In some rental housing across the British Isles, mould blackens parts of walls and ceilings. It takes over clothes while damp and leaks damage food items and furniture. The health of tenants living in these conditions is also affected, with some developing allergies or respiratory problems. Many claim that they receive little to no help from social and private landlords. In England only, the number of complaints about damp and leaks from social-housing tenants is on course to more than double for last year compared with 2020/21.

Video still of a participant in her sitting room where there is a hole in the ceiling from a leak

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

Avril Corroon, whose work I discovered a few years ago when she was busy making cheese using bacteria collected directly from the mould growing in London housing, is exploring damp as a crisis of nature in the home. Her new project uses the water collected from ultra-damp homes in order to fill the transparent walls of an installation, making visible how the prevalence of damp within homes has become an indicator of social inequalities in the UK.

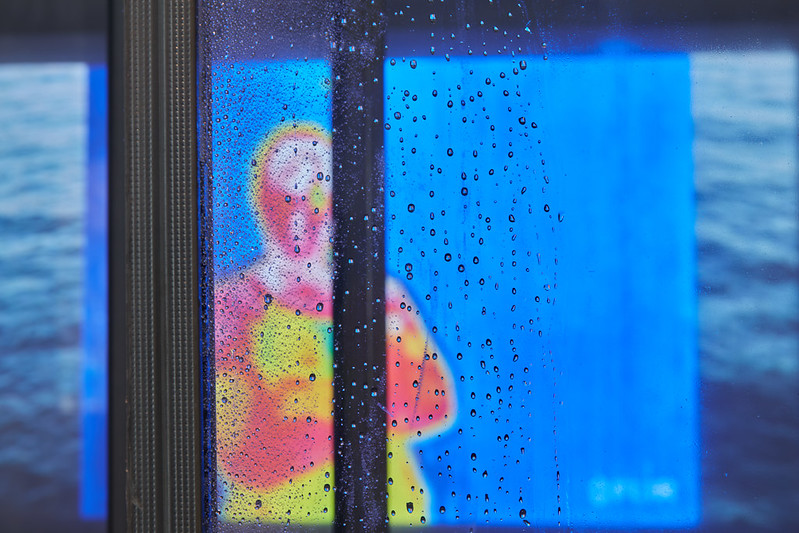

Thermal imagery with participants discussing their damp issues

Thermal imagery with participants discussing their damp issues

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

During the research phase of the project, the artist found 55 households from London and Dublin. She equipped them with a free energy-efficient dehumidifier and a 25L jerry can. Over the Winter and Spring period, participants had to empty the electric dehumidifier tank into the jerry can. When full, the can was either collected and replaced or dropped into a Got Damp collection point.

The liquid was then used as part of an art installation. Modelled on the footprint of a domestic living space, the structure is made of double-skinned clear plastic walls. The ‘damp’ collected by the households is pumped and filtered to run down the inside of the perspex walls.

The installation also features a film that documents the daily struggles of people whose domestic life is affected by damp. Their testimony is juxtaposed with thermal imagery and shots of the effects of damp on the fabric of buildings.

The experience they share is shocking: the content of open cereal boxes quickly goes mouldy, children’s asthma gets worse, rooms have to be kept heated all day lest the damp takes over the kitchen and the emotional toll of seeing that their predicaments are not taken seriously, etc.

Here is the transcript of a conversation I had with Avril Corroon a few weeks ago:

Hi Avril! For the Got Damp project, you worked with 55 households from London and Dublin. How did you find these communities?

The first part of the research was done in collaboration with TACO in Thamesmead in London. Then I had an opportunity to expand the project in Dublin with Project Arts Centre, the edition there will open on April 21st. On my first approach to finding people who would be interested, we went through the galleries network and my own social networks. We also placed adverts in local newspapers. They said things like “Do you experience damp in your home? Do you want to share your experience about it?” With the ads, I got a few people that I probably wouldn’t have been able to reach out to through my own network. I also did a set of stalls outside of shopping centres. There was just a table and posters and I was shouting “Got Damp” to passersby. A few people responded, “I have damp, yeah!” You find that people who have a hefty amount of damp often also are not being listened to by their property landlord or housing association. They are really frustrated and they do have stories to tell. They are passionate about being involved. People are being gaslit when they try to get this issue solved.

That’s how I found people in London and through word of mouth.

When the project expanded to Dublin, I approached CATU which is a community actions tenants union and I launched the project firstly to union members. In Dublin, over half of the participants are tenancy union members. They played an important role in the project because they were already thinking about damp as a collective issue. And then half of the participants might be involved in housing activism.

Why do you call damp a class and precarity issue?

There’s a mixture of reasons for damp. The damp that I’ve seen in participants’ houses is there for different reasons which can include plumbing issues, condensation issues, not having air ventilation, etc. But in a combination of that, the reason why precarity is an issue is that it is the owner of the property’s responsibility to look after the building, to ensure that there is proper ventilation and that it is a safe space to live in. Those needs aren’t being met possibly because of the demand for refurbishment that is required. However, the brunt of living in and breathing those spores is on the tenants. I think it is an issue of precarity. You are often having to stay in properties because you need a roof over your head. As a result, you take on different compromises that you probably don’t want to or that you do not really know how safe or unsafe they might be. Having someone in power over whether you have housing means that you are constantly under the stress of being evicted every time you want to raise a complaint about your precarious situation.

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

Is it a question of the law that doesn’t protect the tenants? As far as you know, is it better in other countries?

Part of it has to do with climates because both London and Dublin are wet places. Thamesmead where I’ve been working is located on reclaimed marshland. The problem is partly climatic and partly due to how houses are built. A lot of the housing has had issues with the mortar. The masonry buildings are built in a way that is not sustainable for use anymore. The cost of fixing and rejuvenating the homes is seen as too costly or too disruptive as in some cases it would involve the tearing out of walls to add in new panels.

When it comes to the legal aspects, I find that the law on housing is not very strictly enforced anyway. There was a case of Awaab Ishak, a 2-year-old who died from chronic exposure to mould in his home in London. His case has led to a law change in England which has set new deadlines for reparations that council housing has to abide by. That law is only specific to council properties but not private rentals.

You provided the households with energy-efficient dehumidifiers and support to manage damp. In exchange, they collected the water for your artwork. Can you tell us more about the process?

The participants received a 25 litres jerrycan. They are involved in the process of emptying the dehumidifier and pouring its content into the jerrycan. They form a new relationship with the water when they are holding it and watching the jerrycan being filled. I was interested to get people’s feedback on that. Some approach it in a very analytical way. A scientist or someone who has a more mathematical brain is interested in the idea of the collection of water-providing data. Others have a different, more bodily relationship with water because the water in a home contains part of yourself and of your living: what you’re washing, cooking… your breath even. There is something abject and poetic in handling a part of your fleshing wet body. I was also interested in this collection, in those moments and in the combination of all of that together.

How much water did they collect in a week or a month?

It varied extremely. Over two months, I could go three to four times to some people’s houses to collect a full jerrycan. Others had one can full after the five month period. Which is still a lot.

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

The water used in your installation looks normal, did it go through a process of purification to be so clear?

Yes, the water does look normal. The action of the dehumidifiers is to take off that excess amount of humidity. They are set to have an ideal goal of humidity level to meet. After which, they stop working. They can’t work when it is too cold either, they work a bit like a refrigerator. It’s a type of distillation that pull off excess water from the air. The air is not dirty because it is damp or because it has an association with mould. The reason why we have mould in properties is that excess moisture enters in contact with walls and cellulose wood and furniture, that is the sort of food that the mould thrives on. It is not water per se that creates mould. That water isn’t good for you, it doesn’t have minerals in it, it actually takes out bad minerals that are going through the system of the dehumidifier but it is not dangerous. There is not much use for it. Some people use it for watering their plants and it might actually be better for gardening than tap water found in some areas of London. The best use though is to pour it into your toilet tank for flushing.

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

Avril Corroon, Got Damp (installation view at TACO!) Courtesy of the artist and TACO! Photography by Tom Carter

I was looking at the photos of the installation and I was reminded of an installation by Teresa Margolles. Do you know her work?

Oh yes, you mean the work where she collected the water from the mortuary?

That’s the one! I remember feeling uncomfortable when I was in the exhibition room reading the description of her artwork. That made me wonder how I’d felt if I entered your installation. How did people react to it? Did they describe the bodily sensations they had?

I’ve hacked the jerrycans into becoming humidifiers. They are pumping the water vapour into the cavities of perspex-lined partitioned walls. It is contained in the walls that intersect the space and that you encounter as you go through the corridors. These walls occupy a domestic-sized area within the gallery. The water drips and condensation that form inside the cavities of the wall remain within the wall so the vapour isn’t escaping into the room.

In the description of the work, exercise their political voice. Did they use the results of their collaboration with you to communicate with their landlord? And say

When I conducted interviews, I used a thermal camera which showed the temperature and areas of cold and damp spots. Participants were offered the images afterwards, they could use them as data to back up claims to their landlords if they wished.

Thanks Avril!

GOT DAMP by Avril Corroon is at TACO! in London until 30 April 2023. The show will also travel to Project Arts Centre in Dublin from 20 April to 10 June 2023.

Previously: Making cheese from the black mould on your wall.