The KOSMICA: Full Moon Party took place last month as part of the Republic of the Moon exhibition programme and that means that I’m ridiculously late with these notes. Kosmica is The Arts Catalyst‘s evenings of performance and conversations for the ‘cosmically curious.’ I’ve attended a couple of Kosmica events in the past and this one was as exciting as ever.

Space scientist Lucie Green is an expert in the sun but she gave a wonderful presentation about the magnetic bubble that surrounds and protects the earth from the radiation of the sun and about how the moon is electrically charged, Dr Jill Stuart focused on space politics, Tomas Saraceno talked about cities that are lighter than the air, Kevin Fong asked us to reflect on how past expeditions might actually belong to the future.

Sue Corke and Hagen Betzwieser from WE COLONISED THE MOON presented the largest Moon smelling session ever done on our planet. It was hilarious and it didn’t smell nice. My wool sweater is not thanking them.

London based improvisation band Orchestra Elastique live scored Georges Méliès’ A trip to the Moon.

All the talks are online. I enjoyed all of them but i wanted to spend more time on the most ‘political’ ones so i’m writing down below some notes and links from Kevin Fong and Jill Stuart’s presentations.

Kosmica Full Moon Party Part 6, Jill Stuart

Dr Jill Stuart is a Fellow in Global Politics at the London School of Economics, and reviews editor for the journal Global Policy. She researches law, politics and theory of outer space exploration and exploitation. Her interests extend to the way terrestrial politics and conceptualisations such as sovereignty are projected into outer space, and how outer space potentially plays a role in reconstituting how those politics and conceptualisations are understood in terrestrial politics. ,

Stuart talked about the long history of outer space law and more specifically about ‘Who owns the Moon?’ (which she calls the Muuuhn)

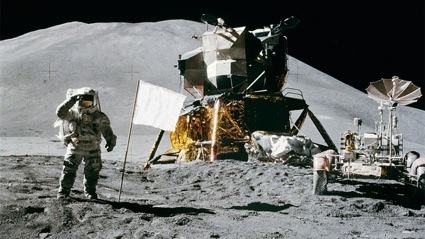

We all know that iconic image of Neil Armstrong planting a flag 1969. Did the gesture imply that the United States can claim any kind of ownership over the moon? Who owns the moon exactly?

The answer is a combination of ‘no one’ and ‘everyone’ owns the moon.

No One because The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 says that outer space (which obviously includes the moon) cannot be ‘appropriated’ by any national State for sovereign purposes.

Everyone because the same treaty states that outer space is the province of all mankind.

The treaty was widely ratified and is still today accepted as being doctoring.

David Scott salutes the American flag during the Apollo 15 mission. Great Images in NASA Description, NASA photo AS15-88-11863

David Scott salutes the American flag during the Apollo 15 mission. Great Images in NASA Description, NASA photo AS15-88-11863

All the American Flags On the Moon Are Now White (via Gizmodo)

All the American Flags On the Moon Are Now White (via Gizmodo)

Larissa Sansour, A Space Exodus

Larissa Sansour, A Space Exodus

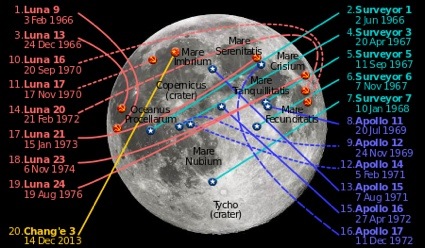

Now another interesting issue Stuart raised was the number of flags on the moon. The US chose to put a US flag on the moon, rather than some sort of global flag. But it turns out that there are more than one US flag on the moon. 6 US flags were delivered by humans on the Appolo mission.

And it wasn’t just the US who got ‘flag happy’. Four other countries had flags delivered even though it didn’t have legal significance in terms of appropriation. Russia, China, India and the European Space Agency also have flags up there. Russia and China have soft landed on the moon and delivered flags. The other delivery method is to crash something on the moon that bears a flag.

Imagemap of the locations of all successful soft landings on the Moon to date

Imagemap of the locations of all successful soft landings on the Moon to date

Speaking of crashing into the moon: the moon is at the center of many geopolitical interests. In the 1950s, the United States were thinking about landing on the moon to show off their technological prowess (in particular to the Soviet) but a top secret study revealed that the US also briefly considered nuking the moon, instead of landing on it. The fall off would enable scientist to study the geological make up of the moon and the flash from the nuclear explosion would create a difference on the surface of the moon that could be seen back on earth.

The first Apollo mission carried a plaque which still stays on the moon and says “Here men from the planet earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969. We came in peace for all mankind.”

That same July 1969, the US was also investing in the Vietnam war. How do you reconcile this idea of coming ‘in peace for all mankind’ with bombing Vietnam?

The last human mission on the moon was in 1972. Since then there has only been some soft landing.

Moon, a 2009 British science fiction film co-written and directed by Duncan Jones, was about a man on a three-year solitary stint mining helium-3 on the far side of the Moon

Moon, a 2009 British science fiction film co-written and directed by Duncan Jones, was about a man on a three-year solitary stint mining helium-3 on the far side of the Moon

Since then, one of the big issues that have emerged is mining. Is mining the moon legal? Is it even desirable?

The moon might have helium-3 which could be a fuel to travel from the moon to other planets. But is it legal? The Outer Space Treaty is a bit ambiguous in that regard. It says that any activity should be carried out for the common heritage of our kind and benefit all people and all countries. The treaty therefore advises to redistribute anything that should be gained from mining. However, the fifth treaty (1979) sought to clarify some of these issued but mostly failed as only very few countries ratified it.

In 2002, China stated their moon intentions. They included establishing a base on the moon for the purpose of mining, they said that the resources that they extract would be for the benefit of humanity. What does that mean?

Stuart believes that mining will be a big issue in the future.

Another problem of the main Outer Space Treaty is that they are rooted in a state-centric language. Many people are curious about the companies that sell plots of land on the moon and other celestial bodies. The outer space treaty says that no nation state may lay claim on a celestial body. So does that give green light to individuals, corporations or private partnership? Stuart doesn’t believe so. We are only now learning to deal with the fact that it’s not just states that are planning to go into outer space. Wealthy individuals and corporations are looking at it too. Outer space law still have to catch up with that.

Kosmica Full Moon Party Part 5, Kevin Fong

Kevin Fong, a space medicine expert and the co-director of the Centre for Aviation Space and Extreme Environment Medicine (CASE Medicine), at University College London, talked more generally about exploration.

There aren’t any wide space left to explore on the surface of the Earth. A hundred years ago, however, there were still many places where humans had never been (South Polar region, some of the highest mountains, etc.) Now we’ve explored the earth, the air, we’ve even been to the moon. What happens next?

We’re a bit blasé about the future. Going to the moon doesn’t look like a big deal anymore now.

But in context, going on the moon was a terrible thing to do. Millions of American tax dollars were spent, 5% of the country GDP, were spent on sending people into space when people (in and out of the country) were starving and unable to afford healthcare.

John F. Kennedy at Rice University (“We choose to go to the moon in this decade”), September 12, 1962

There are some myths regarding the public attitude about moon exploration. It is said that everybody was really into it in the 1960s and then everyone lost interest. But in fact, research shows that approval for the Apollo mission never reached 50% amongst members of the U.S. until they landed on the moon and then approval reached a high point for a couple of weeks and then went back down again. So people weren’t so enthusiastic about sending men to the moon.

Why did we go to the moon? We already know that it was a surrogate battlefield for a war that could not be fought in any other way. And some of the people who were the architects of Apollo had actually been around during some of the most atrocious moments of the 20th century. And if they didn’t take part in it, they were certainly aware of it and did nothing to stop it. Some of them even probably were ‘card-carrying nazis’ until the day they died. Yet, we celebrate them in a revised history. And some of the research actually emerges from the V2 rocket. We look for vision and inspiration when actually the mission comes from some of the darkest pages of human history.

Was Apollo worth it? Someone said that Apollo was an aberration and that it was a piece of 21st century that was dragged into the 20th. Which is why we never went back. It was just too hard to do and it was too soon. And that is the way that most explorations are done.

We see romanticism behind most explorations. According to Fong, the exploration of any time doesn’t make sense to the rational people of the same time. When you look back at the great explorations of the past, it’s the same story. It’s some imperial power leading their effort through their military, usually at great expense and great risk of human life.

An illustration of this theory is Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe between 1518 and 1522. In 1518, Ferdinand Magellan can’t convince Portugal to support his expedition project so he goes to rival Spain and sails with 5 ships and about 280 sailors. The whole expedition is a real ordeal. 3 mutinies, 4 ships lost, Magellan dies before the completion of the expedition and the only ship that manages to get back to Seville is sailed by only 18 men. In fact, Magellan had not even intended to circumnavigate the world, but to find a secure way to the Spice Islands. Yet, we remember this episode as being a glorious page of history and we recognise it as an important stepping stone. But the men at the time probably thought that too high a cost had to be paid. To Fong, you can only love the exploration of a moment so that people of the future will vicariously enjoy it on your behalf later.

So is this the point when human exploration stops? When we come to realize that it is too expensive and comes at too high a human price?

The Moon is the furthest point we’ve ever been from the earth. How will history see project Apollo? We will either see it as we see Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe as an important step along a much longer journey or we will see it as we see the pyramids, an amazing achievement but “Why the hell did they do that?”

Image on the homepage from Moon, a 2009 British science fiction film about a man on a three-year solitary stint mining helium-3 on the far side of the Moon.

Previously: Should we colonize the Moon?