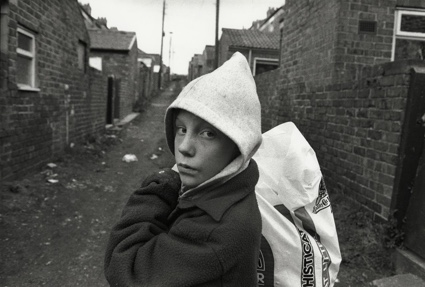

Tish Murtha, Youth Unemployment, 1981

Tish Murtha, Youth Unemployment, 1981

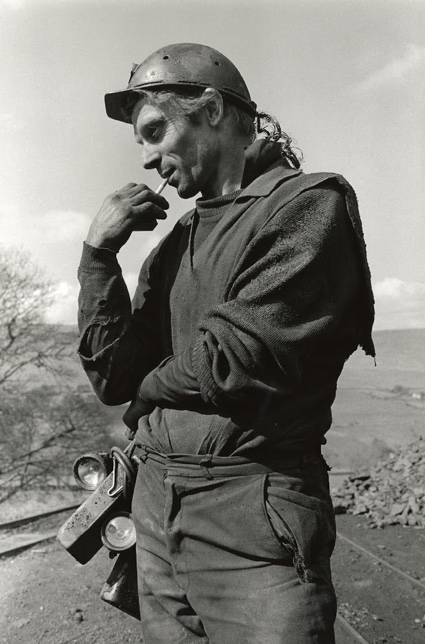

Amber Films, Launch (still), 1973

Amber Films, Launch (still), 1973

My interest for photography, working class culture and marginal communities is fairly well documented on this blog. Hence my enthusiasm when learning about the upcoming For Ever Amber exhibition.

The Amber Collective was born in the late 1960s when a group of students at Regent Street Polytechnic in London realized that their education drove them away from their working class background. Resolving to reconnect with their origins and document working class culture in photos and videos, they moved to the North East of England in 1969 and in 1977 opened Side Gallery.

Over the past 45 years, the members of the collective have been documenting the industrial and post-industrial communities living along the river Tyne, the fishermen, the shipbuilders, the people working in the coal and steel industry, but also their families, the unemployed and the marginalized communities. The result is a vast archive of photos and films that present both both artistic and historical value.

In parallel with Amber’s own film & photographic production, the collective has also been collecting and presenting to the broad public a series of classic and contemporary international documentary works, presenting similar socially-engaged concerns.

Jindrich Streit, The Village is a Global World, 1995

Jindrich Streit, The Village is a Global World, 1995

Hopefully, i’ll get an opportunity to visit the show in Newcastle before it closes. In the meantime, i had a chance to chat with author Graeme Rigby, one of the founding members of the Amber Collective. Here’s a transcript with the brief exchange we had over skype:

Hi Graeme! Why is this a good time for an Amber retrospective? Does the timing reflect a particular social moment for example?

There’s never a time in this country when an exhibition of this kind isn’t relevant!

For Ever Amber is actually part of a programme of works funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and Arts Council England to redevelop the gallery, do some digitalisation and make the works more accessible to people.

Amber Films, Shooting Magpies (poster), 2005

Amber Films, Shooting Magpies (poster), 2005

The work of the Amber Collective is rooted in social documentary, built around long term engagements with working class and marginalized communities in the North of England. I’m curious about the situation of the working class. How has it evolved over the 45 years of Amber’s existence?

That changes constantly. A lot has happened over the last 45 years because in the North East of England (and elsewhere but particularly in the North East of England) many of the industries that shaped the identity of the working class communities have closed. When these industries shut down, people send the message out that these industries are not important, that they should be eradicated.

The sense of their identity has changed considerably. This week, members of the Amber Collective worked in a school in Easington. Children there didn’t know anything about coal miners even though there is a miner banner hanging in the school hall. It is interesting and important to help children and others find their sense of identity, even if this is an entirely new identity. But having your sense of identity is important. The nature of these communities have changed. It was quite late before you saw widespread immigration in the North East of England. As a result, many of the communities were still overwhelmingly white working class but that has changed since the 2000s.

Whether they are white working class, or marginalised communities, these are people have a lot in common and their voices are denied by the mainstream.

The early members of Amber came themselves from a very working class background and felt that their education pushed them away from the places where they grew up. Instead, they wanted to celebrate their origins and the people who, so far, had mostly been used as material for jokes in films and on tv.

Peter Fryer, The Arab Boarding House, South Shields, 2006

Peter Fryer, The Arab Boarding House, South Shields, 2006

What about the cultural value of the work done by Amber photographers? The photos seem to resonate not just with people living in the North East of England but also with the rest of the country and i think i can also say that they are interesting far beyond the UK borders.

We find that the work resonates enormously with people from other countries. When you go to countries like Spain, France or Germany, you find that people immediately connect with these images. People see that the images depict lives and streets that are not so dissimilar from their own. It’s actually much more the case in Europe than it is in some parts of the UK.

In this country, especially in the cultural world, there is a resistance to document these marginalized worlds. The UK has a few difficulties with documentary. I’m not talking about the audience but about curators and funding bodies. They show some interest in documenting the 1930s and the 1940s up until the 1980s but they don’t seem to be interested in documentaries about the present days.

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker, 1974

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker, 1974

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker Revisited, 2008

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker Revisited, 2008

Konttinen explained to The Guardian why the photo above is her “best shot.”

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker Revisited, 2008

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker Revisited, 2008

Do you think that television is doing a better job at representing the working class then?

No, with TV, we’ve even gone backwards. We are going back to a situation in which the working class is there to provide cheap laughs. But these things come in circles and we need another movement to challenge the current situation.

Peter Fryer, Peaceable Kingdoms, 1992

Peter Fryer, Peaceable Kingdoms, 1992

Julian Germaine, Steel Works, Phileas Fogg Snacks, 1989

Julian Germaine, Steel Works, Phileas Fogg Snacks, 1989

I was reading a letter published in The Guardian this morning. The street photographer was from Birmingham and he explained that he was often stopped in public and private spaces. Security spots him on CCTV and ask him to stop shooting. I haven’t photographed children playing in a public space for many years, and the work of people such as Vivian Maier and Shirley Baker would be impossible these days. It seems to me, from a photographic point of view, that the public space has become privatised, with CCTV everywhere and the lone photographer increasingly unwelcome. Is this something Amber members have noticed as well? Are people still comfortable with being photographed nowadays? Or are they reluctant because of privacy or other concerns?

Yes, when Amber began, street photography was very much a part of what documentary photographers did. But things have changed in a number of ways. Nowadays, people are suspicious that the photographer might be a pedophile for example. Then there is also the issue that part of the public space has been privatized. Almost everyone has a camera phone so, in a way, there is now more street photography than ever. But people are more suspicious than in the past when they see a camera. All of the photographers responded to the challenge in their own way. By negotiating access to people’s life, for example, and by making certain that people were genuinely inviting them into their life. If people were not happy with the photo, the photographer would not use it. This in turn enables the photographer to go further and opens up new areas.

In any case, we’ve lost a significant amount of what is happening in the street. In terms of photography, a lot of questions have been raised as to what is legitimate for a photo to portray.

Amber Films, High Row, 1973

Amber Films, High Row, 1973

I was also curious about Coke to Coke, a series of photographs you worked on together with Peter Fryer. The photos were taken in the 1980s and follow the closure of Derwenthaugh coking plant and the opening of the nearby Metro Centre shopping mall. What was the mood of the people then? Where they angry or sad about the end of an era or optimistic of what the new shopping mail represented?

You can’t generalize of course but i think that when i accompanied Peter to photograph the opening of the Metro Center, we had a sense of people being dazed by it. It was all bright and artificial and protected from the weather. It was like a place to visit. It gave you a sense of the ‘new world.’ And it still does because it is so artificial. People loved it. In the States, it was nothing new but it was the first out of town shopping mall in the UK. There was a fun fair aspect to it, with people looking at the shop as if they were at the fair.

At the time, i had just moved to the Derwenthaugh Valley. Derwenthaugh Coke Works was a vision of Dante’s Inferno at the end of the Valley. One place was closing, another one was opening. It was a symbol of time changing. That’s why we looked at it.

People working at Derwenthaugh Cokeworks were sad but they were also starting to realize that they worked in a cancerogenic atmosphere. Looking back at the ’80s, that’s when people started to think about the environmental impact of fossil fuels. Before that, these issues were not really discussed.

The opening of the Metro Center was a moment in time. The steel making town was closing its steel factory, the miner strikes had failed and Thatcher’s programme of closures was accelerating.

Thanks Graeme!

Bruce Rae, Shipbuilding on the Tyne, 1981

Bruce Rae, Shipbuilding on the Tyne, 1981

Nick Hedges, Fishing Industry, 1981

Nick Hedges, Fishing Industry, 1981

Amber Films, Seacoal (poster), 1985

Amber Films, Seacoal (poster), 1985

Simon Norfolk, Goaf, Dalton Park, 2005

Simon Norfolk, Goaf, Dalton Park, 2005

Amber Films, T Dan Smith, 1987

Amber Films, T Dan Smith, 1987

Amber Films, The Scar, 1997

Amber Films, The Scar, 1997

Amber Films, In Fading Light (still), 1989

Amber Films, In Fading Light (still), 1989

For Ever Amber opens at the Laing Gallery in Newcastle on 27 June and runs until 19 September, bringing together over 150 original photographs and film clips capturing over 40 years of cultural, political and economic shifts in North East England.

‘For Ever Amber’ is a partnership between Amber Film and Photography Collective and Laing Art Gallery, with support from Tyne & Wear Museums and Archive. The exhibition has been supported by Heritage Lottery Fund and Arts Council England.

Image on the homepage: Jimmy Forsyth, Pine Street demolition gang, 1960.