Julian Bleecker is a well-known man to the Internets – my search on Flickr for a portrait of him yielded over 500 results (photo snatched from Ti.mo‘s photostream).

Julian Bleecker is a well-known man to the Internets – my search on Flickr for a portrait of him yielded over 500 results (photo snatched from Ti.mo‘s photostream).

This might be because of his manifold activities in the realm of electronic media, including teaching at USC’s Interactive Media Division, blogging at Techkwondo, writing manifestos about Why Things Matter, lecturing about the CO2 production of avatars, researching the near future with accomplice Nicolas Nova or his stereoscopic collection of funny bikes.

Time for an interview to find out about the bigger picture and where it all might lead to in that near future.

Julian, what does a blogject do differently from an object?

Well, a blogject is like an object with social tendencies, worldly. It wants to be more than inert, more than a physical object. It has a tendency to be unique and contribute to conversations in specific, situated contexts. And they do this because they are net-savvy, and know all about the latest and greatest of sharing and circulating information in the connected world.

Objects — the more inert cousin of blogjects — aren’t necessarily net-savvy. They certainly are social in lots of meaningful ways. You can get an object that inspires very social action, conversations or activities — a board game or well-designed chair, for instance. Blogjects can be as socially engaged as objects, only they do so with the full-force and power of what digital content dissemination techniques provide — feeds, aggregation, tagging, etc.

Blogjects are social in the way they address topics of concern. They’re clever machines, but not artificial intelligences. They’re like a lens on the physical, 1st life world, taking advantage of the wonderful world of sensor technologies. Blogjects are objects for wired, digitally networked societies. Over time, they’ll become responsible for laminating 1st life and 2nd life in meaningful ways. And I think the ultimate responsibility is to force awareness of life- and world-threatening issues. At their best, blogjects make us aware of the unfolding tragedies that surround us everyday. And their power comes from the ability of their insights to circulate at the speed of the network.

Laminating the lives is an interesting point. Let’s look a bit more closely at the current interactions between those worlds: so we have objects with social qualities, thanks to their net-savviness. On the other hand – so it seems – there’s a movement to create the virtual realities we had been told about for decades, with Linden Lab’s Philip Rosedale talking about “digitizing everything”. Are those two discrete notions, or are they part of one process and if so, what kind of reality would it possibly lead to?

I think this notion of digitizing everything is a bit misguided. It presumes that most everything should be digital, without consideration as to what it means to have particular human experiences or activities transferred into digital form. It’s a kind of digital-era imperialism or evangelization of the database gospel — “if it can be structured as data, put it on the Internets” — or something. It has so many things wrong about it, beginning with a lack of any sort of critical inquiry as to what it means, or why one would think it worth while, for instance, to have make digital shopping malls in Second Life.

The (always deserted) American Apparel store in SL

The (always deserted) American Apparel store in SL

If the project of the digital age is to make everything that we have in “1st life” available in 2nd life, then I think we’re on the wrong path. Laminating 1st life and 2nd life isn’t about creating digital analogs. It’s about elevating human experience in simple and profound ways. This blogject project is an early manifestation of what I think we will start seeing as clever tinkerers experiment with creating meaningful bridges between 1st life and 2nd life in which ethics precedes doing something “just ’cause” it’s possible. And those bridges come firstly in very simple expressions of 1st life activity in 2nd life, or 2nd life activity in 1st life.

Bruce Sterling has a great turn-of-phrase I once heard him speak — “we will get the future we deserve.” And in this case it means if we want Gap Stores, shopping malls and advertising signage in Second Life, that’s what we’ll get. But I think many people want something that will yield more habitable worlds, not more efficient ways to market and get people to buy crap. We could create impacts and shape thinking and behavior with digital networks, particularly ones that speak to 1st life. We can create bridges that capture, share and disseminate the current, day by day state of the thinning northern ice cap. We can create a 1st life / 2nd life bridge that makes this condition as present, as impactful and as resonant as a dripping faucet in the next room, rather than an abstraction only occasionally brought to our mind through a newspaper article or cocktail party conversation.

But couldn’t it be that one of the “simple expressions” of the 1st life that first bridge over, might be shopping? No capitalism-bashing intended here, but isn’t it just astonishing to what extend the simple fact that every object in SL is also a potential commodity seems to boost the attractiveness of the system for very different groups of users?

Yeah, not really astonishing — expected is probably the more precise description. Most digital network participants are well-rehearsed when it comes to circulating culture through commodity exchange. But we see so many other forms of making culture online that take advantage of the Internets’ capacity to be a relatively safe zone for grand-scale social experiments — like the fascinating experiments that I barely understand in which digital kids acquire as many possible social network friends as possible. That’s an experiment in acquisition — a kind of accumulation of social capital, I suppose.

It’s possible to imagine that what was really going on 10 years ago with the Internets was a desperate attempt to orchestrate a new social experiment — one that could take our clunky, dinged, sputtering, oil-spewing, blood-soaked attempt at Enlightenment via Democracy and become humanity’s last bid at forming a more playful, life-affirming world. The Internets went askew as soon as they got turned into a capital accumulation experiment, which fracked us all. It’s the deadly “quarterly results” myopia of corporations that limited the foresight to see what the Internets could have become. To have ended up with shopping carts, a collapsed ecosystem and Fox News Online is pathetic. Certainly there are pockets of activity where experiments continue to explore how free-trade in culture can yield more habitable worlds. Time is short, though, and there are plenty of bottom-up culture haters out there who would like nothing more than for the MPAA and Rupert Murdoch to take over and define what the Internets become.

The experimentation part is a really interesting one. Both individuals and companies seem to use the “Internets” to experiment with possible 1st life schemes. Then you have weird 2nd life things like the copybot happening, a digital paradigm applied to the digital simulation of a physical world which caused quite a drama. Could you imagine other forms of possibly equally playful interactions between the lives?

Finding compelling ways to make 1st life legible and meaningful in 2nd life is probably one of the most fascinating, provocative experiments of the digital networked era. Social networks, meet-up sites, match making online — these are just Proterozoic experiments that take existing social practices and make them network-enabled. I want to find experimental vectors that move towards a set of experiences and provocations that link 1st life and 2nd life so that there is a kind of effortless divide, so that it is possible to occupy both simultaneously. Not by having a connected phone so that you’re wandering down a gorgeous, baroque alley in Vienna while staring at your mobile screen, trying to get Google Maps to figure out where you are — I imagine something much more translucent and less literal.

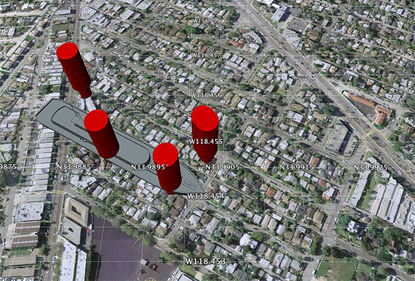

Battleship: Google Earth, a 1st/2nd-life mashup

Battleship: Google Earth, a 1st/2nd-life mashup

For instance, mobile computing as it’s presently conceived makes a rather literal representation of 2nd life in 1st life. The canonical “mobile email” is just such a knee-jerk bridge. We know all about email in 2nd life. How do we make it part of our mobile life? Make a software email client for the mobile phone. From the perspective of innovation and creativity, I think that is pragmatic, convenient, practical rubbish. It’s one of the cruel jokes of the mobile phone carriers, to say that we’re going to live untethered lives.

The kinds of experiments that will help us imagine and create a more habitable, playful world are far more provocative than what anyone trying to make their quarterly numbers will offer. These experiments must question conventional assumptions, find ways to encourage and appreciate whimsy, and recognize that pragmatism got us the world we have now. By experiment I mean a kind of serious, creative endeavor that is technoscientific in spirit. By experiment I also mean that I’m trying to find a way to tell a story about possible near future worlds, or create imaginary worlds through technological instruments. Filmmakers have been telling visual stories about imagined, fictional worlds for a century — and the best of these stories help us think through worlds we presently occupy, and help us make meaning about the condition of certain corners of life. In the very, very best of films, they help us to find the courage to make manifest changes to our worlds so as to make the world a more habitable, life-affirming place. Science-fiction literature does this as well, of course. Something I learned while pursuing my master’s in engineering and doctorate was the ways in which technologies are instruments for making meaning — they’re fully social and cultural. In this way, they can be used to make and circulate culture by their very design. Discovering that you can make a technology that helps author an imaginary, near-future world was the first page of a new chapter for me. I’m much less interested in experiments that tell stories about world’s with e-mail on a mobile phone, so I stay away from those practicalities. The kinds of experiments I do are ones that tell stories about worlds that may be, or world’s I wouldn’t mind occupying myself, or cautionary stories about possible near futures that make me nervous. If I could write or make film, that may be the way tell these stories. I’m an electrical engineer and have a fluency with the idioms and grammars of computer science, so I make devices to articulate aspects of these near-future worlds.

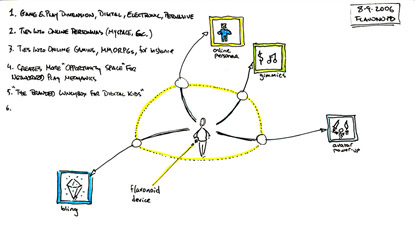

Sketch for Near Future Lab’s project Flavonoid

Sketch for Near Future Lab’s project Flavonoid

I’m elbow deep in a set of experiments of the non-pragmatic, non-practical variety, but one’s that I hope can be understood to evolve and shift the relationship between 1st life and 2nd life, creating new lenses through which each is represented within the other. One experiment I’m conducting with my good friend Nicolas Nova through our earnest Near Future Laboratory project is to turn critters — specifically, in this case, a pet dog — into interaction partners in digital worlds. We’re imagining what a near-future would be like if the partners with whom we interacted were the other occupants of our world, such as pets. We’re making a dog toy for a friend’s one-eyed dog that will manipulate the actions of a Dwarf in World of Warcraft. So there you would have a somewhat playful provocation — pets playing in World of Warcraft. The experiment is less about actually creating a pet playable version of that very complex online game — we don’t suppose for a minute that a dog can play World of Warcraft in the sense of pursuing the goals of the game or comprehending the through-line. But certainly a dog can control a WoW character to the same degree that they can control and manipulate a favorite rag-doll chew toy. This is a test balloon, floated to begin imagining-through-construction a context of participation between pets and humans in the new networked age.

So you have an almost social approach to the technoscientific projects you’re creating in the way that you want them to have a certain impact on our imagination. How does this position relate to the notion of critical design? And, since you mentioned the power of fiction, how important is it for you that designs and devices actually exist and work in order to be powerful statements?

I’ve learned a lot from Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby‘s work. The most important lesson is finding out that it is okay to make objects and devices speak with a critical voice, or to have some say over their conditions of use. I have spent years developing the knowledge to construct technological instruments while doing my undergraduate studies in electrical engineering and building hardware and software as a professional engineer. And then many more years in graduate studies learning how to think and write about how technologies are imbricated with culture. What critical design allows me to do is construct technologies that help me, and others I hope, see just how thoroughly technology is culture. And of course once you can appreciate that you can recognize that technology is mutable and doesn’t have to be the way it is. This is more apparent today, particularly with the energy behind this latest wave of DIY sensibilities.

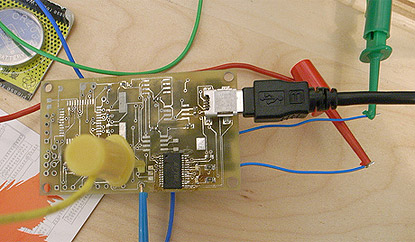

Related is this idea of the theory object as my colleague Tara McPherson has taught me — an object through which one can come to understand what the object is here for, how it works, how it can work differently. This is much like Rich Gold’s Evocative Knowledge Objects. So, not only is the finished, designed object of interest, but so too is the process of its construction, which you must ruthlessly capture and document because every step of the process has something important to say that’s part of the critical voice of the design — from the initial sketches, to choosing parts, to accidentally bricking an expensive component. For me, there is a critical voice both in the completed design and in the craft work of construction. I think it’s important to avoid opaque design. As a consequence, I perhaps make others suffer because I tend to over-document my construction projects and designs. But, I think the craft work illuminates the process in a really valuable, authorial way. It’s like hearing the voice of the designer figuring out what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, and then why they did it in both practical terms as well as design and cultural theoretical terms. And of course actually constructing the design is crucial — you can’t just have a theory without going through the trouble of working from your intuition or dreams, through the hands-on execution and craft work, to the point where you decide to put a bit of punctuation on it and call it done. It’s fun to take an idea and then actually realize it — it’s like making little mini-dreams come true.

Documenting the often tedious process of how ideas become reality

Documenting the often tedious process of how ideas become reality

Where is the ideal place to live for those creations so that they can reach and touch many people? Is it in the form of some sort of product (which may also be re-built DIY-style using your documentation) or in the context of exhibitions or festivals? At Transmediale, Olia Lialina brought up the notion that being featured on blogs like this one might sometimes suffice and, in a way, even become one goal in itself. How would you like your projects to be received?

The ideal place would be as close to the imagination as possible, because what I feel art-technology does best is encourage stories about near future worlds that we may actually want. Sometimes those stories evolve from ironic devices that remind us about aspects of the networked age that are not so fantastic. Most ironic device art really only can exhibit in design galleries or as part of the art-technology festival or blog circuit. But as DIY sensibilities take hold more firmly, it’s possible to imagine that there might be an audience who want to own what they see at festivals or read about in a blog, so they can live with what they were only able to imagine.

Dear Julian, thanks for the interview.