Gregory Green, Untitled (2 Remote-Controlled Gas Bombs), 2005. At Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin

Zip Gun, at Science Gallery Dublin

Sako, Green Bullets at Science Gallery Dublin

One of the things i’ve learnt from the Design and Violence exhibition at Science Gallery in Dublin is that violence can be found almost everywhere. It can be as sophisticated as the result of genetic manipulation, or as simple as a sweatshirt with a few letters printed on it. It can be ordered online for a couple of euros or it can be a lavishly designed work of architecture. It can be recognizable by everyone or it can be so subtle and elusive that it remains undetected by most people.

DESIGN AND VIOLENCE, a show that explores the pervasiveness of violence in society, started as an online experiment at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and is now taking a life of its own at Science Gallery Dublin. The exhibition explores the collision of design and violence through dozens of artworks, props, artifacts and videos. I spent a whole afternoon there and came back the day after to spend more time with the few works i had not properly examined on my first visit. Every single piece exhibited has a fascinating story to tell and can also act as the catalyst for an intense discussion (both the fantastic guide at the Science Gallery and i were intellectually exhausted after my tour of the show!)

I’ll start my review of DESIGN AND VIOLENCE with a post dedicated to works that kept my brain busy long after i had left Dublin. What they all have in common is that their design and violence are ambiguous. They start with what looks like a laudable impulse, only in the most ruthless context possible: rice that feeds hungry populations but pollutes the environment with pesticides, a brutal weapon that causes pain but not so much pain that it will kill, animal welfare in slaughterhouses, and other oxymoron.

Sako, Green Bullets at Science Gallery Dublin

Perhaps the artifacts that illustrates the point with the most simplicity and clarity are the environmentally-friendly bullets. A Finnish firearm manufacturer uses copper instead of lead to ensure that the bullets will kill you but without contaminating the food chain or water supply. Is this cynical or praiseworthy?

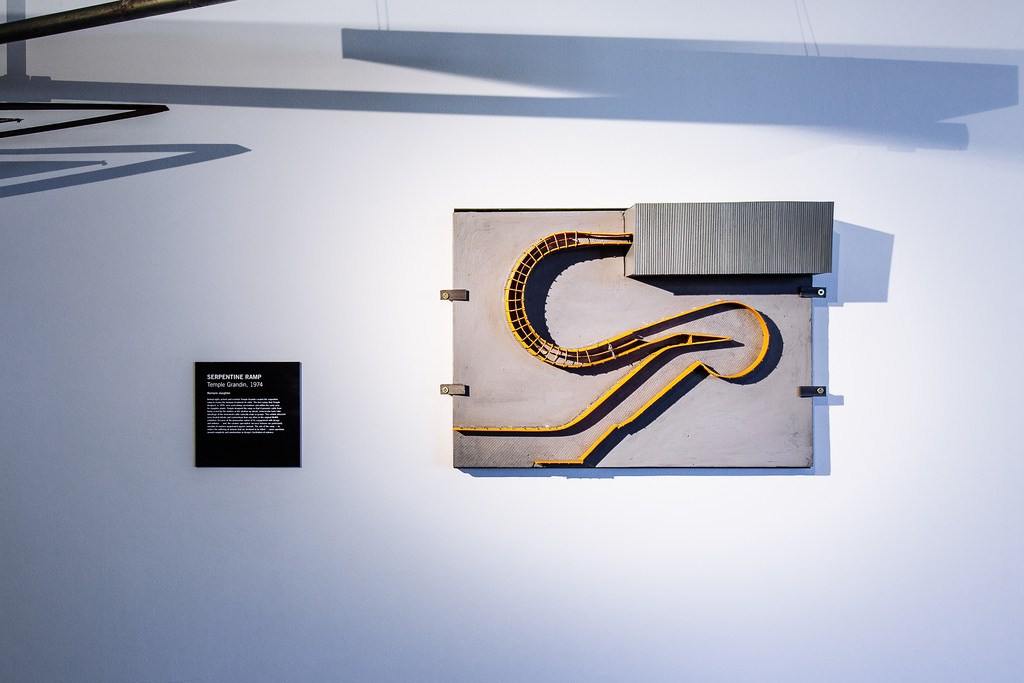

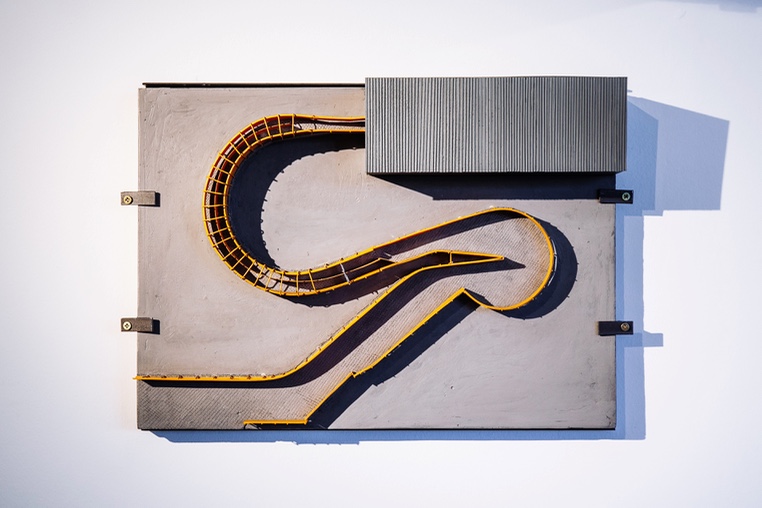

Temple Grandin, Serpentine Ramp, 1974. At Science Gallery Dublin

Temple Grandin, Serpentine Ramp, 1974. At Science Gallery Dublin

Temple Grandin, Design of Curved Cattle Corrals, Yards, Races, and Chutes

Then the example of design i can’t make up my mind about is the one that guarantees that animals are killed as humanely as possible before they are turned into fast food products. Whatever humanely means in this context…

Temple Grandin is an animal rights activist and a scientist. She is opposed to violence against animals but believes that since people are not going to stop eating meat any time soon, they might as well ensure that animals suffer as little as possible. Having observed and studied animal behaviour, Grandin corrected the design of slaughterhouses to ensure that cattle don’t panic and make the slaughter business even more awful.

Her designs include a serpentine ramp that leads cows into the stunning chute. Its serpentine shape is based on cattle’s natural circling behaviour and tendency to want to go back where they came from. It also prevents the animals from being stressed by the sight of workers up ahead.

Is Grandin’s design ‘humane’ or is it complicit in the mass murder of animals? Is she championing animal welfare reform in the cattle industry from the inside out or is she giving the industry and the meat eaters an excuse to continue killing pigs, cows, chicken and sheep without much concerns for the rights of non human animals?

International Rice Reasearch Insitute, IR8. IR8 pictured next to its parents, “Peta,” a tall, vigorous variety from Indonesia, and the Taiwanese dwarf variety “DGWG.” 2009. Image IRRI

First produced in 1966 by the International Rice Research Institute, the IR8, or ‘miracle rice’, was genetically modified to increase its yield and respond to the food crisis. However, its cultivation necessitates the use of high amounts of nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, and intensive irrigation. The social and ecological effects of the Green Revolution of the first half of the 20th century are high and their extent has yet to be fully grasped.

Defense Distributed, Liberator, 2013. At Science Gallery Dublin

The Liberator is not the most efficient weapon but that might not even be the point. What this 3D-printed gun really excels at is forcing people to question the dazzling promises of technology. 3D printing used to be this democratizing technology that would enable us to innovate and manufacture easily, cheaply, from the comfort of our own home. And 3D printing is still a wonderfully liberating technology. But it is also one that comes with more plastic, more harmful air emissions, more patents that stifle independent innovation, etc. As well as print as you want weapons.

Invoking civil liberties -in particular the right to free speech- and challenging our acceptance of information censorship, Defense Distributed created a polymer .380 caliber gun 3D printed in 16 pieces, now known as ‘The Liberator.’ The weapon’s files were made available online so that anyone with access to a 3D printer could fabricate a firearm. Or twelve. Although government authorities in the United States (a country that certainly doesn’t need more guns) shut down its distribution almost immediately, the code for the Liberator has already been downloaded more than 100,000 times.

One of the reasons put forward for banning The Liberator (or rather the computer code behind its fabrication) is that it doesn’t set off a metal detector. “Security checkpoints, background checks, and gun regulations will do little good if criminals can print plastic firearms at home and bring those firearms through metal detectors with no one the wiser.”

Defense Distributed is currently involved in a court case arguing for the code’s distribution as an example of free speech.

Michael Madsen, Halden Prison (designed by Erik Møllet and HLM Architects), Halden, Norway

Michael Madsen, Halden Prison (designed by Erik Møllet and HLM Architects), Halden, Norway

Michael Madsen, Halden Prison (extract of the film), Halden, Norway

There’s no life sentence in Norway, the longest period of time a convict can spend in prison is 21 years. It is thus in the interest of the country that the prison system focuses on rehabilitation and ensures that an inmate goes back in the community as a better person. The strategy seems to pay as, nationwide, Norway has one of the lowest recidivism rates in Europe, just 20% after two years, compared with around 50% in England.

Regarded as the most humane prison in the world, Halden Prison is a maximum-security prison located in the middle of a forest in the South of Norway. There are no bars on the windows and prisoners are not locked up during the day. They have individual cells with tv and a private bathroom.

During the day, inmates work or study and are encouraged to have a hobby, whether it’s knitting, playing football, being in a band or cooking pasta. Guards don’t carry weapons and are incited to eat meals, play sport and otherwise interact with the prisoners as often as possible to create a sense of community. The prison even has an art budget.

There is also a wooden house with garden for prisoners to host their families overnight.

Nevertheless, it is still a prison where men are deprived of their liberty.

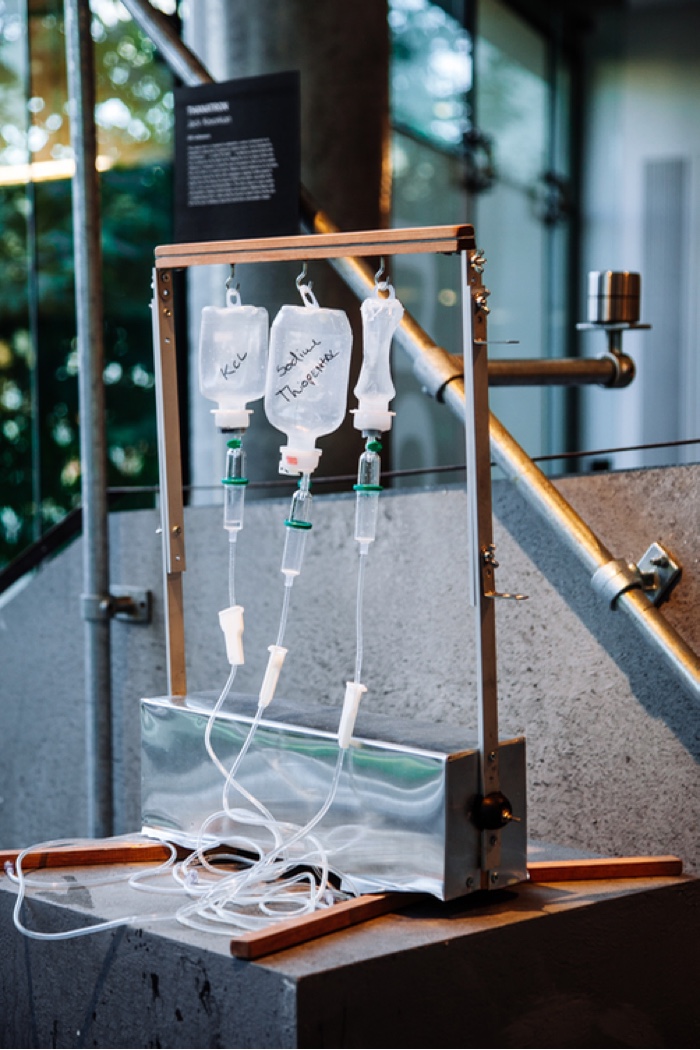

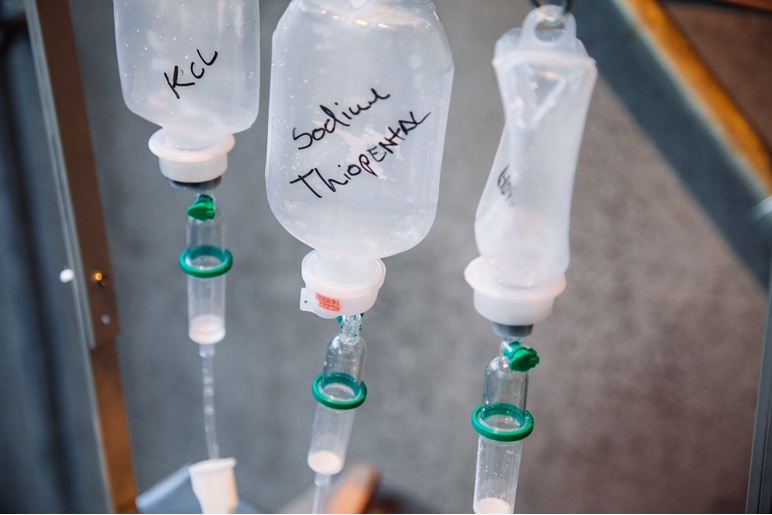

Jack Kevorkian, Thanatron, at Science Gallery Dublin

Jack Kevorkian, Thanatron, at Science Gallery Dublin

The Thanatron (‘death machine’ in Greek) was devised by medical pathologist Jack Kevorkian, to help terminally ill people end their lives peacefully.

The system is constructed out of household tools, toy parts and other bits and pieces easy to find in supermarkets and online.

The first step of Thanatron is an intravenous drip of saline solution. Then the patient presses press a button that releases a dose of an anesthetic called thiopental with a 60-second timer. The patient then slips into a deep coma, at which point the Thanatron injects a lethal dose of potassium chloride, a solution used in Belgium and the Netherlands for the purpose of euthanasia as well as in 34 states of the U.S. for lethal injection procedures. The drug stops the heart so that the patient dies of a heart attack while asleep.

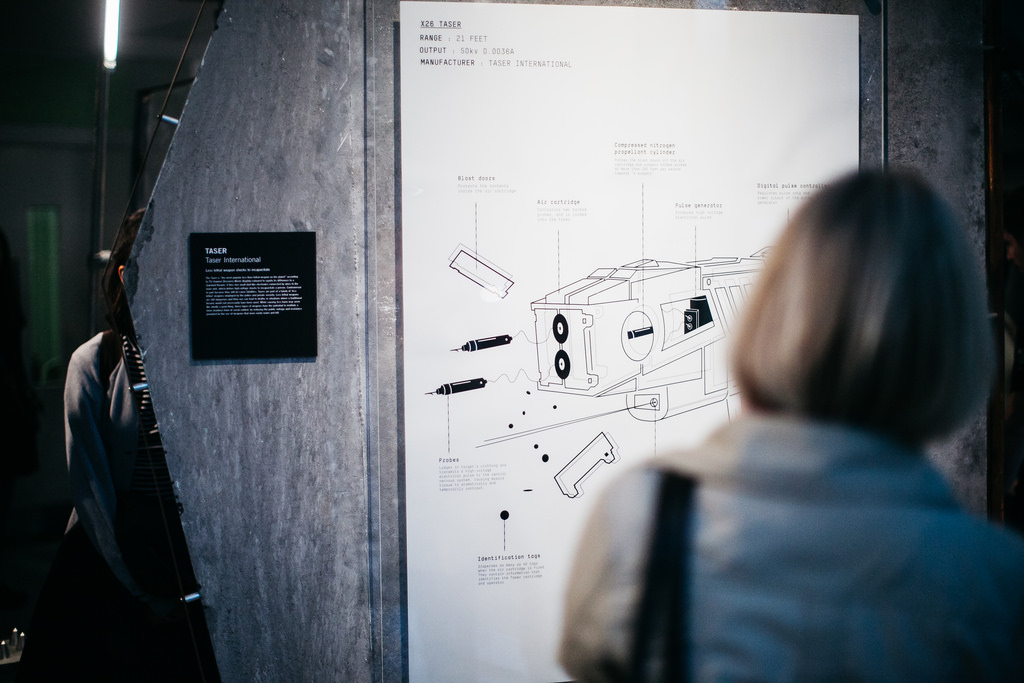

The final piece of design which purpose i find questionable is the Taser. Employed by employed by the police and private security firms, the weapon fires two small dart-like electrodes connected by wires to the main unit, which deliver high-voltage shocks to incapacitate a person. They cause brutal, extreme pain and their use have caused serious injuries and death. They are even fired at children and elderly people. While causing less harm may seem like wholly a good thing, these types of weapons have the potential to institute a more insidious form of social control, by reducing the public outrage and resistance provoked by the use of weapons that more easily maim and kill.

(To be continued…)

Design and Violence is a co-production by the MoMA in New York and Science Gallery Dublin. The show remains open until 22 January 2017.