I’m just back from the IxDA Interaction 08 conference organized by the Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia. My favourite talk was Strategic Boredom by Molly or how two visionaries from the ’50s and ’60s could teach us something about introducing boredom into interaction.

Molly Wright Steenson is a PHD student in architecture at Princeton University and an interaction designer.

Molly Wright Steenson is a PHD student in architecture at Princeton University and an interaction designer.

When i realized that Molly posted most of her talk on her new blog Conceptual Device, i thought i could just add it to my del.icio.us links but then it would be lost for most of my readers. So i’m going to let you read the intro on her site and take over with what i wrote down during her talk, from the moment when she focused on Gordon Pask and Cedric Price. Not sure it makes much sense but it does make me happy. This blog was born out of a need to archive what could serve my own enlightenment after all.

Martin Heidegger studied boredom in Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics as part of his continual exploration of existence. At some point he suggested an interesting strategy when facing boredom: “not to resist straightaway but to let resonate… only by not being opposed to it, but letting it approach us and tell us what it wants, what is going on with it.”

The idea of exploring boredom took an interesting turn with cybernetics,

Louis Kauffman, President of the American Society for Cybernetics, defines cybernetics as “the study of systems and processes that interact with themselves and produce themselves from themselves”.

There is first order cybernetics (not much interaction here) and second order cybernetics (an organism or social system is an agent in its own right, interacting with another agent, the observer.)

Gordon Pask was interested in Second Order Cybernetic. Pask had a PHD in psychology and was particularly interested in learning and conversations.

Gordon Pask (Photo by Harry Kerr/BIPs/Getty Images)

Gordon Pask (Photo by Harry Kerr/BIPs/Getty Images)

In 1953, Pask created the Musicolour machine. The machine was inspired by the concept of synesthesia and aimed at exploring what happens when music and light interact with each other. He’s the only one nor the first to work on such idea but what makes the Musicolour interesting is that Pask introduced the notion of boredom in the equation.

The work held a “conversation” with the performer. The musician would respond to visual queues, the machine in turn would build an understanding of what the musician was playing, and, when it detects that the musician is repeating a same sequence too often, the system would “get bored” and challenge the musician to find new ways to re-engage the system.

The idea of building upon boredom reappears with Cedric Price‘s Generator. Just like Archigram, Price didn’t build much but his radical ideas had a huge influence on contemporary architecture. At the core of Price’s practice was the belief that new technology could enable the public to gain control over their environment, resulting in a building which could be responsive to visitors’ needs and the many activities intended to take place there.

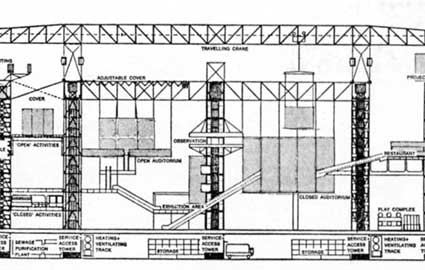

The Fun Palace, probably his most influential projects, was never realized but it nevertheless inspired the Centre Georges Pompidou that Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano built ten years later in Paris.

Fun Palace, an unrealised project for East London, 1960-1961

Fun Palace, an unrealised project for East London, 1960-1961

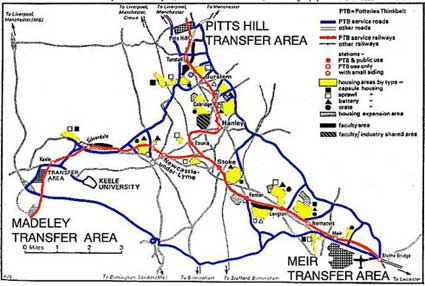

Price became also famous for his project of a mobile university on rails, the Potteries Thinkbelt (1965). He proposed the conversion of declining industrial zone into a huge High Tech think-tank, with mobile classrooms and laboratories mounted on the rail lines, moving from place to place, from housing to library to factory to computer center.

Plan for Potteries Thinkbelt, Staffordshire, England, 1965

Plan for Potteries Thinkbelt, Staffordshire, England, 1965

Price was not interested in formalism but in conditions that would change people behaviour through their interaction with architecture.

The idea reappears in Price’s Generator (1976-79, not built). This series of cubes, screens, walkways and catwalks could be moved around by a mobile crane on the site to meet visitors’ needs and desires. Price’s collaborator John Frazer, proposed that the cubes be outfitted with sensors that would report on the use of the components. If the pieces of Generator weren’t moved enough, they would grow bored and design their own layouts, which in turn would be handed off to the mobile crane operator to put into place.

In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Price declared:

In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Price declared:

In defining architecture, you don’t necessarily define the consumption of it. All the designs we did for Generator [Florida, 1966] were written as menus, and then we would draw the menu, and because I like bacon and eggs for breakfast, it was all related to that bit of bacon and that bit of egg. They were all drawn, however cartoon-like, in the same order – not in the order the chef or cook would arrange them on your plate, but in the order in which the consumer would eat them. And that is related to the consumption or usefulness of architecture, not to the dispenser of it.

Generator would also have the task to surprise its users. In collaboration with programmer-architects John and Julia Frazer, he imagined that each element of Generator would become “intelligent” by being outfitted with a microchip. The sensors would interact with four computer programs that performed a variety of tasks, including keeping inventory, aiding Generator’s users to design different layouts, and most powerfully and importantly, getting bored. The boredom routine would run if people did not request changes of Generator frequently enough, or if the parts were not aptly used. It would draw up new plans for Generator, which would be handed off to the social elements of the project.

John and Julia Frazer, Generator Electronic Model

John and Julia Frazer, Generator Electronic Model

In the correspondence between Price and his system research consultants Julia & John Frazer, Molly encountered this thought-provoking sentence: “If you kick a system the very least you would expect is for them to kick you back.”

What interested Price was not to design the perfectly controlled system but to create a Generator which would make things that neither the architect nor the users expect, a system that gets involved and plays an active role once it gets bored. That was his idea of interaction: a troublesome system that bites back, that engages in a conversation and do things you wouldn’t have thought about, no matter how carefully you have devised that system.

Previously: Paskian Environments.