Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Olive Tree), 2012

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Olive Tree), 2012

Tomorrow FACT in Liverpool is opening Science Fiction: New Death, an exhibition which explores how advances in technology are making everyday lives feel increasingly similar to universes so far heralded by science-fiction.

One of the works in the show is a spectacularly seducing short film by Larissa Sansour. Nation Estate proposes a vertical solution to Palestinian statehood. Instead of navigating their currently heavily fragmented and controlled territory through dispiriting screening processes and check points, Palestinians living in an undetermined future would be housed inside a colossal high-tech skyscraper. Each city (Jerusalem, Nablus, Ramallah, etc.) would have its own floor. The building is surrounded by concrete walls but its inhabitants would be able to travel in and out of their country using a highly efficient subway system and go from one Palestinian city to another using an elevator.

Nation Estate (clip)

As i wrote above, the images in the film are very seducing. Their sleek aesthetics is full of irony and humour but the dystopian scenario also alludes to the absurdity and complexity of every day life for Palestinians.

Conceived in the wake of the Palestinian bid for statehood at the United Nations in 2011, the work comments on the shrinking territory of the Palestinian state and the difficulty for its inhabitant to move from one city to another. In 2011, the work was nominated for a prized sponsored by Lacoste at the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne. The nomination was then revoked as the sponsor found that the work was “too pro-Palestinian.” Furthermore, Sansour was asked her to sign an agreement saying that she had chosen to withdraw herself from the competition.

The censorship attracted the attention of the press and the museum eventually took the decision to side with the artist, breaking off their relationship with Lacoste.

What makes Nation Estate so powerful is that you can very well imagine that the whole Palestinian population might one day be confined to a sole high-rise building. And what makes Nation Estate even more powerful is that you can just well imagine that they won’t even be allowed to do that. At least, not on what is left of their own land.

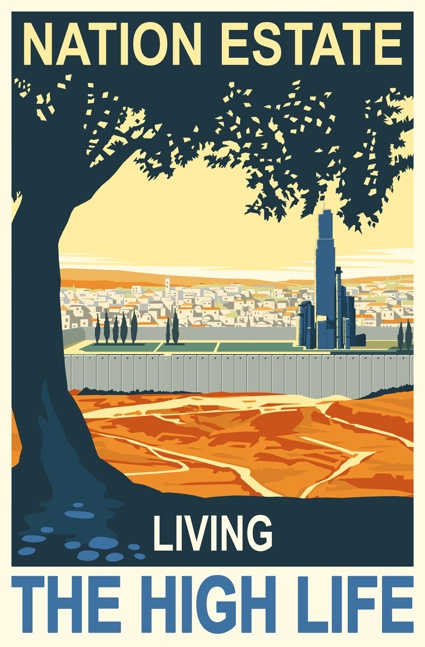

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Poster), 2012

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Poster), 2012

Born in Jerusalem, Larissa Sansour studied Fine Art in Copenhagen, London, New York. Her work is interdisciplinary, immersed in the current political dialogue and utilises video, photography, installation, the book form and the internet. I’m thrilled that she accepted to answer my questions about her work:

Hi Larissa! Why did you decide to give Nation Estate a sci-fi, futuristic treatment? What does sci-fi and a dystopic approach bring to your work that a setting in a realistic present wouldn’t allow?

I feel that Palestinians are currently living through a stretch of post apocalyptic history. Politics on the ground is so surreal, that it is sometimes hard to comment on what is going on there in just a straight forward way. Sci-fi often predicts humanity’s future and future concerns. The world that sci-fi films and literature usually build, reflects our unease with progress and technology and its clash with organic matter in the world. In the same way, I think Palestine has been undergoing a very harsh and fast shift in their reality under the rational modernist Construct of the Israeli State and all of the calamities that that entailed for Palestinians. As the international community is still struggling to reinforce the law on the expanding Israeli settlements and other violations of human rights by the state of Israel, the Palestinian people have been pushed to living under subhuman and often very surreal conditions. It only feels appropriate to reflect that reality in a visual language that matches that other worldliness lived by Palestinians.

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Main Lobby)

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Main Lobby)

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Jerusalem Floor)

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Jerusalem Floor)

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Manger Square)

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Manger Square)

I saw an extract of Nation Estate a few weeks ago during a talk you gave at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. I was particularly interested in the transport system the film portrayed. Could you explain how the subway and elevators work? And why you have people move underground or vertically?

Nation Estate posits and imagines a Palestinian state in the future. As it becoming harder and harder to understand what a viable Palestinian state would look like, seeing that Israeli settlements are slowly eating away at what is left of Palestinian territory, the film suggests that the only way we can imagine a feasible Palestine is in vertical form rather than horizontal, due to there being no more land left for Palestinians. Nation Estate is a highly futuristic technically advanced skyscraper that houses the entire Palestinian population. Each floor represents a different Palestinian town, Ramallah on the 3rd floor, Jenin on the 5th, Jerusalem on the 7th, Bethlehem on the 21st and so on. So, trips between towns that at present are very hard to make due to Israeli checkpoints would become so easy, as they are made by way of an elevator. The building also features a great development for Palestinians and that is the ease of movement between Jordan and Nation Estate.

Palestinians are currently not allowed to use the Israeli airport, which would make trips from and to the outside world easier. Instead all Palestinians have to enter Palestine through Jordan which makes it a much longer journey. In Nation Estate, a new line between Amman and Palestine is constructed, the Amman express underground, which only takes 15 min.

During that same presentation you also mentioned the fact that, as a Palestinian artist, you had to deal a lot with attention fatigue. Could you expand on this?

During that same presentation you also mentioned the fact that, as a Palestinian artist, you had to deal a lot with attention fatigue. Could you expand on this?

I think the world has grown weary to news footage that is coming out of the Middle East and especially to news coming out of Israel and Palestine. The problem at hand is more than 60 years old and it is most often than not represented as a conflict, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So, people get the impression that it is a conflict between two equal powers that just can’t get along and the reasons are most often ascribed to religion, whereas in reality what is happening in Palestine is another form of colonialism. Not coming to terms with that unfortunately only feeds the desperation for any solution to be found and continues the cycle of blaming the two sides, while the stronger side keeps getting stronger and the tragedy just keeps getting worse. And I think audiences from outside of Palestine have grown immune to any information coming out of that region as all the news seems repetitive and the situation at hand seems to be futile and beyond help.

I would also expect that, once again as a Palestinian artist, you meet with politically-motivated pressure. The Lacoste sponsorship is the obvious example but could you give more examples of this sort of censorship?

What was disturbing about the Lacoste sponsorship is how blatant the censorship was. I was basically told, we decided to remove your name from the 8 nominees list. Also, what made it even more sinister is that I was asked the next day, to sign a paper saying that I left the competition according to my own personal decision to seek other opportunities. It is was very clear that Lacoste did not think that an artist has any power to battle such a giant fashion company like themselves. Fortunately, things did not go according to their plan.

But I did experience other forms of censorship. I guess one cannot call them censorship as such as it is more subtle than that. But many Palestinian artists are just simply not selected, or subjected to systematic silencing. Several times, I was asked to change the titles of my shows because they sounded too problematic, politically speaking. Several years ago, a group show I was in in the US, nearly closed down before opening night, simply because it featured too many Palestinian artists. The show was finally allowed to open on the condition that the catalogues that accompanied the show were not made public. So, these various forms of silencing unfortunately happen often.

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Food), 2012

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate (Food), 2012

How do Palestinian people react to this vision of the future nation that your film gives?

I am happy that Palestinians usually respond really well to my work. I think Palestinians can identify quickly with the surreal and dystopic elements in my films since we all had to deal with the surreal and absurd realities that the Israeli occupation has imposed on us.

A Space Exodus

I also saw Palestinauts at Cornerhouse in Manchester two years ago. It was part of an exhibition called Subversion in the Arab Art world. Both Nation Estate and Palestinauts are set in the future and what strikes me is that neither of the work contain any direct reference to Isreal. Why is Israel absent from the films?

Even though Israel is never mentioned directly, it is completely present in its absence. These apocalyptic conditions that are imposed on the Palestinian people, whether in the form of outer space or architectural displacement, are all a direct result of the Israeli occupation. And since that is very obvious, I would only be resorting to direct documentary style form if I am to reiterate that. I think having Israel absent reinforces the fact that the films are projected. They function as parallel universes, rather than solutions. They address our concerns as a humanity in general, a universal angst for the future.

Larissa Sansour, Palestinauts. Installation shot at Cornerhouse. Photo credit WeAreTAPE.com

Larissa Sansour, Palestinauts. Installation shot at Cornerhouse. Photo credit WeAreTAPE.com

What do you think can be the impact of art on political issues? Which place does it have in a political dialogue? Whether we are talking about Palestine or other political issues.

It is always difficult for an artist, I think, to find a balance between the two, politics and art. I often find it uncomfortable to be put in the position of a political spokesperson devoid from the artistic context. The mere fact that my artistic work is immersed in politics should not mean that I have to resort to the same political discourse outside of art. There is a potency to art that should be preserved as unique and its impact on the political dialogue cannot be underestimated. That is why it is a difficult act for me to juggle all these positions.

Nation Estate, for example, does not propose any course of action, nor does it in any simple terms suggest any kind of right or just solution to the problems at hand. It merely responds to a completely unacceptable state of affairs and attempts to take one possible surreal, absurd and radical set of consequences of accepting the status quo.

What is next for you? What are you working on?

The project that I am working on now, is a performative counter-measure to the unearthing of artifacts in order to justify further confiscation of Palestinian lands and erasure of Palestinian heritage. In the absence of any real peace process, archeology has become the latest battleground for settling land disputes. Unearthed history is used as arguments for rightful ownership of the land today. In this project, 2-300 pieces of elaborate porcelain – suggested to belong to a future nation of hi-tech, highly sophisticated, yet entirely fictional Palestinians – are buried deep into the ground in the West Bank, for future archeologists to excavate. Once unearthed possibly hundreds of years from now, this tableware will provide physical evidence supporting the myth of the historical hi-tech people, thus justifying future Palestinian claims to their land.

The project stretches the very idea of fiction beyond its natural boundaries by not just fabricating a myth of a future hi-tech nation, but rather physically constructing evidence for this myth as informed by real events, hence providing the tools for the myth to present itself essentially as a non-fiction. The work itself becomes a historical and narrative intervention – de facto creating a nation.

Thanks Larissa!

Science Fiction: New Death, curated by Omar Kholeif and Mike Stubbs, will be open at FACT in Liverpool from 27 March till 22 June 2014.