While i was at the LABoral in Gijón for the opening of the exhibition Active Presence (review coming soon on this very screen), i got a chance to check out the art center’s other show: eCLIPSe: [retro]perspective of the music video in 50 steps.

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

The title says it all. 50 milestones in the history of music videos. From Bohemian Rhapsody to Alva Noto’s Uni Acronym. Sitting in an art center to watch video clips that anyone else can open on youtube is exciting and seditious. Seditious because video clips -unlike much of what you can see in museums nowadays- are not only part of mainstream culture, they also wouldn’t think of hiding their mercantile purpose. Exciting because although we might have seen all these videos before, watching them on a big screen forces us to realize that they probably are the most democratic point of entry to video art and more generally to audiovisual culture.

Carlos Navarro (curator of the exhibition in collaboration with Rubin Stein) writes: In our view, it should be included within the visual arts as a separate discipline. In some cases it should even be viewed as avant-garde, though at times it admittedly makes compromises with the commercialism and function a music video must inevitably serve, which is to sell a song, a band or a singer. Surprisingly enough, many of the advances made in the visual mise en scène of art forms enjoying such unquestionable respect as film were originally conceived and rehearsed in music videos. And even the narrative rhythm of the video has set standards for spectators. Likewise, we ought to underscore its inextricable bond with the language of advertising.

The exhibition was a crash course in music video for me. I grew up glued to MTV, got tired of it in the early 1990s and completely lost touch with the discipline in the process. I will therefore be forever grateful to the curators of the show for making me discover this brilliant video:

Justice, Stress, 2008. Directed by Romain Gavras

eCLIPSe charts the evolution of the music video genre. From the early days when musicians themselves were involved in the creation of their own videos (e.g. David Bowie for Ashes to Ashes), to the role that MTV played since its creation in 1981 in making the video the compulsory counterpart of a song, to the ascent of special effects, infographics and digital technologies, to the counter tendency towards amateurism (see Fatboy Slim’s Praise You), to the entrance of online platform for file exchange that opened up windows for exhibiting and viewing videos worldwide, etc.

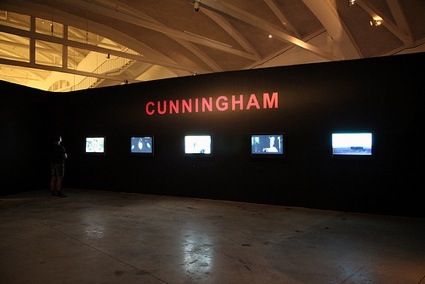

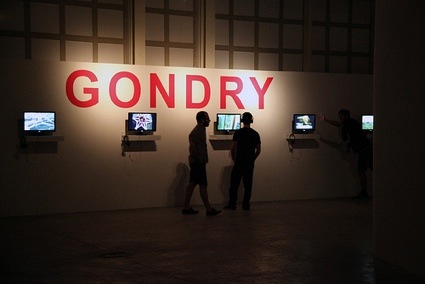

The exhibition also pays homage to two of the most unconventional directors of music videos: Michel Gondry and Chris Cunningham.

Because the exhibition was so unexpected, i wanted to talk to the main curator of the exhibition: audiovisual producer, scriptwriter and director Carlos Navarro.

Hola Carlos! My first curiosity is about Bohemian Rhapsody. You wrote that this is the first video clip ever made. What makes it so special? What did the video of Queen have that other musical videos didn’t? What is so revolutionizing about it?

Although many experts regard Queen’s video as the first self-conscious video made with the purpose of ‘selling’ a song, it is certain that the relationship between music and images comes from afar. At the beginning of the 20th Century, the artistic avant-garde was already playing with these two disciplines. Picabia or Schöenberg, for example, were using that language. Movies by Walt Disney, especially “Fantasia”, were already exploring this relationship. And later, the musical movies of The Beatles can be regarded as authentic music clips. However, the importance of Bohemian Rhapsody lays in the intention expressed by Bruce Gowers and Queen to use images to sell the song, the disk and the band and ultimately in its objective to create a new promotional support.

Queen, Bohemian Rapsody, 1975. Directed Bruce Gowers

I also wondered about objectivity because music is something people are so passionate about. So how did you manage to maintain a sense of objectivity and not let your own taste influence the final selection?

I have to be honest and admit that both I and Rubin Stein, who worked with me on the selection of the works, were often influenced by our personal tastes, not so much in terms of music but for more strictly ‘cinematographic’ reasons.

This doesn’t mean that we haven’t devoted much time to the ‘theoretical’ study of the historical importance of the exhibited works. Nevertheless, what was non-negotiable during the curating process was that our selection had to be unique, different from the ones made in similar exhibitions. Hence, the choice of dedicating two monographs to Michel Gondry and Chris Cunningham. While the historical part arises from the study of the literature on the subject, the decision to add monographs is entirely personal and is founded on concerns that interest me as a narrator and professional of the audiovisual. In a nutshell, in the first phase we behaved like ‘bookworms’ and in the second one as film directors.

Although the selection of works for an exhibition is always debatable, i’d like to claim that “SON TODAS LAS QUE ESTÁN, AUNQUE NO ESTÉN TODAS LAS QUE SON”. I don’t know if you have a similar expression in english, sorry.

That’s a tricky one to translate, but i guess the idea is that ‘All the videos selected belong to the show, but not all the video clips that belong to the show are in the selection.’

David Bowie, Ashes to Ashes, 1980. Directed by David Mallet & David Bowie

Fatboy Slim, Praise You, 1998. Directed by Spike Jonze

Prodigy, Smack My Bitch Up. Directed by Jonas Akerlund

Isn’t there something a bit subversive in bringing popular video clips inside a museum/art space? Why do you think they have their place in a space dedicated to contemporary art?

Introducing an art traditionally considered ‘minor’ in the sacrosanct space of an art gallery was precisely the main reason behind this show – at least for me! The problem of video clips is that we are now used to watching them on a tv or computer screen where they are always subjected to multiple factors that prevent us from giving them our full attention. During their TV broadcasts we could watch them just before an advert for a washing powder, or right after an ad for a bier, or else as part of music program that wouldn’t necessarily differentiate a mainstream clip from an authentic music video artwork. In the end, there’s always been a lot of “noise” around the video clip. Exhibiting video clips in a museum space grants them a formality that forces us to pay further attention, and thus discover all its content. In the case of the monographs, it makes us realize the obsessions and recurrent themes of a creator which, in my view, places the director of music video in the category of visual artist.

Depeche Mode, Enjoy the Silence, 1990. Directed by Anton Corbijn

Finally, have you discovered any new video clip since the show opened that makes you think “damn! this video clip is so fantastic i wish i could add it to the show now!”?

Yes, this is always the case. Even the day after we had closed the selection, new works emerged that i wish i could have added. But an exhibition like this one comes with “auto frustration” otherwise it would have been impossible to close it or put a limit to it: why 50 clips rather than 60? Or even 100?

We would have liked to include a clip of the new trend called “interactive”, such as I´ve seen Footage by Death Grips or some of The Valtari Mystery Film Experiment videos that Sigur Rós have proposed to illustrate their last album. However, the logistical difficulties of doing so were important.

In any case we are very proud of this selection although, of course, we know that it remains open for debate.

Thanks Carlos!

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Image courtesy LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre)

Michael Jackson, Thriller, 1983. Directed by John Landis

Alva Noto, Uni Acronym, 2011. Directed by Carsten Nicolai

The exhibition closed a few days ago but it will travel with Fundación Telefónica to venues in Latin America, i’ll keep you posted about the dates and locations via twitter and the blog’s facebook page. In the meantime, you can find more information in the press kit.