If you’re in London and stop by the exhibition High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture at the Wellcome Collection, do take a few minutes to have a look at their window on Euston Road. Curated by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, the window features several design works that attempt to inspire debate about the human consequences of different technological futures by asking ‘What If…?’

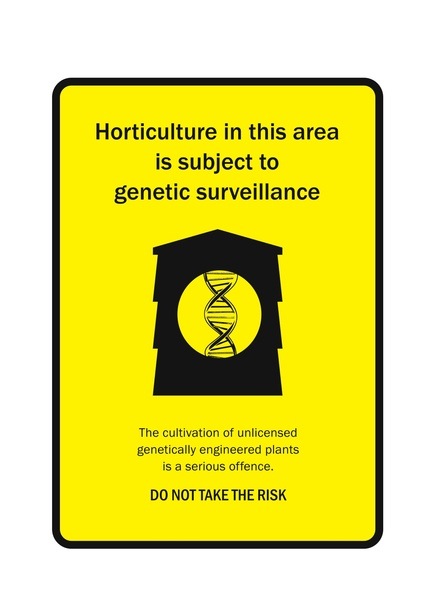

One of the projects currently on show is Thomas Thwaites‘ Policing Genes. The designer collaborated with Prof Gloria Laycock and James French, University College London, to explore a near future society where people -whether they have lawful intentions or not- would be able to genetically engineer plants at home:

Pharmaceutical companies are experimenting with pharming – genetically engineering plants to produce useful, and valuable drugs. Currently undergoing field trials are tomato plants that produce a vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease, and potatoes that immunize against Hepatitis B. Many more Plant-Made-Pharmaceuticals are being developed in laboratories around the world.

However, the techniques to insert genes into plants are within reach of the amateur, and the criminal. Policing Genes speculates that genetic engineering will also find a use outside the law, with innocent-looking garden plants modified to produce narcotics and unlicensed pharmaceuticals.

The genetics of the plants in your garden or allotment could become a police matter…

Have a look at the video to understand how the police apiculture department would work:

How could i not ask a few questions to Thomas about Policing Genes?

Your project was inspired by research on pollen forensics at the Centre for Security and Crime Science at University College London. I just read this field is called ‘palynology‘ and is already used by the police or for searching war criminals. Who at the University College have you been in contact with? What exactly are they researching right now?

I spent some time interviewing a PhD student James French. He’s working on the transfer, and secondary transfer of pollen from one person to another. Even habitats that seem quite similar (two patches of woodland say) can actually have quite distinct ‘pollen assemblages’ – like a signature, made up of the types and amounts of pollen from plants in an area.

At the moment, by examining a sample of pollen from somebody’s clothes, you could be confident of whether or not, for example, ‘they’ve been in the same woods where the body was found’. This obviously is quite useful if your suspect claims he’s been at home in London answering his emails, but the pollen on his clothes isn’t from London gardens, but from a oak woodland. Equally, a lack of pollen can rule people out of the investigation.

However, what if the criminal washes their clothes, or moves the body from one location to another. Work that James and others are doing aims to characterise how much pollen you’d expect to find in the washing machine, or on the car seat or sofa after they’ve been sitting on it. If the body was moved from a garden in London to some woodland, they want to know how much pollen from the garden you’d expect to find after X days… meaning you could say that the body was moved X days ago.

Are the police in the UK already using pollen forensics?

Are the police in the UK already using pollen forensics?

Yes, and its been pretty instrumental in several very high profile cases. There’s this lady called Pat Wiltshire who is the police’s go-to person for pollen forensics. She can look at a sample of pollen from clothes or whatever, and visualise the landscape it’s from – a filed of maze, with a river next to it, and an oak tree in the middle – or something like that. The impression I got about police work when I was interviewing James, and a detective, was that it’s really arduous. Pollen forensics would be one detail in many that would lead to cracking a case, and as importantly, proving it in court.

![]() How did the pollen forensics researchers react to your project?

How did the pollen forensics researchers react to your project?

In general the reaction was that it was almost believable… which is the reaction you want for a futures project I think. A plant geneticist, (who’s ‘Crash Course in Synthetic Biology’ I later crashed) saw the project and said he’d thought about taking genes from the Marijuana plant and putting them into a tomato plant (being a respected scientist I’m sure he wasn’t saying he’d thought about ‘doing it’, just ‘about it’).

The abstract of the work says that “the techniques employed to insert genes into plants are within reach of the amateur…and the criminal.” Is it already the case today? How much genetic manipulation would i be able to do nowadays using only off the shelf instruments and basic information i could find online?

The abstract of the work says that “the techniques employed to insert genes into plants are within reach of the amateur…and the criminal.” Is it already the case today? How much genetic manipulation would i be able to do nowadays using only off the shelf instruments and basic information i could find online?

A couple of months ago I was invited to participate in a ‘Crash Course in Synthetic Biology’ at Cambridge University. This was a two week thing, about half in the classroom and half in a wet lab. In the lab, over the course of three days, working in small groups, we inserted a gene into an e-coli bacterium that made it glow green under UV light. This is the standard beginners thing in genetics – the ‘hello world’ of the genetics lab, and not particularly interesting in itself – anymore.

What is interesting is what our lab supervisors said about it. When they’d been doing their PhDs five years ago, what we’d just done in three days would’ve been considered an excellent four year PhD. And just the first part of the process – that took us half a day – would’ve been a PhD ten years ago. Four years to three days over the course of five years – this is a rapidly developing field!

We were basically following a recipe – using off the shelf techniques and ‘tools’ – enzymes which cut and join DNA that come with instructions for use. These can be bought from any biotech supply company (I don’t think you even need some kind of license to order them). Genetics is becoming abstracted and standardised – its turning from a science to an engineering subject.

What could you or I do tomorrow…? I don’t want to get all overblown and techno-hype, but the field is developing quickly. I literally just had a look online, and have downloaded a paper describing the DNA sequence for the genes which make THC in the Marijuana plant (the ‘active ingredient’), and how to insert this gene into the tobacco plant. It looks a complicated process to follow, but with some close reading, and if I could buy the right enzymes and vectors (the ‘standardised tools’ I mentioned), I reckon I could have a good go at inserting the gene encoding THC into the Tomato plant – making ‘tomarijuana’ or ‘marijmato’. And I am without doubt an amateur as far as biotech is concerned.

You are showing genetically engineered samples in the Wellcome window. Was any of them inspired by existing manipulated plants?

You are showing genetically engineered samples in the Wellcome window. Was any of them inspired by existing manipulated plants?

The plant samples in the window are real plants (though non-gm in actual fact). Genetically modified plants don’t glow in the dark or whatever – unless that’s what they’ve been modified to do – they look exactly like their non-GM counterparts.

But yes, the futures scenarios I use them to describe were inspired by existing manipulated plants.

The GM Tomato plant was directly inspired by research from Korea, where they’ve grown tomatoes modified to contain an edible vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease. In the scenario described, I was speculating on whether little old ladies might grow their own unlicensed anti-ageing drugs on their allotments!

If the Korean early stage research does eventually prove successful, then whichever pharmaceutical company that develops the vaccine will of course want a return on their investment. Alzheimer’s and other diseases associated with ageing, obviously fall most on societies which are rich enough to age – hence the interest by pharmaceutical companies in developing medicines for them. But with our rapidly ageing population, it’s likely that anti-ageing drugs will not be made affordable for all – there’s lots of debate in the UK about whether the NHS can afford to pay for increasingly expensive drug treatments as more and more people live long enough to need them. But if you could grow your own, even from ‘pirated’ seeds, then I think most people certainly would if they needed the drugs.

The broad beans ‘modified by amateurs’ to produce benzoylmethylecgonine (cocaine), and the sunflower that has been modified to produce a poison are feasible. These scenarios though are illustrations of the ‘dual use problem’ that rears its head with every new technology – the problem that technology developed for good can also be turned to ‘evil’.

The War on Drugs (ridiculous name) – is a program run by the USA to stop the supply of cocaine and so on, at its source. This involves flying crop-dusting planes over plantations of coca plants in Columbia, and spraying the coca with glyphosphate. Glyphosphate is a powerful herbicide and will kill most plants. It’s also what Monsanto engineered their ‘Roundup Ready’ variety of GM soya plants to be resistant to. So farmers can spray their fields of RoundUp Ready soya crops with glyphosphate, and kill all the weeds in the field but leave their GM soya plants to thrive.

The thing is, a few years ago, plantations of coca in Columbia stopped dying off when sprayed with glyphosphate. This led to speculation that the drug barons had used the same technology that Monsanto had used, to genetically engineer glyphosphate resistance into their coca plants. So, a chap went down to test for GM markers in the coca – as it turns out he didn’t find any, so the conclusion was that glyphosphate resistance had arisen through selective breeding. But the fact that the question of whether the coca had been genetically modified or not even arose, gives credence to the idea that a drug baron with plenty of $ could quite easily set up a genetics lab, and employ some poverty stricken PhD students to create GM coca, or whatever.

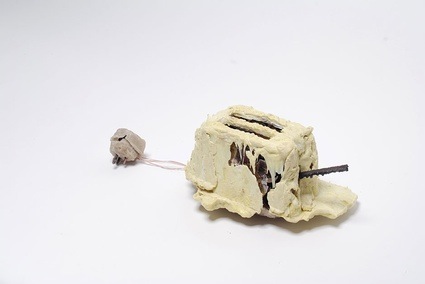

Are you still working on that famous toaster?

Are you still working on that famous toaster?

I wrote up the project in a kind of book (graphic designed by my friend A Young Kim) which I exhibited alongside the toaster. In a moment of ‘slightly drunken networking’ (the only ‘networking’ I do), I showed it to Michael Bierut who’s a partner at Pentagram design in New York, who liked it and who showed it to his friend who’s a publisher at Princeton University Press, who also liked it, who’s going to publish it (!) – once I’ve done some edits – and not until Autumn 2011 (there’s a weird thing in the book world apparently where one only publishes one’s book in either the Spring or Autumn).

As for the toaster itself, I haven’t been able to improve it for some time now as I keep on saying ‘sure’ to any exhibition opportunity that presents itself, (which keeps it out of the flat – always good). It’s going to be shown at the Science Museum in London for a year from next April, next to Stephensons’ Rocket, which is frankly insane – my (extremely) badly made toaster, next to the first steam locomotive ever built – but it’s something I’m of course insanely pleased about.

Thanks Thomas!

All images courtesy of the designer.