Every society is a high society. From morning coffee in European cities to kava in Pacific villages, betel nut in Asia to coca leaf in the Andes, the rituals of drug use are everyday and universal, and stretch back through centuries.

The Wellcome Collection, which explores the connections between medicine, life and art in the past, present and future, has quickly become one of my favourite cultural venues in London. Their recently opened exhibition, High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture, explores the history of narcotics and -maybe more interestingly- the perception we developed of it through time.

Although it doesn’t seem to put forward any moral judgment, the exhibition asks us to leave our prejudices at the door and examine the facts, theories and arguments before we decide on which side the balance between right and wrong should tip.

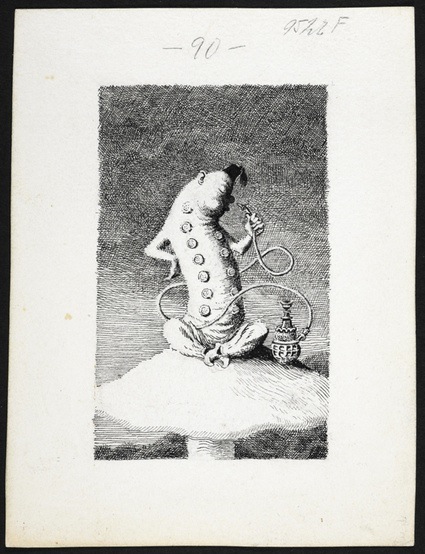

Illustration by Mervyn Peake for Carroll’s ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’

Illustration by Mervyn Peake for Carroll’s ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’

While the exhibition highlights the damaging effects of drugs and of the violent drugs trade, it also reminds us that several cultural icons have waxed lyrical about the joys of mind-altering substances. Charles Baudelaire wrote about his experiences of hashish and opium in Les Paradis Artificiels. Robert Louis Stevenson, would have written The Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde while he was under the influence of a hallucinogenic drug similar to LSD. In The Sign of the Four, Dr Watson asked literature’s most renowned intravenous drug user Sherlock Holes:

“Which is it to-day,” I asked, “morphine or cocaine?”

He raised his eyes languidly from the old black-letter volume which he had opened.

“It is cocaine,” he said, “a seven-per-cent solution. Would you care to try it?”

Substances that many of us consume freely today – alcohol, caffeine and tobacco – have all been criminalized in the past or remain illegal in some parts of the world. A tract published in Leipzig in 1707 berated early adopters of tea for “drinking themselves to death”.

Bayer Company Heroin, Glass bottle and contents, Bayer, Germany, around 1900. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain

Bayer Company Heroin, Glass bottle and contents, Bayer, Germany, around 1900. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain

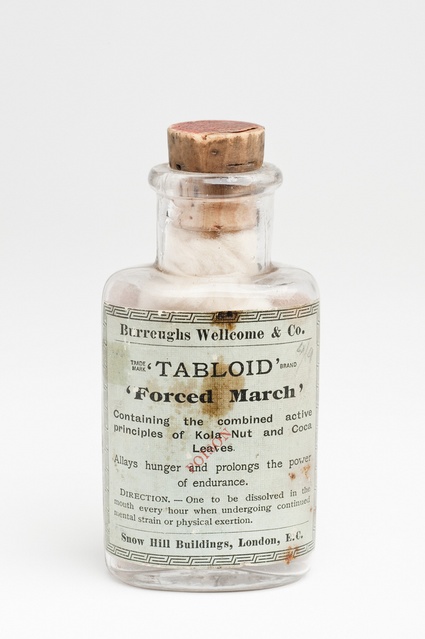

Tabloid brand Forced March, Glass bottle and contents, Burroughs Wellcome, England, 1897-1924. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain

Tabloid brand Forced March, Glass bottle and contents, Burroughs Wellcome, England, 1897-1924. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain

Correspondingly, substances which, today, we regard as harmful used to be prescribed by doctors for their health benefits. Early 20th century Western mothers treated their coughing child with heroin syrup. Coca-Cola got its name for the tiny doses of cocaine it contained during the first few years of its commercial life.

However, fears over the health problems caused by drugs quickly emerged and by 1961, a United Nations convention on narcotic drugs led to their criminalisation. The general ban has not met with much success since today, the illicit drug trade is estimated at $320 billion a year – making it the third biggest international market on the planet, after arms and oil.

A few highlights from the exhibition:

A section of the exhibition is dedicated to self-experimentation, the affects of recreational drugs are indeed best described by their users:

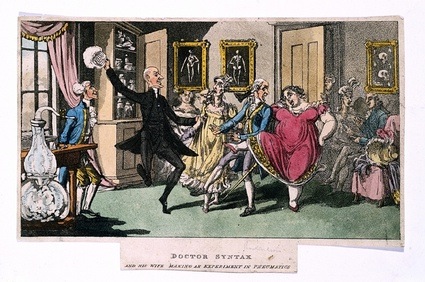

T Rowlandson after W Combe, Doctor and Mrs Syntax with a party of friends, experimenting with laughing gas, coloured aquatint, 1823

T Rowlandson after W Combe, Doctor and Mrs Syntax with a party of friends, experimenting with laughing gas, coloured aquatint, 1823

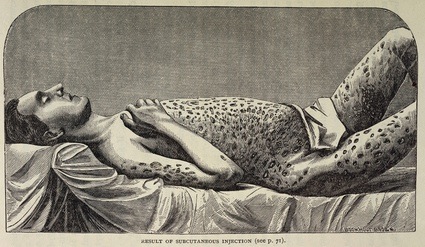

When morphine for injection was first introduced it was often injected just under the skin. This could lead to abscesses and scarring as shown here. This ‘morphinomaniac’ subject was a male nurse pictured shortly before his death:

A mescaline experiment on human by Dr Humphrey Osmond and broadcast on the BBC in 1955:

Of course, experimentation was also performed on animals. High Society showed a video documentation of Canadian psychologist Bruce Alexander’s Rat Park, a late 1970s experiment which showed that rats living in a happy environment consumed less morphine than the ones confined in small cages.

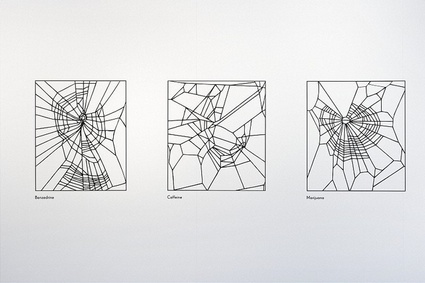

Nasa spider experiment, conducted in 1993, studied the webs of a spider after it had imbibed three different substances, cannabis, benzedrine and caffeine. The researchers found that caffeine, more than any other drug, caused the creatures to spin the most deranged webs.

NASA experiments on spiders. Image Wellcome Library, London

NASA experiments on spiders. Image Wellcome Library, London

View of one of the exhibition’s rooms, featuring a massive bong statue spanning the length of the space.

View of one of the exhibition’s rooms. High Society, Wellcome Collection. 11 November 2010 – 27 February 2011

View of one of the exhibition’s rooms. High Society, Wellcome Collection. 11 November 2010 – 27 February 2011

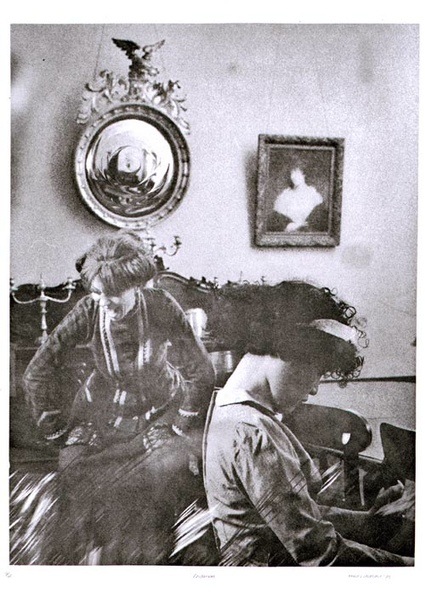

Tracey Moffatt, Laudanum, #5, 1998

Tracey Moffatt, Laudanum, #5, 1998

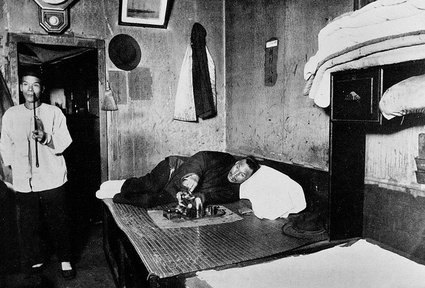

A. & E.O. Tschirch & Von Lippmann, An opium den in San Francisco. Image Wellcome Library, London

A. & E.O. Tschirch & Von Lippmann, An opium den in San Francisco. Image Wellcome Library, London

Various fungi – 20 species, including the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), death cap (Amanita phalloides) and Boletus and Agaricus species. Coloured lithograph by A. Cornillon, c. 1827, after Prieur. Image Wellcome Library, London

Various fungi – 20 species, including the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), death cap (Amanita phalloides) and Boletus and Agaricus species. Coloured lithograph by A. Cornillon, c. 1827, after Prieur. Image Wellcome Library, London

Prohibition era cigar case and edition of Al Capone “On the Spot”. Credit: Chicago History Museum

Prohibition era cigar case and edition of Al Capone “On the Spot”. Credit: Chicago History Museum

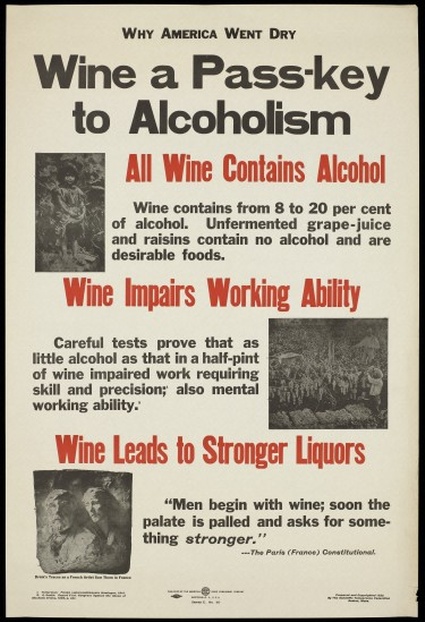

The harmful effects of wine, Scientific Temperance Federation, Boston, Mass. 1, circa 1920

The harmful effects of wine, Scientific Temperance Federation, Boston, Mass. 1, circa 1920

A whole room in the exhibition is left to Mustafa Hulusi‘s Afyon, a video installation that immerses visitors in field of colourful poppies.

Mustafa Hulusi, Afyon. Installation view in the High Society exhibition, Wellcome Collection

Mustafa Hulusi, Afyon. Installation view in the High Society exhibition, Wellcome Collection

Rodney Graham’s Phonokinetoscope installation, 2001. High Society, Wellcome Collection

Rodney Graham’s Phonokinetoscope installation, 2001. High Society, Wellcome Collection

Keith Coventry, Crack Pipes, 1999

Keith Coventry, Crack Pipes, 1999

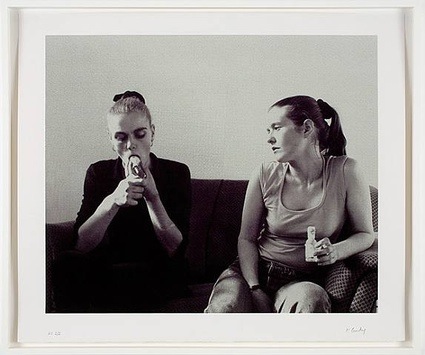

Keith Coventry, Crack Girls II, 2008

Keith Coventry, Crack Girls II, 2008

High Society is co-curated by author and historian Mike Jay and Wellcome Collection’s Caroline Fisher and Emily Sargent. The exhibition is accompanied by a book of the same name by Mike Jay. See more about it in this video by the publishers:

Image galleries.

High Society is open at the Wellcome Collection until 27 February 2011.

Previously: Exquisite Bodies at the Wellcome Collection, War and Medicine exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London, Radiographer of the day and Image of the day.