Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

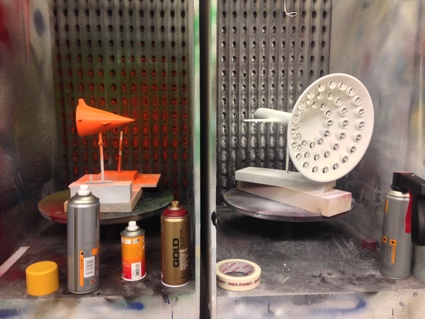

X-1SB and Boomjet models receiving initial coats of paint

X-1SB and Boomjet models receiving initial coats of paint

High-Speed Horizons is another of my favourite works exhibited at the graduation show of the Royal College of Art earlier this month.

One of the models in the exhibition space

One of the models in the exhibition space

In this project, Design Interactions graduate Tim Clark plays with the language and history of aviation, offering us a trip into critical and speculative visions of alternative energies.

Aviation, says the designer, has always been viewed as a test bed for radical new ideas and visions to reshape culture, politics and economics on Earth and far beyond it. Some of these dreams of alternative futures became reality and even transformed other areas of life (especially in military or space exploration contexts), while others were aborted because of political, economic or environmental pressures.

Tim Clark tapped into this fascination for unrestricted innovation to design a series of airplanes that investigate the possibility to ditch environmentally damaging fossil fuels in favour of sonic booms and nuclear power.

Bell X-1. Image Smithsonian Air and Space Museum

Bell X-1. Image Smithsonian Air and Space Museum

Chuck Yeager Breaks the Sound Barrier, X-1, 1947. Newsreel from 1948

The most experimental and speculative aircraft research is often classified. An example of this is the American X-Plane. Started after WW2 and still in operation today, the program conceived a series of experimental planes and helicopters and used them to test new technologies and aerodynamic concepts.

The first of American X-Plane model, the Bell X-1, was the first aircraft to break the sound barrier in level flight in 1947. This breakthrough opened up a new field of supersonic research and led to experimentation in aerodynamics and new propulsive systems.

Supersonic speed travel is accompanied by an explosive ‘bang’ sound called sonic boom. These sonic booms also generate enormous amounts of energy. In theory they could thus power planes with an efficient, green and sustainable energy source.

But sonic booms are one of the main reasons why supersonic airplanes never became more commonplace. In several countries, the law prevents aircrafts from flying above Mach 1 due to the shock wave’s auditory and vibrational disturbance.

Limiting the impact of sonic booms is a current concern of the aviation industry as many are dreaming of a new supersonic age. But if it is to be more successful than the last one (the Concorde required high quantities of fuel), a supersonic plane would need an energy source free from the influence of global affairs, politics and planet scarring infrastructure. Something that we can quickly produce and have complete control over — like sonic booms.

Tim Clark, The X-1SB, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The X-1SB, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The X-1SB, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The X-1SB, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, High-Speed Horizons (X-1SB being airdropped by B-29 Duo mothership. Oil on canvas by Michael Lightfoot), 2015

Tim Clark, High-Speed Horizons (X-1SB being airdropped by B-29 Duo mothership. Oil on canvas by Michael Lightfoot), 2015

The X-1SB, aka the “Sonic Sundae”, is Clark’s counterhistorical research aircraft designed to test the feasibility of this sonic boom propulsion. Its cone shape design is the combination of a .50 caliber bullet (an object know to be stable while breaching the sound barrier) just like the design of its predecessor the X-1 aircraft, and the shape of the shock wave created by an object traveling faster than sound.

The front of the aircraft features a housing for an interchangeable triangular spike used to test how different shapes could create potentially optimized shock waves to use for propulsion.

And because Clark’s work is counter historical, Sonic Sundae and Boomjet (more about that one below) were to have existed before any of the anti-noise laws were to have been instituted.

He told me: I am suggesting that in a sonic boom powered world those laws would not exist because the ability to travel with that type of greener propulsion would probably be more beneficially economically than instituting the flight restrictions. In this case the benefit of the disturbance would outweigh the desire to limit the noise.

Conceptual drawing of a supersonic biplane. Image: Christine Daniloff/MIT News based on an original drawing courtesy of Obayashi laboratory, Tohoku University

Conceptual drawing of a supersonic biplane. Image: Christine Daniloff/MIT News based on an original drawing courtesy of Obayashi laboratory, Tohoku University

Anyway if we were to live in true supersonic age these restrictions would need to be changed/relaxed anyway sonic booms or not. The big research in limiting the sonic boom now is finding a way to make a wing design that will create little to no noise when it breaks the sound barrier so it does not disturb people below the plane. Amazingly this question was answered over a decade (1935) before we even broke the sound barrier (1947) by Adolf Busemann who suggested a supersonic biplane design where the two wings would be used to cancel the other wave out.

It’s crazy to think a supersonic jet would resemble a biplane from the 1920s but it would probably be the best solution and it was theorized way before it ever would be seen as a problem which is amazing. MIT just did some research into it in the last year or so and it would totally work and might be quite viable.

Tim Clark, B-29 Duo, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, B-29 Duo, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Because of its large rear circumference, the X-1SB cannot fit under the fuselage or wing of a larger aircraft for taxiing and takeoff. The B-29 Duo “Double Mama” has thus been designed to be its carrier aircraft of choice.

An F/A-18 Hornet breaks the sound barrier in the skies over the Pacific Ocean, 1999. Image Ensign John Gay, U.S. Navy (via wikipedia)

An F/A-18 Hornet breaks the sound barrier in the skies over the Pacific Ocean, 1999. Image Ensign John Gay, U.S. Navy (via wikipedia)

Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, The Boomjet, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

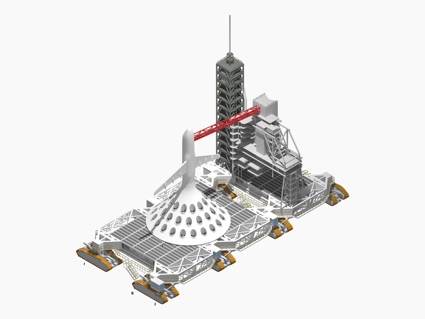

Boomjet on mobile aircraft crawler. Computer rendering by Tim Clark

Boomjet on mobile aircraft crawler. Computer rendering by Tim Clark

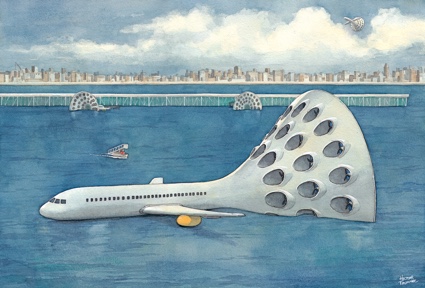

Tim Clark, High-Speed Horizons (Boomjet taxiing at water-based airport. Watercolor on paper by Hector Trunnec), 2015

Tim Clark, High-Speed Horizons (Boomjet taxiing at water-based airport. Watercolor on paper by Hector Trunnec), 2015

Another of Clark’s designs, the Boomjet is a sonic boom-powered commercial transport that sustains its flight by driving 47 propellers from the pressure energy released by the aircraft as it travels faster than the speed of sound. The sonic boom transport vehicle stores excess energy for use during takeoff which can be vertically or from water depending on location.

Clarks then looked at another source of energy that could disentangle aviation from its dangerous relationship with fossil fuels: nuclear energy.

The Convair NB-36 in flight, with a B-50. Photo: USAF – U.S. Defenseimagery.mil photo no. DF-SC-83-09332 via wikipedia

The Convair NB-36 in flight, with a B-50. Photo: USAF – U.S. Defenseimagery.mil photo no. DF-SC-83-09332 via wikipedia

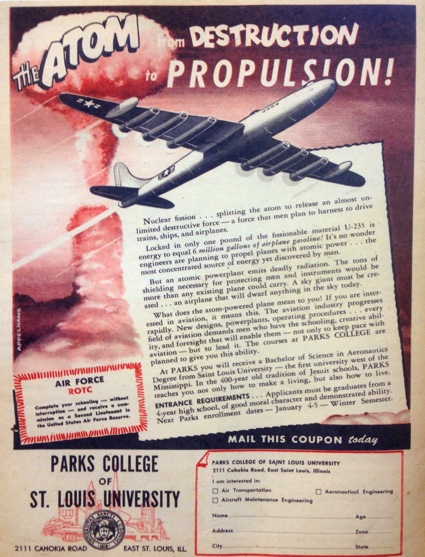

Advert from November 1951 AIR TRAILS magazine promoting the promise of nuclear power as an unlimited energy source for flight. Image from Secret U.S. Proposals of the Cold War: Radical Concepts in Factory Models and Engineering Drawings by Jim Keeshen

Advert from November 1951 AIR TRAILS magazine promoting the promise of nuclear power as an unlimited energy source for flight. Image from Secret U.S. Proposals of the Cold War: Radical Concepts in Factory Models and Engineering Drawings by Jim Keeshen

During the cold war both the USSR and the USA had an experimental nuclear aircraft program. While the risk was high, nuclear power promised an aircraft with theoretically unlimited range capable of constant flight.

Only two known nuclear aircraft that have been fully built and tested. The NB-36H was America’s nuclear-powered aircraft. Refitted for this new propulsion system after it was damaged in a storm and deemed unfit for combat, the aircraft featured a direct phone line to the President of the United States that was to only be used in the event of an incident. The NB-36H completed 47 test flights between 1955 and 1957 over New Mexico and Texas. It was scrapped in 1958 when the Nuclear Aircraft Program was abandoned.

The Soviet Union’s aircraft, the Tu-95L, was based on the Tupolev Tu-95 strategic bomber and missile platform. First flown in 1952, the plane is still in operation today and Russia sometimes flies it in close proximity of the airspace of other European countries in order to affirm its military presence.

The nuclear variant of the TU-95 flew from 1961 to 1965.

Both the USA and the Soviet Union had ambitious plans for their second nuclear-powered aircraft but due to environmental concerns, political pressures, and rumors that the other side called off their research both projects were shelved.

While the risk of a nuclear accident is deemed too high in aviation, we have nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, submarines and 11% of all the world’s electricity being based on nuclear power.

Tim Clark, Air Laissez-Faire, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, Air Laissez-Faire, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, Air Laissez-Faire, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Tim Clark, Air Laissez-Faire, High-Speed Horizons, 2015. Photo by Juuke Schoorl

Designer applying the 500+ dry transfer window decals and nuclear logo decals to the Air Laissez-faire model aircraft

Designer applying the 500+ dry transfer window decals and nuclear logo decals to the Air Laissez-faire model aircraft

Clark proposes to update to our times a technology that looked promising at the height of the Cold War. And the ones willing to bankroll the experiment might not be countries but technology companies which are already at the forefront of some ambitious innovative projects (Richard Branson and Virgin Galactic for example.) Because these tech companies are increasingly under governmental scrutiny so that they don’t get out of control, they might also take to the sky to further innovation free from the restriction of regulation, utilizing the energy source historically clouded by politics to sustain continuous flight and prove that anything is indeed possible through innovation. An inspiration for the idea is Blueseed. This “start-up community on a ship” proposes to gather hundreds of immigrant entrepreneurs on a floating startup city in international waters off the coast of San Francisco and have them live and work undisturbed by the burden of national boundaries and government regulations.

Clark’s mini Silicon Valley on air is called Air Laissez-Faire. A nuclear power plant on board of this self-piloting aircraft would provide virtually limitless amounts of continuous propulsion, while a crew made of nuclear physicist, chemical engineer, radiation consultant, and other figures would ensure safety on board. The mega plane presents satellite and radar communication equipment for remote business meetings, all necessary business facilities as well as a landing space on its rear wings that allow small ‘commuter aircrafts’ to whisk entrepreneurs from and back to major business centers.