Previously: Art, bricks, domestic dust.

Dirt: The filthy reality of everyday life, a spectacular exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London, travels across centuries and continents to explore and expose our confused relationship with dirt.

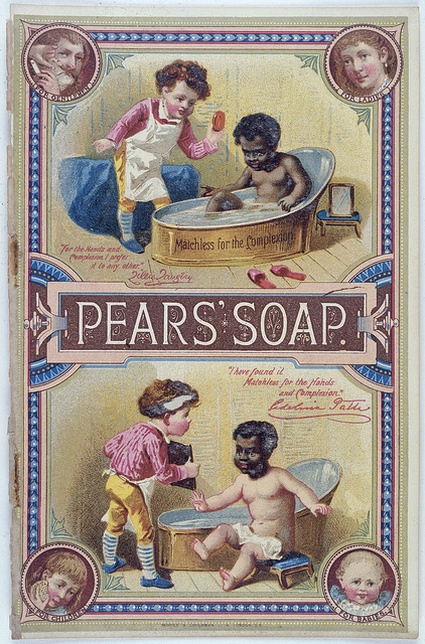

Advertisement for Pears’ Soap. Caption reads, “Matchless for the complexion…” Illustration of ‘before and after’ use of soap by black child in the bath. Showing soap washes off his dark complexion. Date of Publication188-? Wellcome Library, London

Advertisement for Pears’ Soap. Caption reads, “Matchless for the complexion…” Illustration of ‘before and after’ use of soap by black child in the bath. Showing soap washes off his dark complexion. Date of Publication188-? Wellcome Library, London

Our society appears to abhor dirt. Until you look closer… A can containing (or not) Piero Manzoni’s shit was sold for EUR124,000 at Sotheby’s in 2007. The same person who wouldn’t leave the house without disinfecting wipes in the handbag would find the presence of dirt in certain, precise circumstances perfectly acceptable. The dust covering a bottle of wine in the cellar is one example. Or that bit of soil worn by organic carrots like a badge of honour.

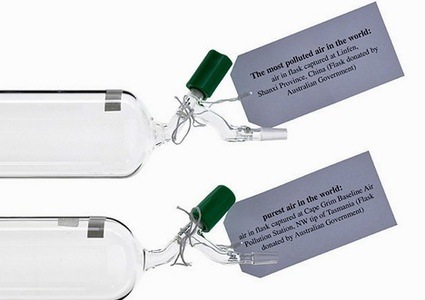

No dirt, however, is most treacherous than the one that is invisible to the human eye. Angela Palmer‘s project Breathing In illustrates how identical the world’s worst and least polluted air appear once they are captured inside glass bottles. The artist traveled to Linfen, China, a city with the most polluted air on Earth, and to the place with the purest air and water on Earth, Cape Grim in Tasmania (videos.)

Images Angela Palmer and the Wellcome Collection

Images Angela Palmer and the Wellcome Collection

The Dirt exhibition examines attitudes towards dirt and cleanliness through six moments and locations: a home in 17th-century Delft in Holland, a street in Victorian London, the Lister Ward at Glasgow Royal Infirmary hospital in the 1860s which was associated with Joseph Lister’s pioneering work in reducing infection rates, the Hygiene-Museum in Dresden in the early 20th century, the a community of manual scavengers who clear the waste from New Delhi’s public latrines in present day and Fresh Kills, a New York landfill site which is in the process of being turned into a model for state-of-the-art environmental preservation.

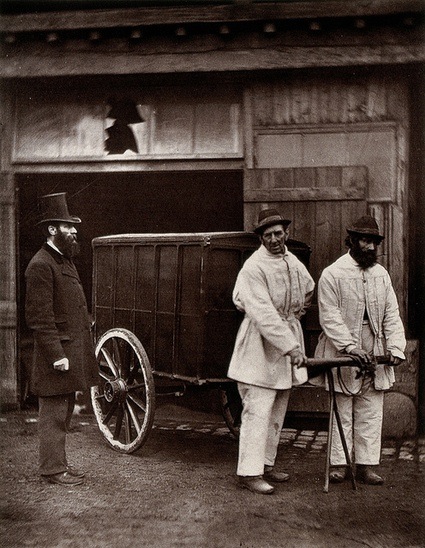

Public disinfectors from the Parish of St. George, Hanover Square, London: two men wearing white overalls are shown pulling a covered hand-cart containing a mobile disinfection unit, observed by Mr. Dickson, Inspector of Nuisances. Woodburytype after a photograph by J. Thomson, 1877. Wellcome Library, London

Public disinfectors from the Parish of St. George, Hanover Square, London: two men wearing white overalls are shown pulling a covered hand-cart containing a mobile disinfection unit, observed by Mr. Dickson, Inspector of Nuisances. Woodburytype after a photograph by J. Thomson, 1877. Wellcome Library, London

As usual, the Wellcome exhibition is bringing side by side historical artefacts (such as the earliest sketches of bacteria, racist adverts for soaps, John Snow’s ‘ghost map’ of cholera, Joseph Lister’s scientific paraphernalia) and a wide range of contemporary art. Instead of a clean cut review i’m going to throw here a few images from the show with comments:

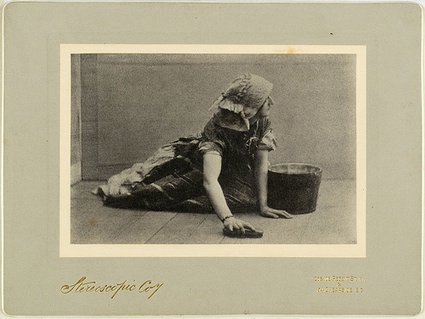

In 1854, Hannah Cullwick met Arthur Munby. Hannah was maid. Arthur was an upper class solicitor who had a secret obsession with working women. The two of them entered a loving ‘slave-massa’ relationship. She would arrange to visit him “in my dirt”, showing the results of a full day of cleaning and other domestic work. She had a particular interest in boots, cleaning hundreds each year, sometimes by licking them. She once told Munby she could tell where her “Massa” had been by how his boots tasted. Against all conventions of the times, Arthur and Hannah got married.

Hannah Cullwick scrubbing the floor, 1857. Credit: : Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

Hannah Cullwick scrubbing the floor, 1857. Credit: : Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

When Joseph Lister, a pioneer of antiseptic surgery, discovered that carbolic acid (which we now call phenol) was being used to extinguish unpleasant smells in the sewers of nearby Carlisle, he decided to apply the same principle in the operating theatre by using carbolic acid, in spray form, to eradicate bacteria and minimise the risk of infection.

Carbolic spray, 1878 Credit: Hunterian Museum

Carbolic spray, 1878 Credit: Hunterian Museum

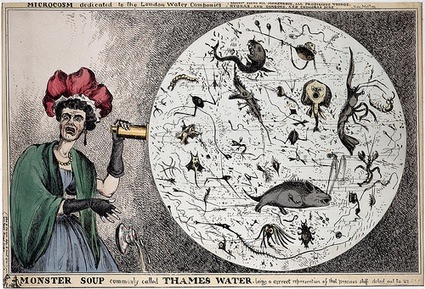

The Thames remained relatively clean until 1815, when – in an effort to relieve the city’s overflowing cesspools – house drains were connected to sewers that had previously functioned principally to carry off rainwater. Inadequate infrastructure, the impact of overcrowded slums, poor workmanship and the growing popularity of the flush toilet, soon turned the river into a giant stinking sewer.

William Heath, Monster Soup, commonly called Thames Water’, 1828. Wellcome Library, London

William Heath, Monster Soup, commonly called Thames Water’, 1828. Wellcome Library, London

A sinister and claustrophobia-inducing ‘epidemic ambulance’, with only a tiny window for the afflicted to look out.

Epidemic ambulance, Medicinsk Museion Copenhagen (photo)

Epidemic ambulance, Medicinsk Museion Copenhagen (photo)

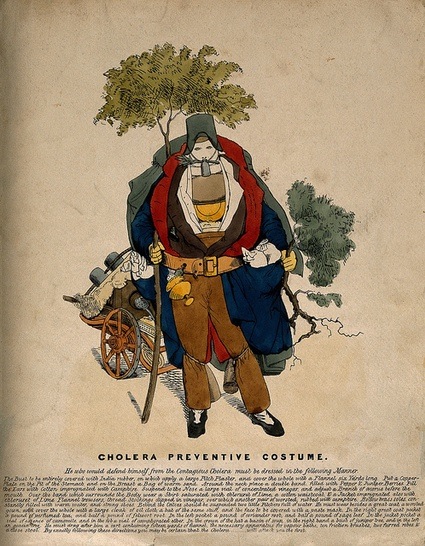

A figure dressed in a cholera safety suit. Coloured etching. Wellcome Collection, London

A figure dressed in a cholera safety suit. Coloured etching. Wellcome Collection, London

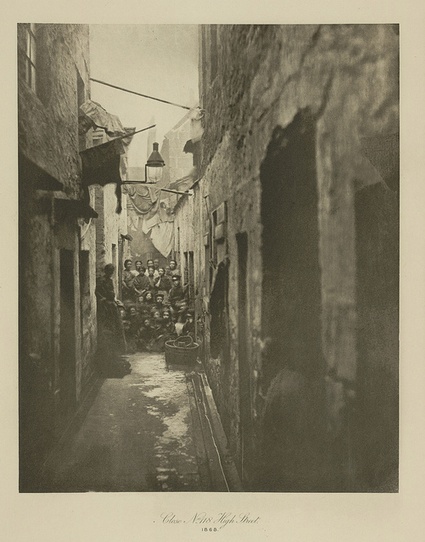

A fashion for ‘slum tourism’ where philanthropy mingled with voyeurism saw hordes of middle class Victorians visit slums.

Close, No.80 High Street, children loiter in an alley close to an overflowing gutter, 1868. Thomas Annan Credit: British Library Board L.R.404.g.8

Close, No.80 High Street, children loiter in an alley close to an overflowing gutter, 1868. Thomas Annan Credit: British Library Board L.R.404.g.8

Santiago Sierra’s odourless, dark monoliths of human excrement. The material was originally collected and shaped in New Delhi and Jaipur by the people of Sulabh International, lower caste scavengers who by birth, have to collect human waste.

Santiago Sierra, Anthropmetric modules

Santiago Sierra, Anthropmetric modules

The work is strangely not as powerful as Senthil Kumaran‘s photos showing the daily work of manual scavengers. Across India nearly 1.3 million of these people are employed to remove human excreta from sewers and septic tanks. They don’t wear protective gear and use tin plates, small brooms and baskets to carry the waste to dumping grounds. The practice persists despite its official ban.

Senthil Kumaran, from the Manual Scavengers series, India, 2007. A group of scavengers, including a 14-year-old boy, fully engaged with their every day usual work of cleaning the human excreta from the septic tank of public toilets. Photo: Senthil Kumaran/Trikaya Photo

Senthil Kumaran, from the Manual Scavengers series, India, 2007. A group of scavengers, including a 14-year-old boy, fully engaged with their every day usual work of cleaning the human excreta from the septic tank of public toilets. Photo: Senthil Kumaran/Trikaya Photo

By 1933, the Hygiene-Museum’s innovative communication methods and ideas about popular health education had been co-opted into the service of the Nazi party. ‘Hygiene’ now encompassed the so-called ‘science of racial hygiene’, which taught that ‘impure’ genes must be eradicated to create a physically and intellectually superior race. Wider Nazi propaganda characterised foreigners as unclean or personified them as germs.

Aerial photograph showing the Hygiene Museum and pavilions at the International Hygiene Exposition in 1931. Credit: Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden

Aerial photograph showing the Hygiene Museum and pavilions at the International Hygiene Exposition in 1931. Credit: Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden

Jews being forced to scrub the pavements of Vienna. Photograph, 1 March 1938

Jews being forced to scrub the pavements of Vienna. Photograph, 1 March 1938

A section of the exhibition is dedicated to Fresh Kills. The site opened as a landfill in 1948 and received its last barge of waste in March 2001. Scheduled to close in 2001 authorities had to briefly reopen it following the World Trade Center tragedy in September 2001.

Last barge of garbage to Fresh Kills, March 22nd 2001. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Last barge of garbage to Fresh Kills, March 22nd 2001. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Front loaders on garbage mound at Fresh Kills. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Front loaders on garbage mound at Fresh Kills. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Garbage mound at Fresh Kills. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Garbage mound at Fresh Kills. Credit: Courtesy of the City of New York

Landscape architects James Corner Field Operations lead the team redeveloping the 2000 acre site. The project involves the reclamation of former salt marshes, meadows and woodlands, and the reappropriation of some 150 million tons of waste.

Aerial View of Fresh Kills Park Credit: James Corner Field Operations / Courtesy of the City of New York

Aerial View of Fresh Kills Park Credit: James Corner Field Operations / Courtesy of the City of New York

James Croak’s Window is cast from street-sweeper’s dirt.

James Croak, Window #1. Wellcome Library, London, 1991

James Croak, Window #1. Wellcome Library, London, 1991

Dirt, Wellcome Collection

Dirt, Wellcome Collection

Dirt: The filthy reality of everyday life is on view at the Wellcome Collection until August 31, 2011. More stories about the exhibition soon.

Related stories: The Race and Art, bricks, domestic dust.