills” in exchange for his time (how to kill someone with a shoelace for example.)

More photos and details about the project in both toxico and viceland.

Since this was my last story about Postopolis, i’d like to thank the organizers and sponsors for enabling us to participate in this wonderful experience: Storefront for Art and Architecture, Museo Experimental El Eco, Tomo and Domus Magazine of course but also our sponsors Mexicana, the British Embassy, Urbi VidaResidencial, UNAM, Difusión Cultural UNAM, el Museo Experimental El Eco, Cityexpress and XXLager. And a huge muchas gracias to Daniel Perlin for his bananAs energy, patience and enthusiasm.