In 2012, French philosopher Bernard Stiegler elaborated his idea of an “automated society,” a society deeply transformed by the increasing automation of every single aspect of our lives, from mundane daily activities to thought processes. The delegation of cognitive and physical task to machines and algorithms, he believed, was not a problem per se. What worried him was that the automation depends on ROI; it obeys the laws of the market. It makes possible the total marchandisation of all the dimensions of the living.

Félix Luque Sánchez. Installation view at iMAL in Brussels

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Assembled in China, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, La Société automatique at iMAL in Brussels

La Société automatique, Félix Luque Sánchez‘s ongoing show at iMAL in Brussels, pays homage to Stiegler’s subtle critique of unchecked technological progress. The eight new works in the show (created in collaboration with Vincent Evrard, Damien Gernay and Íñigo Bilbao Lopategui) present a vision of a society where automation invades every aspect of our lives and gradually supplants human agency.

Luque Sánchez is renowned for his science fiction aesthetic and narratives. The works in the exhibition maintain his signature sleek, ethereal and ambiguous atmosphere. And that feeling that the tech industry is based on myths as much as on science. This time, however, the speculative element has taken a back seat and the show raises profound questions not just about technology but also about ourselves. Have we really taken stock of what technological “progress” is doing to society? Is it too late to reaffirm human values and agency in an increasingly automated world?

The scenography plays an important role in La Société Automatique. A series of white rooms leads visitors from factories to a teenager’s bedroom, from performance space to crash test facilities. iMAL becomes a sequence of spaces where seduction balances anxiety and where the artists build a narration about the growing place that automation is taking in our life.

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Assembled in China, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Assembled in China, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Assembled in China, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Assembled in China, 2025

One of the first works in the show is a striking video triptych and a series of posters that portray Chinese workers. Their eyes seem to betray the working conditions hidden behind the products mass-produced for Western consumers. Captured in close-up during moments of silent waiting, their faces express exhaustion and alienation.

You don’t usually get to see these workers. They tend to be anonymised, if not entirely hidden. Assembled in China appears to finally bring these individuals to light. Except that the people portrayed do not exist; their faces were generated by AI. The work exposes the double invisibilisation of the workers. The first one is guided by the logic of globalisation which focuses on the end product, not on its human, environmental or ethical dimensions. The second invisibilisation is the result of the neoliberal fable that machines will inexorably replace humans.

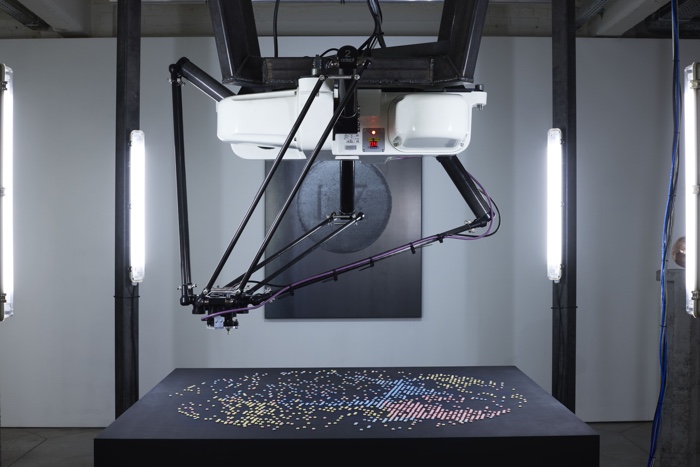

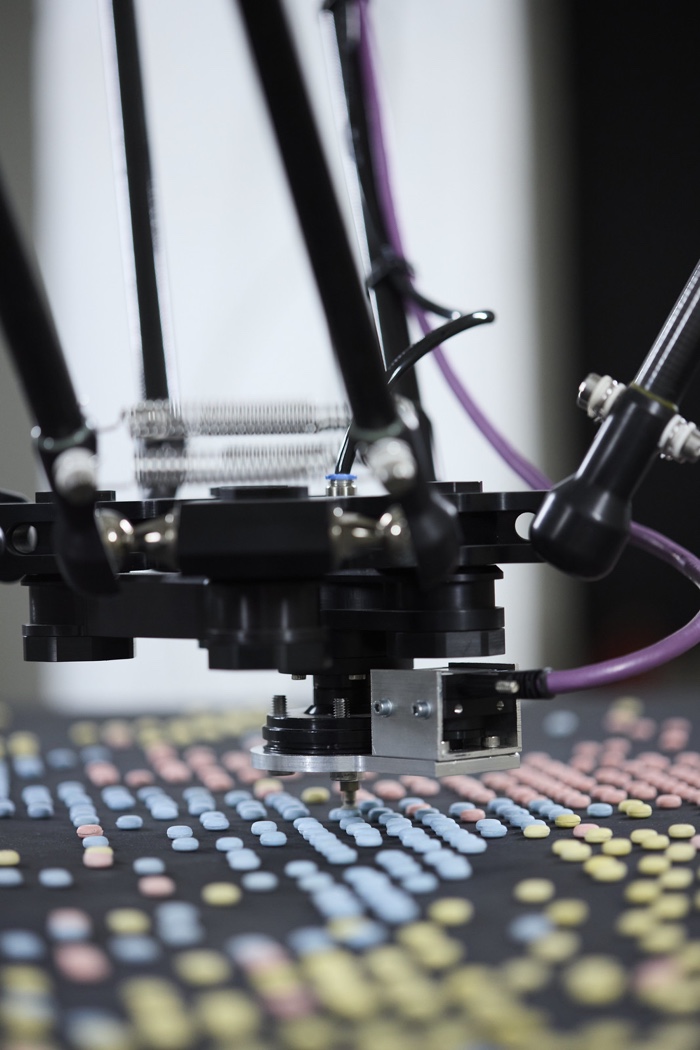

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Damien Gernay, Vincent Evrard, Perpétuité II, 2023–25

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Damien Gernay, Vincent Evrard, Perpétuité II, 2023–25

Félix Luque Sánchez, Iñigo Bilbao Lopategui, Damien Gernay, Vincent Evrard, Perpétuité II, 2023–25

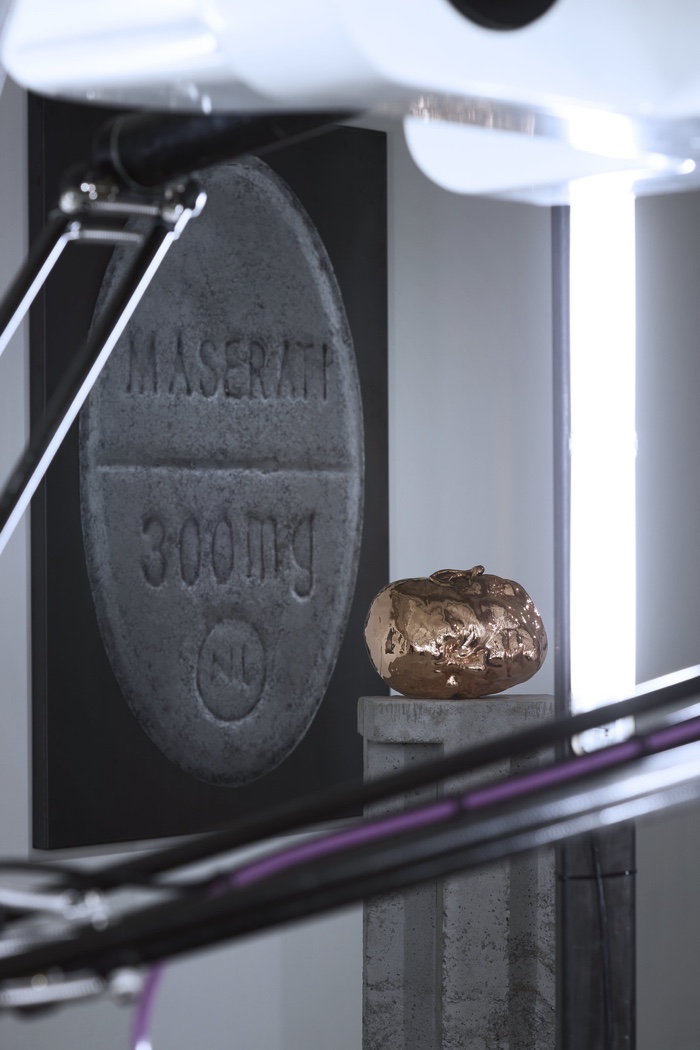

Perpétuité II is a modified industrial robot originally developed for the pharmaceutical industry. The arm of the machine tirelessly maneuvers pastel coloured pills around the table. Driven by an algorithm, its moves simulate the synaptic activity of human neurons. That’s just about the only organic element the robot might have in common with us, though. Unlike human workers, the robot doesn’t get bored or distracted, doesn’t err (in theory at least), doesn’t need a bathroom break, doesn’t care if its task has no end. Bonus! The robot doesn’t even have labour rights!

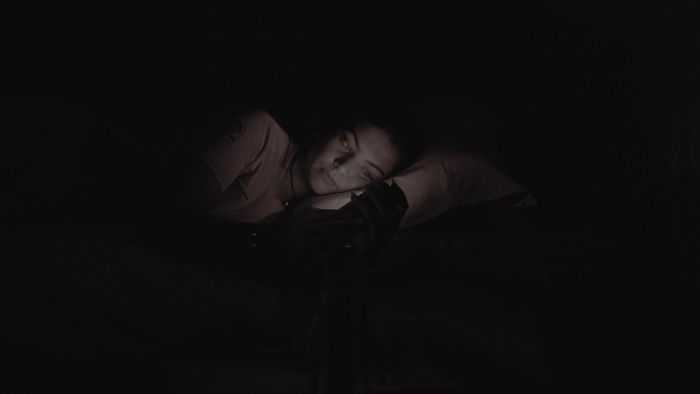

Félix Luque Sánchez, The Sleepers. Exhibition view at iMAL

Félix Luque Sánchez, The Sleepers. Exhibition view at iMAL

The robot is surrounded by sculptures of sleeping (or dead?) people. They are covered in copper, an essential component of electric conductivity and computing. Is this our fate if machines were to take over all our jobs?

On the walls are prints on metal plates of psychotropic pills: tranquilisers, antidepressants, anxiolytics, sleeping pills, psychostimulants… These substances help workers fix their “flaws,” perform more like machines and tolerate any form of alienation engendered by technocapitalism.

The robotic arm, the drugs and the copper head evoke a Silicon Valley neoliberal utopia where machines replace humans. They’ll be autonomous and ever industrious. Despite all our efforts of physical and cognitive “upgrades”, we’ll eventually have to declare forfeit and lie dormant.

But is this really what is in store for humanity? I want to remain optimistic (or naive) and remind myself that we’ve heard that story before. From industrial production to ChatGPT, from Taylorism to autonomous cars, we’ve been told that total automation was around the corner. In 1930, for example, John Maynard Keynes famously predicted that technological progress would enable us to work just 15 hours a week by 2030. The prediction remains a fantasy. Not only has capitalism driven us to want more (goods, leisure, prestige) and work more to obtain it, but AI still relies on a largely obscured and often poorly paid workforce.

Félix Luque Sánchez, Le rêve de Simondon, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Le rêve de Simondon, 2025. Installation view at iMAL

Le rêve de Simondon (Simondon’s Dream) is a series of 8 photos that portrays teenagers carrying out car manufacturing and repairing tasks.

The work is named after the philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon who, in mid-20th-century France, advocated for a culture in which technological education would be considered as essential as literacy to meaningful participation in society. He believed that this pedagogy could help prevent the alienation from the machines. Equipped with this education, we’d be able to recycle, repair, modify and emancipate from technology.

The title is ironical. Simondon would probably be appalled at the level of tech ignorance we are kept in. Instead of technological awareness, we experience black boxes, planned obsolescence and opaque production processes. Yet, this obfuscation of the inner workings of technology is not a fatality; it’s driven by the ideology behind consumerism and extreme capitalism.

The young people in the photos are working on engines that look so complex that I thought the photos were AI-generated. The images are real, they were taken by Luque Sánchez during workshops at a vocational secondary school in Dieppe. Will these teenagers, who have a hands-on experience of technology, fare better than others in the age of the automated society? How can education critically engage with opaque systems? Is it too late for younger generations to reappropiate technology?

Félix Luque Sánchez and Vincent Evrard, in collaboration with Ben Bertrand and Mercedes Dassy, Perpétuité III, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez and Vincent Evrard, in collaboration with Ben Bertrand and Mercedes Dassy, Perpétuité III, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez and Vincent Evrard, in collaboration with Ben Bertrand and Mercedes Dassy, Perpétuité III, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez and Vincent Evrard, in collaboration with Ben Bertrand and Mercedes Dassy, Perpétuité III, 2025

Perpétuité III is an installation in 3 chapters. In the first room, a film shows a dancer and a musician performing in white space. She adopts poses i’d associate with a fashion influencer. The second space is the room where the performance was filmed. The technical apparatus is still there, reproducing exactly the lights, camera motions and environment of the performance. This time, however, we are the performers. We watch the camera moving from one part of the room to another, just like it did during the performance. We experience the same lighting modulations as the ones developed for the performance. Except none of us has the brio and talent of the dancer. The third room shows the performance we gave in room 2. We didn’t realise we were being recorded. There’s a delay of a few minutes between our passage in room 2 and the screening of its recording in room 3. If you stay long enough, you can watch the recording of your “performance.” A mirror of our tech-obsessed society, the installation is about simulacra, about a performance we never experience directly but discover through its representations.

Félix Luque, Damien Gernay & Vincent Evrard, Perpétuité 4

The exhibition closes with Perpétuité 4, a triptych that uses found footage to depict the production of cars, from manufacturing to crash test to driving in cities. Every stage is devoid of humans. The “dark factory” only requires robotic arms to assemble vehicles, the crash tests use dummies and remotely operated cars, the driving around urban areas is autonomous. The experience is accompanied by an algorithmic music composition. Infinite, it emphasises the idea of a perpetual, automated cycle with no beginning and no end. As if the Earth and its resources were not limited.

Watching the hypnotic images, i didn’t think about progress, technology or AI. I thought about ghosts and about a system that doesn’t need citizens and ecosystems. Just customers and minerals.

More images from the exhibition:

Félix Luque Sánchez, Flags, in collaboration with D-E-A-L, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Nicolas Torres, Le Motel, Flora, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez, Nicolas Torres, Le Motel, Flora, 2025

Félix Luque Sánchez in collaboration with the Lycée Émulation Dieppoise, T-Slot, 2025

La Société Automatique, an exhibition by Félix Luque Sánchez, in collaboration with Vincent Evrard, Damien Gernay and Íñigo Bilbao Lopategui, remains open at iMAL in Brussels until 15 February 2026. Choreography and performance: Mercedes Dassy / Music: Le Motel & Ben Bertrand. The exhibition is taking place in the context of EUROPALIA ESPAÑA.