Named after Ballard‘s 1973 novel, this group show at the Gagosian London had not only a quite impressive line-up paying hommage to the British writer. It also tried to show in which ways Ballard’s “open attack on the all the conventional assumptions about our dislike of violence in general and sexual violence in particular” had been inspired by art such as his beloved Paul Delvaux or his own contemporaries as Ed Ruscha or Warhol.

But, and possibly more interesting, it aimed to analyze how he in turn influenced a generation of artists (quite literally, either Jake or Dinos Chapman claims that reading Crash was his primary motive for taking up driving lessons) and the public imagination as a whole. Ballard even made it into the English language as the adjective “ballardian”, describing “dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments”.

Crash at the New Arts Laboratory London, 1970

Crash at the New Arts Laboratory London, 1970

Ballard for instance famously saw the show This is Tomorrow at Whitechapel Gallery in 1956 which had a big impact on him. Less well-known but all the more interesting is the fact that in 1970, three years before Crash was published, he had himself set up an exhibition of car wrecks at a London gallery.

In his autobiography Miracles of Life he writes: “I ordered a fair quantity of alcohol, and treated the first night like any gallery opening, […] I have never seen the guests at an art gallery get drunk so quickly. There was a huge tension in the air, as if everyone felt threatened by some inner alarm that had started to ring. No one would have noticed the cars if they had been parked in the street outside but under the unvarying gallery lights these damaged vehicles seemed to provoke and disturb. […] By the time the show closed, […] I had long made up my mind. All my suspicions had been confirmed about the unconscious links that my novel would explore. My exhibition had in fact been a psychological test disguised as an art show, which is probably true of Hirst’s shark and Emin’s bed.”

The works in Crash at the Gagosian were not all for sale, some were borrowed from different collectors and maybe this is one of the reasons that this was possibly a very comprehensive and almost museum-like show for a commercial gallery. Some favorites:

Carsten Höller, Giant Triple Mushroom (2010)

Carsten Höller, Giant Triple Mushroom (2010)

Carsten Höller’s Giant Triple Mushroom is a sculpture which is a mashup of the fly agaric mushroom, actually three mushrooms which in Höller’s words “crash and form a new body. Fragmentation, poison, paradise, cuts and wounds”. In the background Piotr Uklański’s Untitled (Ivy Mike).

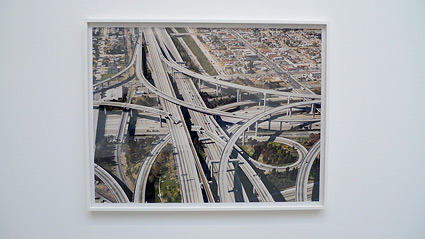

Florian Maier-Aichen, Freeway Crash (2002)

Florian Maier-Aichen, Freeway Crash (2002)

Florian Maier-Aichen’s work shows the iconic image of an American freeway flyover, bathed in California light. However, almost hidden in the complexity of the image is that some of the tracks have collapsed in what looks like a digital montage. It takes a few moments to spot and then people tend to giggle, at the futility of things maybe.

Richard Prince, Elvis (2007)

Richard Prince, Elvis (2007)

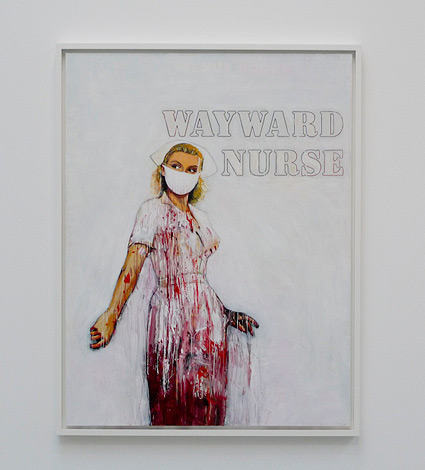

Richard Prince, Wayward Nurse (2005)

Richard Prince, Wayward Nurse (2005)

Richard Prince, the “Duchamp of the Muscle Car” as the New York Times calls him, shows one of his car bodies which are frozen in the state one would find them in at a car body shop. As he says, “they’re in that state before you’re actually finished, just before you paint it, and I’ve always loved that look on teenagers’ cars: nine coats of perfect paint on the hood but then the doors are left bare metal because they never got around to it.”

Chris Burden, L.A.P.D. Uniform (1993)

Chris Burden, L.A.P.D. Uniform (1993)

Chris Burden’s L.A.P.D. Uniform, a reaction to the 1992 riots in Los Angeles is a great piece because it takes some time before one realizes that the uniform alone is actually as big as a person, tailored for a gigantic cop (in fact seven-feet, four-inches tall). Employing the radical change in scale he often uses, it was originally exhibited as 30 identical pieces, each with a real gun. It’s very intimidating but at the same time hints at the ambivalent role of the police in the protection from violence and its infliction.

Might be worth watching Frederick Wiseman‘s Law and Order (1969) again, which talks about the same topic with the means of documentary filmmaking. Or get rid of police altogether as a piece of performance art?

Roger Hiorns, Untitled (2009)

Roger Hiorns, Untitled (2009)

Roger Hiorns, of Seizure fame, submerged two automobile engines into a copper sulphate solution to create sculptures covered in the the same blue crystals he covered a whole council flat in to years ago. A second piece consisted of contact lenses on the ground and, invisible as they were, I unfortunately stepped into them. It wasn’t the first time this had happened, so it was OK.

Tacita Dean, Teignmouth Electron, Cayman Brac, Ballard (1995)

Tacita Dean, Teignmouth Electron, Cayman Brac, Ballard (1995)

Actually quite a beautiful piece of work. Tacita Dean had become fascinated with the story of British businessman and sailor Donald Crowhurst and in fact saw him as a character from a JG Ballard story. Crowhurst participated in the Golden Globe sailboat race of 1968 on his bar called the Teignmouth Electron, a 40-foot trimaran designed by Californian Arthur Piver. He started the race, intending to loiter in the South Atlantic for several months while the other boats sailed the Southern Ocean, falsify his navigation logs, then slip back in for the return leg to England. Things did not go as planned, however, he disappeared on June 29th and the trimaran was found 11 days later. Crowhurst had apparently committed suicide and onboard the boat his writings during the voyage were found, more than 25,000 words attempting to construct a philosophical reinterpretation of the human condition that would provide an escape from his impossible situation.

In 1995 Tacita Dean went to Cayman Brac where the boat is still sitting today and took this photo. In 1998 she sent it to JG Ballard, asking him how he felt about Donald Crowhurst. He “replied that he’d never taken much notice of Crowhurst and thought him a foolish man, but that the boat reminded him of the crashed Second World War aircraft they were still finding in the jungles of Pacific islands.” Dean says that this is “the heart of Ballard’s vision – the object at odds with its function and abandoned by its time.”

Since then, Dean had corresponded with Ballard about her project to find the Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) in Utah. He sent her an essay which begins with “What cargo might have berthed at the Spiral Jetty?”, saying that Ballard “connected with Smithson and believed him to be the most important and mysterious of post-war American artists.”

Jeff Koons and Glenn Brown

Jeff Koons and Glenn Brown

Futures clash in this juxtaposition of Jeff Koons’ New Hoover Convertibles (1986) and Glenn Brown’s The Pornography of Death (Painting for Ian Curtis) After Chris Foss. Two appropriations: Koons’ ironic view on domestic technologies the mystification of the mundane. Glenn Brown, almost the other way around, in this case using sci-fi imagery from famous illustrator Chris Foss.

Brown argues that “to make something up from scratch is nonsensical, images are a language. It’s impossible to make a painting that is not borrowed — even the images in your dreams refer to reality.”

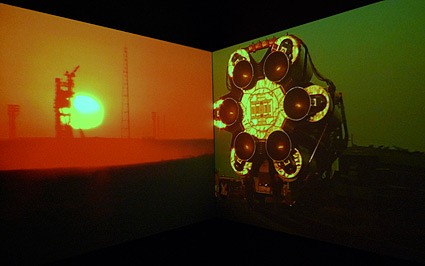

Jane and Louise Wilson, Proton, Unity, Energy, Blizzard (2000)

Jane and Louise Wilson, Proton, Unity, Energy, Blizzard (2000)

Proton, Unity, Energy, Blizzard is a four-screen installations which represents an exploration of the architecture of the three main Russian launch sites, Proton which follows a Proton rocket to its launch site, Unity (Soyuz) the launch site for all manned space missions and Energy (Energia), a site abandoned for over ten years, originally designed to carry the Russian space shuttle Blizzard (Buran).

Paul McCarthy, Mechanical Pig (2003-2005)

Paul McCarthy, Mechanical Pig (2003-2005)

Lastly, Paul McCarthy’s amazing Mechanical Pig which unfortunately wasn’t operating (see it in motion here). The Guardian wrote some beautiful words about it in the past: “So lifelike is this many-teated sleeping pink sow, breathing sonorously and twitching a curly tail in her porcine dream, that only her cumbersome life-support system of electronic gizmos, hydraulics and computers convinces us she’s not real. Even her sphincter puckers in her sleep.” And indeed, the pig is perfect. And it’s also the fact that the technology is not hidden but an amount of over-engineering becomes an essential part of the piece and talks about the way that our dreams are being created.

More images. Also don’t miss Ballardian, a blog about everything JG.

Related: Paul McCarthy at the S.M.A.K.