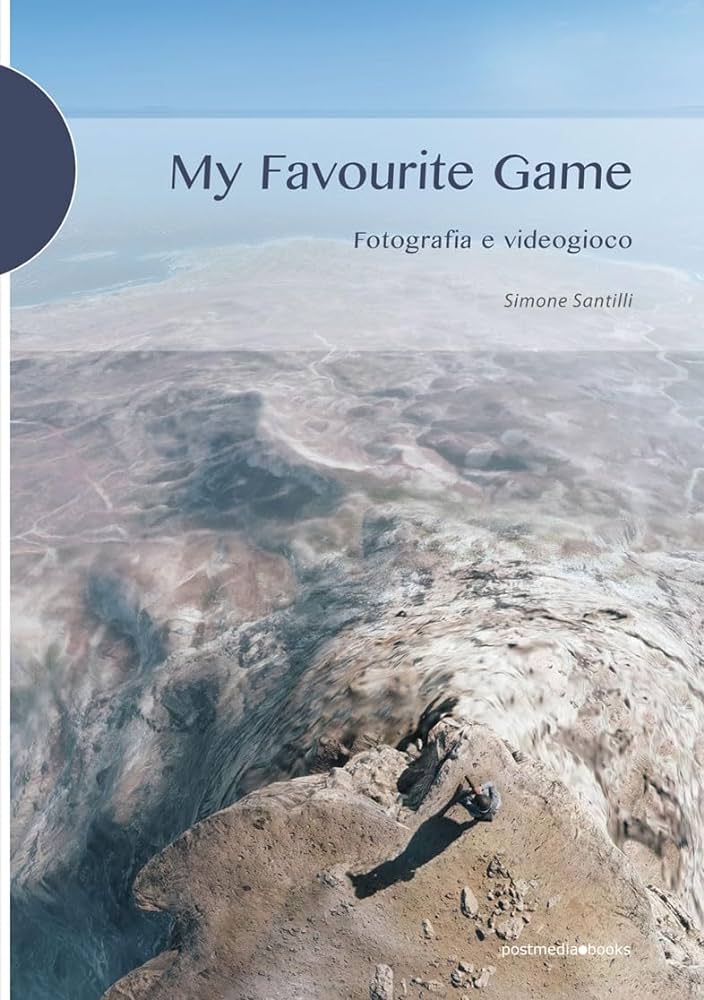

My favourite game. Fotografia e videogioco, by artist and teacher Simone Santilli. Published by Postmedia Books.

The books i enjoy the most cover topics i know very little about in an entertaining, yet erudite way. Or vice versa. My favourite game. Fotografia e videogioco not only explores a field i’m fairly ignorant of -the osmosis between photography and gaming- but it is in Italian. Which makes it doubly interesting because I always welcome viewpoints that do not solely focus on US/UK research.

Leonardo Magrelli, West of Here, 2021

Robie Cooper, Alter Ego, Jason – Rurouni, 2007

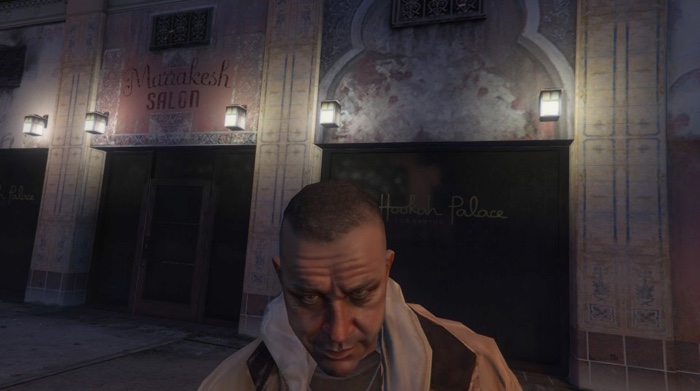

Alan Butler, Down and Out in Los Santos, 2015-ongoing

Western society binges on visual culture. Not only do we take more photos than our eyes and brain can process, we’re also consuming images that are shot in the virtual world by us and by bots. With intention or automation. Computer-generated images are quietly colonising our reality. Even today’s photo devices use software that erases movement, red eyes and other flaws, engineering selfies that look like avatars and capturing scenes of street life that might be confused with the ones in GTA.

Nowhere is this blurring between the real and the virtual more evident than in video games. My favourite game investigates how the conversation between photo and video games is shaping our perception of reality and how it has given rise to a series of fascinating artistic experiments and theoretical research.

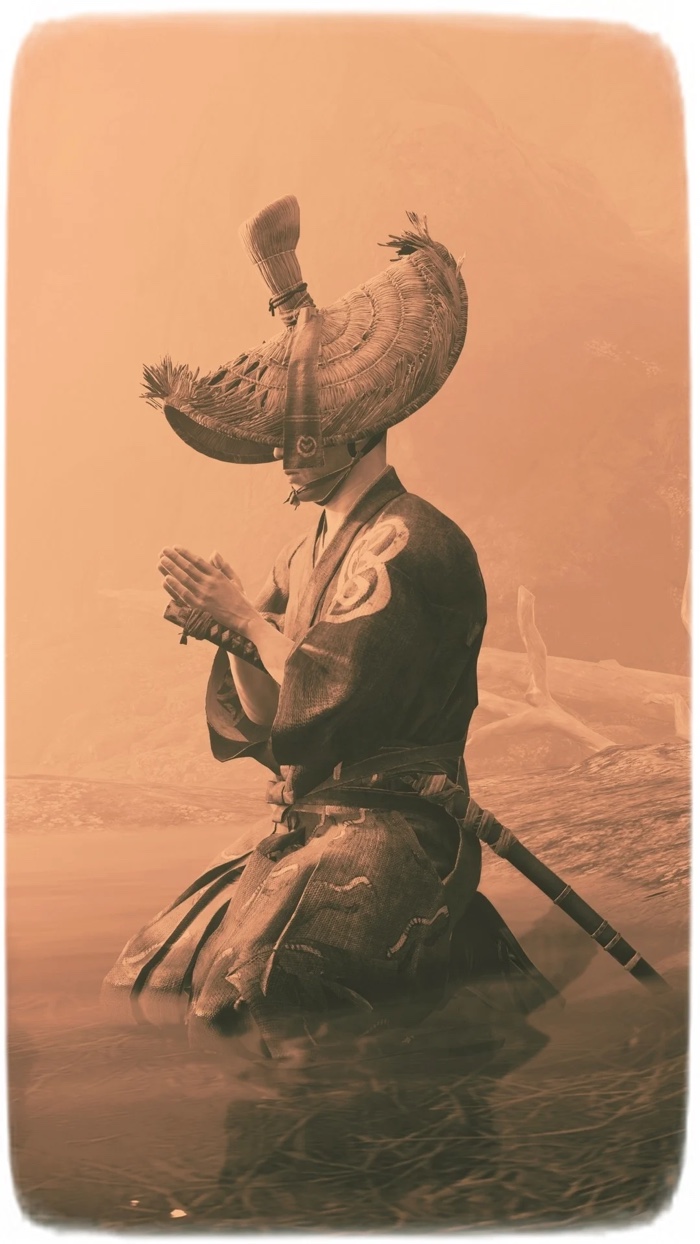

If, when we think of the relationship between photography and videogames, the first thing that comes to mind is in-game photography, the set of photographic practices carried out within and through computer games, the relationship between the two media is much more articulated. Photography and video games are products of the industrial, military and ideological apparatus of the West and embody its cultural biases. Both are characterised by the presence of a code, which conditions the user’s freedom, and by the link with exploitation processes typical of late capitalism that monetise the investment of time and energy of players/photographers.

As Simone Santilli demonstrates, the seeds of the intense exchange between play and images can be found in the history of photography: photographers have always subverted the rules of their medium of choice, playing with subjects, blurring genres, defying viewers’ expectations, constructing and distorting reality.

Pascal Greco, Place(s), 2021

Kent Sheely, Grand Theft Photo, 2007

The book describes the practices, processes, devices, world building tactics, actors, models and modalities that characterise in-game photography. In video games, photography is more predictable than in real life and while computer-generated images are becoming uncannily photorealistic, non-realistic video games can still offer experiences perceived as real.

Many in-game photographers, however, explore the same genres as “traditional” photographers. They face the same social, political, cultural, economic and environmental conditions. They often have the same motivations too. They photograph to document, entertain, enchant, reveal hidden ideologies, protest, experiment, manifest their existence and invite critical reflection. Their images often enter the real world and remodel ideas and discourses about photography and about the nature of reality itself.

Emanuele Bresciani, The Many Faces of Tsushima Island, 2021

If you read Italian and have an interest in gaming, photography or visual culture in general, do get a copy of the book. And if you’re anywhere near Milan next week, don’t miss the First Italian Conference on In-Game Photography/Primo convegno italiano sulla fotoludica at IULM University, organised by Matteo Bittanti in the framework of the seventh edition of the Milan Machinima Festival.

Danielle Udogaranya, Custom Avatars for the Sims, 2015

Total Refusal, Operation Jane Walk, 2018