Previously: Design and Violence. Part 1: ambiguous violence.

DESIGN AND VIOLENCE at Science Gallery Dublin (trailer)

Violence, in particular, permeates everything around us, as one of the central organising principles of human affairs. One of the definitions of a modern state is that it reserves the right to violence for itself, while excluding it from others it terms dissidents or criminals, wrote Ralph Borland in an essay about DESIGN AND VIOLENCE, the exhibition he co-curated for the Science Gallery Dublin.

DESIGN AND VIOLENCE, a collaboration between the MOMA in New York and the Dublin space, displays objects and systems that are imbued with violence. Sometimes this violence is deliberate, other times it is the unfortunate and unintended consequence of a particular idea or design. Some of these objects and systems have been part of our society for far too long. Others have emerged only recently. What these pieces have in common is that they demonstrates that violence is everywhere around us and design has a role to play in it. It can fight violence but it can also normalize it, hide it from our consciousness and even heighten its brutality.

There are dozens of artifacts in the show. The ones that i found most powerful shouldn’t actually concern me at all. I’m simply not the target.

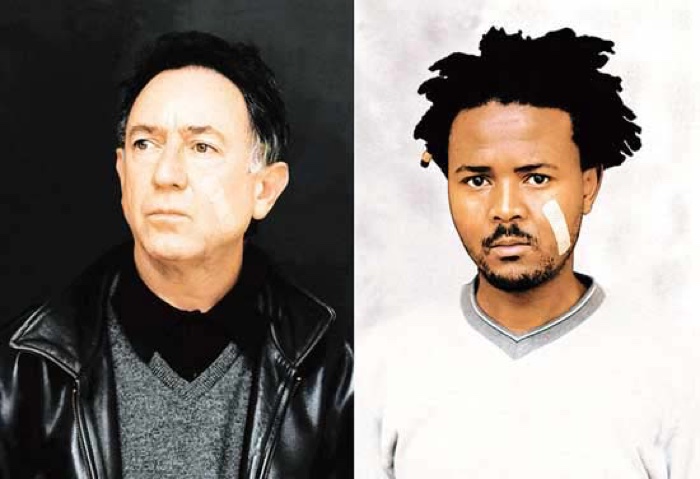

Thembinkosi Goniwe, Dignities, 2000

I was particularly moved by South African artist Thembinkosi Goniwe’s diptych Dignities which shows a portrait of the artist alongside his professor of painting. Both men sport a ‘flesh-coloured’ plaster on their cheeks. While the white man’s epidermal misfortune passes unnoticed, the skin of the black artist seems to be partly erased by the plaster, as if was an error that had to be amended.

The unassuming plaster speaks about ordinary violence, the one that caters for some but discriminates and disregards others, the one that hides prejudice and racial inequality in plain sight.

Compound Security Systems, Mosquito, 2005. At Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin

I was equally taken aback by the infamous Mosquito. This ‘anti-loitering device’ emits an unpleasantly high-pitched sound that only young people can hear, as adults’ capacity to hear high frequencies deteriorates with age. I remember reading about it a while ago and thinking it was amusing. Not so much now. The young (and brilliant) guide who gave me a tour of the show told me how present the sound is in his every day life. Because i’ve long been immune to it, i can, unlike him and countless others whose sole crime is to be young, walk around the city without ever being harassed by high-pitch intolerance.

The manufacturers of the Mosquito promote it as follows: “Every day we receive calls from people wanting to buy a Mosquito Anti-loitering Device. People like you who are fed up with groups of kids damaging their property, hanging around in rowdy groups, smoking and drinking, playing music and generally preventing you from enjoying your home or business… The Mosquito device is the only product on the market that has the teeth to bite back at these kids”.

In 2009, the Children’s Rights Alliance issued a note that stated: The Children’s Rights Alliance, as a coalition of over 90 NGOs working with and for children in Ireland, wants to firmly raise its voice against the continued use of the Mosquito Teen Deterrent, which not only violates the fundamental rights of children and young people but also fosters negative stereotypes towards them.

The Repeal Project, Repeal Jumper, 2016. At Science Gallery Dublin

I might not be black nor a teenager but hey! i’m a woman and gender-bias is still very much alive in design (if you think design is just design and is devoid of any cultural, gender, racial or other prejudice, check out the excellent book The Politics of Design. A (Not So) Global Manual for Visual Communication by Ruben Pater.) Many objects and practices reveal the need for women to defer to a ‘higher’ (usually male) authority in order to know what to do with their body. How to cover/uncover it, for example. Or what the limits and standards of their reproductive rights are.

A black jumper bearing the word ‘REPEAL’ is presented in the gallery next to a book opened on the page of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution of Ireland. The text states that abortion is illegal in the country. The juxtaposition of the jumper and the book makes the enigmatic word on the garment clearer: what needs to be repealed is the ban on abortion. The Repeal Project, set up by activist Anna Cosgrave, aims to ‘give a voice to a hidden problem’ and help raise money for the Abortion Rights Campaign. Lucky you if you managed to get one of these jumpers because they tend to sell out VERY quickly in the country.

International gathering in Dublin outside the Department of the Taoiseach in 2015, with suitcases to signify women obliged to travel to the UK for a safe and legal abortion. Pictured is Maureen Gombakomba. Photo: Nick Bradshaw

Nearby a simple black suitcase emblematizes the Irish women who have to travel abroad to have access to abortion care. Every day, up to 12 of them pack their bags and take the plane or the boat to have access to the procedure.

Carlotta Werner and Johanna Sunder-Plassmann, Hacked Protest Objects. At Science Gallery Dublin

Protests in Hamburg. Image Daniel Müller

Carlotta Werner and Johanna Sunder-Plassmann, Hacked Protest Objects. At Science Gallery Dublin

The suitcase is part of a group of mundane objects that have been re-appropriated by protesters around the world and given an extra layer of meaning in the process.

The cleaning sprays are actually filled with milk or other liquids that soothe the effect of teargas on the eyes. During the Hamburg demonstrations, the humble toilet brush came to symbolize public anger after a video was shot that showed police in riot gear confiscating the bathroom utensil from a man who had been stopped in the street.

Patrick Clair, Stuxnet: Anatomy of a Computer Virus, 2011

A group of works reminded me that violent design can be impalpable and devious.

Patrick Clair’s motion infographic Stuxnet: Anatomy of a Computer Virus visualizes in a fast and efficient fashion the inner workings and impact of Stuxnet, a malware that changed global military strategy in the 21st century. This malicious computer worm delivered via a USB drive was designed to disrupt programming instructions that control assembly lines and industrial plants. Regarded as the first weapon made entirely from code, Stuxnet has been linked to a policy of covert warfare against Iran’s nuclear armament that might have been led by the U.S. and Israel.

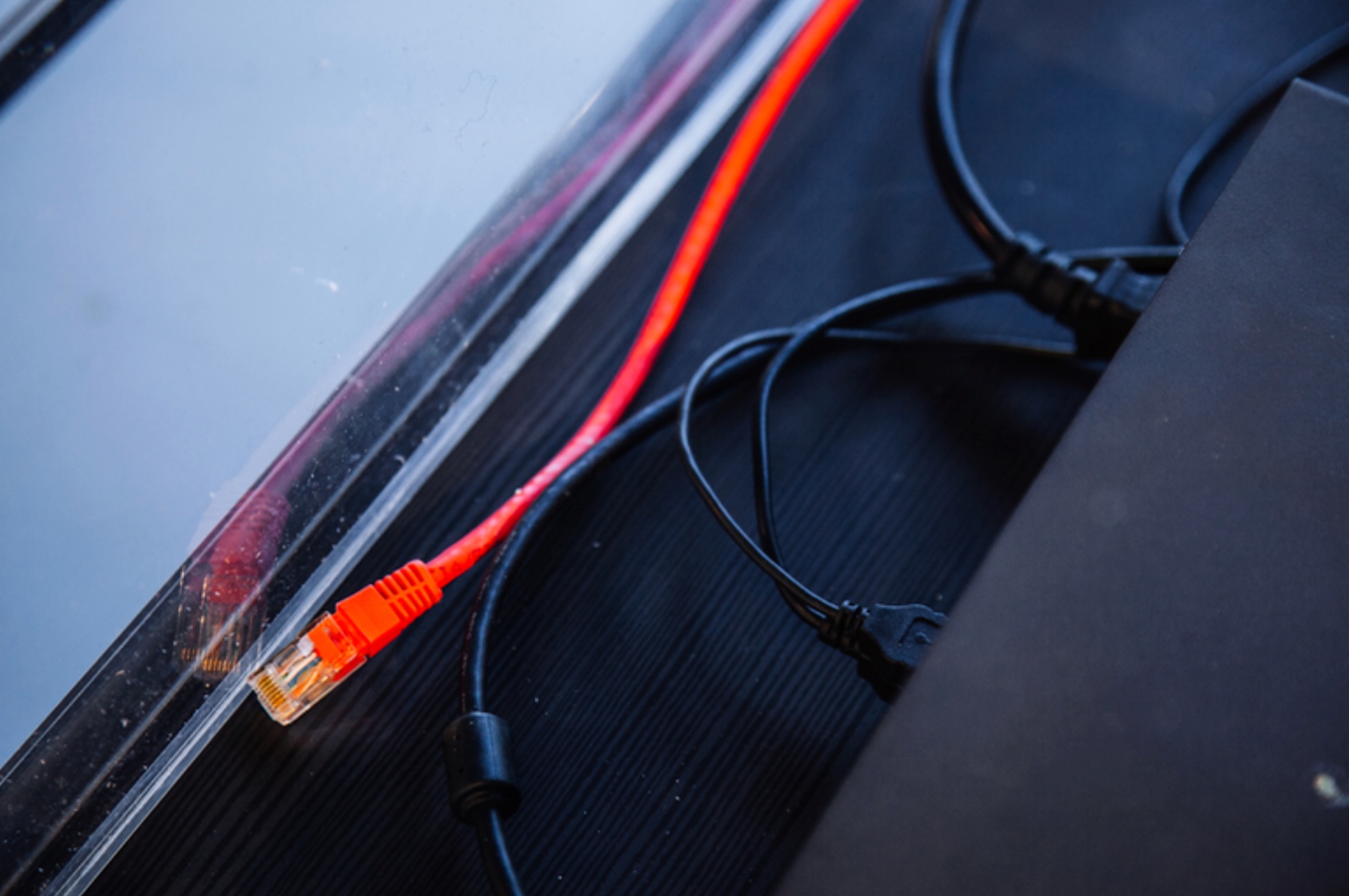

Julian Oliver, Solitary Confinement, 2013. At Science Gallery Dublin

Julian Oliver, Solitary Confinement, 2013. At Science Gallery Dublin

Julian Oliver’s Solitary Confinement exposes the tangible and physical dimension of cyberwarfare but also our supine ignorance that none of us is immune to its attacks. His “non-interactive installation” shows a computer quarantined within a glass vitrine that has been deliberately infected with the Stuxnet Virus. It sits in a vitrine, powered on, with one end of a red ethernet network cable that is connected to the gallery network laying unplugged near the port on the PC.

The vitrine cover is screwed down and the cable cannot be accessed.

Here the visible state of disconnection evokes both a volatile, techno-poltiical tension and an aura of anxiety; Stuxnet, one of the world’s most dangerous works of software, needs only a connection to the Internet to continue its destructive quest.

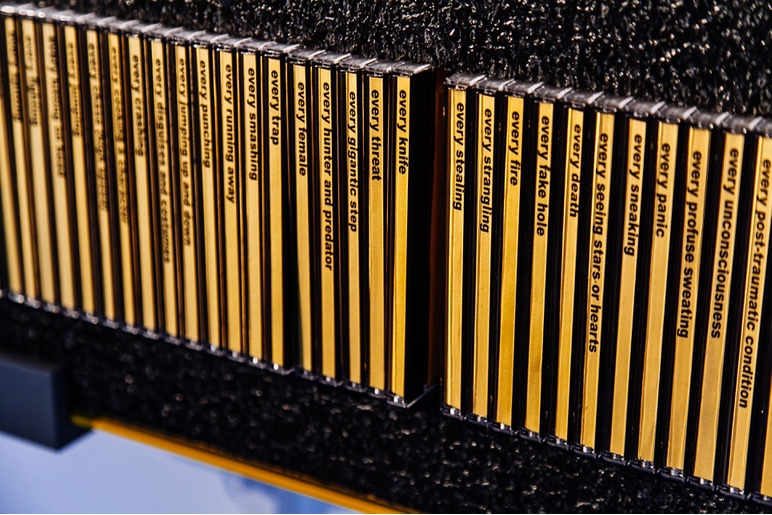

Kevin & Jennifer McCoy, Every Anvil, 2002. At Science Gallery Dublin

Kevin & Jennifer McCoy, Every Anvil, 2002. At Science Gallery Dublin

Finally, the first thing that the words ‘design’ and ‘violence’ evoke might not be some good old Warner Bros. cartoons but it wouldn’t be Science Gallery Dublin if there wasn’t a bit of humour and levity among all the informative and thought-provoking artifacts. Artists Kevin & Jennifer McCoy were showing a collection of video CDs bearing titles such as “every beg and plead”, “every hitting on head”, “every post-traumatic condition”, “every pounding”, “every spitting”, “every scream and yell”, “every flattened character”, “every anvil,” etc. The material for each CD was taken from one hundred episodes of Looney Tunes cartoons. Each scene found in the animated movie displaying a particular form violence or physical extremity was assigned to an individual CD. When you start watching the snippets of cartoons, it all seems quite comical (and also a bit passé.) After a few moments however, when you’ve seen one character after another being squashed by an anvil, you end up feeling that the American comedy reveled in viciousness and all the kids around the world grew thinking this was funny.

More images, videos and things i liked in the DESIGN AND VIOLENCE exhibition. They didn’t quite fit to the theme of this post but i couldn’t resist sharing them:

Flechettes. At Science Gallery Dublin

Darts from a flechette shell embedded in a wall in Gaza, 2009. Photograph: Ben Curtis/AP, via The Guardian

Small metal darts, known as flechettes, have been used in various forms since World War I. They are effective at penetrating dense vegetation and targeting infantry. Their use is controversial because their lack of precision means that they can maim and kill children, women and soldiers without discrimination. Which doesn’t prevent Israel to use them in Palestine and Lebanon.

They actually also bear a striking similarity to the nail bombs often used by terrorists.

The Propeller Group, AK-47 vs M16, 2015. At Science Gallery Dublin

The Propeller Group, AK-47 vs M16, 2015. At Science Gallery Dublin

The Propeller Group, AK-47 vs M16, 2015. At Science Gallery Dublin

AK-47 vs M16: two assault riffles fired at each other inside a block of ballistic gelatin.

Mikhail Kalashnikov, AK-47, 1947. At Science Gallery Dublin

The icon of violent design! High school students in Russia are required to take classes in military education. To pass the course students have to be able to take apart and reassemble a Kalashnikov rifle in a few seconds.

Factory Furniture, Camden Bench, 2012. At Science Gallery Dublin

Ruben Pater, Drone Survival Guide. At Science Gallery Dublin

DESIGN AND VIOLENCE: Conversation with the curators Paola Antonelli, Ralph Borland, Jamer Hunt and Lynn Scarff

Agence France-Presse, White Torture. At Science Gallery Dublin

Elaine Hoey, The Weight of Water, 2016. At Science Gallery Dublin

Forensic Architecture, Bomb Cloud Atlas, 2016. At Science Gallery Dublin

Forensic Architecture, Bomb Cloud Atlas, 2016. At Science Gallery Dublin

View of the exhibition space at Science Gallery Dublin

The show is based on an online curatorial experiment originally hosted by the MOMA in New York and led by Paola Antonelli and Jamer Hunt. The Dublin team, namely Ralph Borland, Lynn Scarff and Ian Brunswick, adapted it to the gallery space by picking dozens of artifacts from the original online collection and adding new artifacts to it.

DESIGN AND VIOLENCE remains open at Science Gallery Dublin until 22 January 2017.

Previously: Design and Violence. Part 1: ambiguous violence.