Previously: Permanent Error.

If you’re under 14 and eager to visit the exhibition Disquieting Images at the Triennale in Milan, then i’m afraid you’ll have to convince your parents to accompany you.

Sahla. Severely injured Iraqis live and get treated in the Kaser Jaddah hotel in Amman as part of an MSF run operation. Jordan 2008 © Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos

Sahla. Severely injured Iraqis live and get treated in the Kaser Jaddah hotel in Amman as part of an MSF run operation. Jordan 2008 © Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos

Diane Arbus Russian Midget Friends in a Living Room on 100th Street, N.Y.C 1963

Diane Arbus Russian Midget Friends in a Living Room on 100th Street, N.Y.C 1963

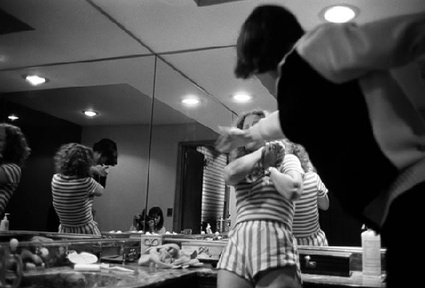

Nan Goldin, Skinhead with Child, London, 1978

Nan Goldin, Skinhead with Child, London, 1978

The show is indeed disturbing. Not so much for the images but for the issues they uncover: domestic violence, decaying corpses, mass graves for cattle, post-war trauma, pollution, nonconformist sexual practices, etc. I’m almost ashamed to admit how much i enjoyed the show. It was extremely moving even if it made me feel sometimes as if i were a voyeur and a vulture.

Curators Germano Celant and Melissa Harris have hung on the white walls of the Triennale 260 pictures from 24 contemporary photographers. Each of these images follow the footsteps of the photos which surfaced from Vietnam in the ’60s and ’70s and were so shocking that they played a crucial role in changing public opinion about the war.

Images that emerge from conflicts are so powerful that in the early ’90s, at the start of the Gulf War, the U.S. government has restricted the photographing or filming of dead soldiers or their caskets and its subsequent broadcast in the U.S.

Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Philip Jones Griffiths knows about military censorship. Following the publication of Vietnam Inc. in 1971, he was banned from re-entering Vietnam. Until 1980 when the photographer traveled back there to document the effect of the U.S.’s chemical warfare. Griffiths spent several months in the country to meet some of Vietnam’s estimated 1 million victims of Agent Orange, one of the herbicides and defoliants used by the U.S. military to defoliate forested and rural land, depriving guerrillas of cover and forcing peasants to leave the countryside.

“Spending time with the affected children is never easy – twenty year-olds living in ten year-old bodies. Some howling like animals, some giggling hysterically while others search with catatonic stares for meaning in the heavens… Giving birth becomes a game of roulette”. –Philip Jones Griffiths.

Tran Ngoc, photographed in Vietnam in 1998, suffers from Spina Bifida and is mentally retarded. His father lived in an area sprayed with Agent Orange during the war. Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Tran Ngoc, photographed in Vietnam in 1998, suffers from Spina Bifida and is mentally retarded. His father lived in an area sprayed with Agent Orange during the war. Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Philip Jones Griffiths, from the series Agent Orange. © Philip Jones Griffiths/Magnum Photos

Nina Berman‘s wedding photo of wounded Iraq War veteran Ty Ziegel and his bride, Renee Kline, has become one of the most iconic images of contemporary warfare. The young US marine suffered horrific burns after a suicide bomber blew himself up by his truck in Iraq. After months in hospital, he went back home and married his high school sweetheart. A few months later, the couple divorced. The portrait is part of a series that follows Ziegel’s recovery, homecoming and wedding day.

Tyler and Renee, 2006 © Nina Berman/NOOR/Galerie Jacques Cerami

Tyler and Renee, 2006 © Nina Berman/NOOR/Galerie Jacques Cerami

Also present at the Triennale is her Purple Hearts series which portrays American soldiers who were submitted to heavy surgery after having been wounded in Iraq.

Ty and Flags, 2006 © Nina Berman/NOOR/Galerie Jacques Cerami

Ty and Flags, 2006 © Nina Berman/NOOR/Galerie Jacques Cerami

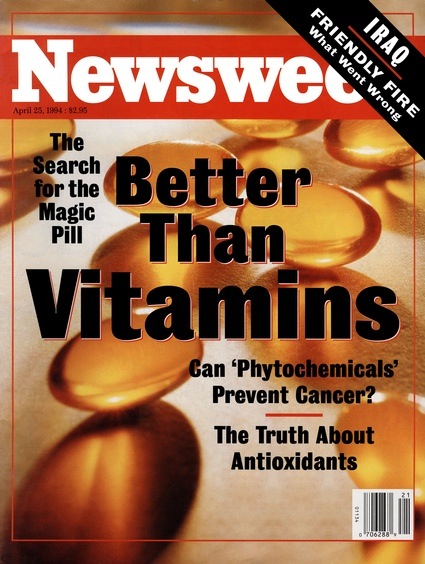

As Alfredo Jaar‘s Untitled (Newsweek), 1994 demonstrates, images documenting horrifying events do not necessarily get to the front page. A painful contrast to the images that James Nachtwey took in Rwanda (see b&w picture below), Untitled (Newsweek), 1994 brings side by side the covers of Newsweek published during the unfolding of the Rwandan genocide and the historical facts pertaining to the genocide. Yet, for months, the genocide will be absent from the covers of the American news magazine. The focus is instead on the deaths of Kurt Cobain, vitamin pills, the trial of O.J. Simpson, etc.

Alfredo Jaar, Untitled (Newsweek), 1994

Alfredo Jaar, Untitled (Newsweek), 1994

By the time the magazine finally devoted a headline to Rwanda, in August 1994, more than one million people had been killed.

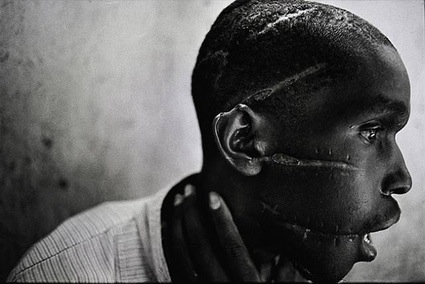

James Nachtwey, Rwanda, 1994

James Nachtwey, Rwanda, 1994

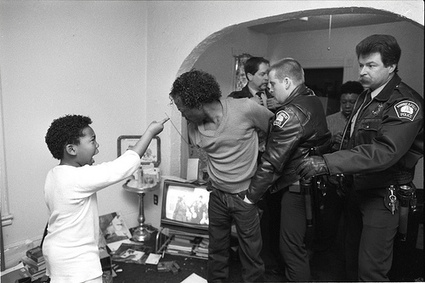

“The boy is saying to his father, ‘I hate you for hitting my mother, and I hope you never come back to this house.’ Nobody, even the parents who signed a release for this picture, realized how powerful it was going to be until they saw it in the magazine and they flipped out.” –Donna Ferrato.

The Arrest, 1987 © Donna Ferrato

The Arrest, 1987 © Donna Ferrato

Donna Ferrato‘s Living with the Enemy documents domestic violence in the early ’80s. At the time, women abused by their partner didn’t talk about their suffering. They didn’t call the police either, police officers seldom intervened anyway. It is partly due to Ferrata’s series that the issue of domestic violence finally gained significant attention in the USA .

Donna Ferrato, Living With The Enemy, Copyright 2009 Donna Ferrato/AbuseAware.com

Donna Ferrato, Living With The Enemy, Copyright 2009 Donna Ferrato/AbuseAware.com

Donna Ferrato, Living With The Enemy, 1982. Lisa and Garth fighting over a cocaine pipe. Copyright 2009 Donna Ferrato/AbuseAware.com

Donna Ferrato, Living With The Enemy, 1982. Lisa and Garth fighting over a cocaine pipe. Copyright 2009 Donna Ferrato/AbuseAware.com

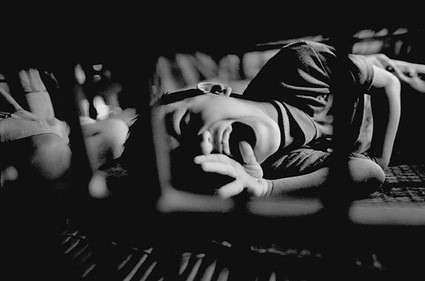

With Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue, Eugene Richards chronicles the usage and effects of hard-core drugs in North East USA through the 1980’s and early 1990’s.

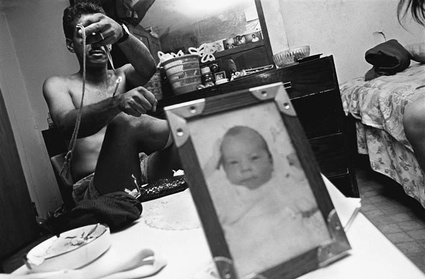

Eugene Richards, from the series Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue

Eugene Richards, from the series Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue

Richard Misrach‘s photographs of The Pit follow the process of decomposition at three mass graves for dead animals in the Nevada desert. The reason for the sudden death of the horses, sheep and cattle may be related to a nearby nuclear test site. The highly aesthetic images are so distressing that they resulted in an investigation by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Richard Misrach, Dead Animals #1, 1987

Richard Misrach, Dead Animals #1, 1987

Images on La Repubblica and Il Corriere.

Disquieting Images, an exhibition co-curated by Germano Celant and Melissa Harris, remains open at the Triennale in Milan through 9th January 2011.