Cinema Sim – Narratives and Projections, currently on view at Itau Cultural in Sao Paulo, is one of those rare exhibitions you exit wearing the silliest smile on your face. You are happy. The selection of the artworks is faultless, each piece gets the space it deserves and needs, and the theme of the exhibition with tis mix of edginess and approachability is particularly appealing.

View of one of the exhibition rooms. Image courtesy of Itau Cultural

View of one of the exhibition rooms. Image courtesy of Itau Cultural

Cinema Sim – Narratives and Projections is not an exhibition about cinema, but rather about the idea and concept of cinema and how contemporary artists imbue their works with creative and aesthetic principles that hark back to the cinematic language and its means of expression, wrote Curator Roberto Moreira S. Cruz in the catalog of the exhibition.

The 18 works selected explore three core themes: narrativity, the illusion of visualness and the reference to the kinetic experiences of the pre-cinematic era.

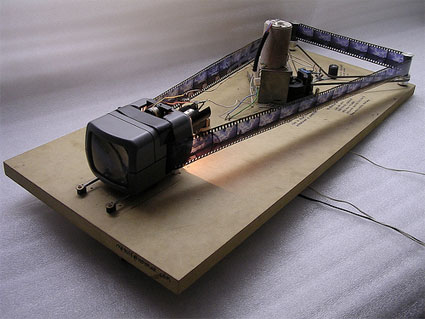

Milton Marques, Untitled

Milton Marques, Untitled

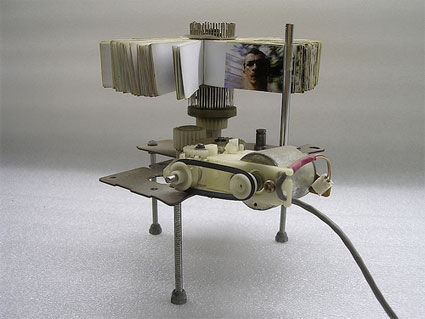

To create its little cinematic devices, Brazilian artist Milton Marques uses all kinds of discarded technological instruments rummaged through second-hand shops: optical elements, step motors, printers, copy machines, fruit squeezers, cameras, mini-tv, etc.

There is magic not only in the way he infused a new life into the abandoned objects but also in the outcome of his manipulation. Itau Cultural was exhibiting three of his sculptures:

To activate the first one, you have to insert a coin in a slot and the photos of a photographic film will (almost) appear to become animated inside a tiny tv-like screen. Because the whole mechanism is exposed, the spectacle is also present out of the screen.

Milton Marques, Untitled

Milton Marques, Untitled

A mundane fruit squeezer powers another of Marques’ work.

Milton Marques, Untitled

Milton Marques, Untitled

Marques’ pieces provide some further thoughts on the analogy/dissimilarity between cinema and the 18 visual art works at Itau Cultural. Of course, the devices that project the moving images are quirky and ingenious. They clearly refer to cinema but even the space where they are exhibited is miles away from what you would expect to see in a movie theater. Visitors are not spectators bound to their seats, they can circulate and move from one screen to another. The screens themselves are worth a closer look. They do not come necessarily in the typical shape of a large-scale two-dimensional white canvas. As the rest of the exhibition demonstrates, some of these screens are tiny, one is the surface of a light bulb, one is made of sand, another one moves. Sometimes the images are split over multiple screens.

89 Seconds at Alcázar, a work by The Rufus Corporation + Eve Sussman, might look at first sight as almost cinematographic but it refers to other artistic disciplines such as performance, photography and painting. 89 Seconds at Alcázar is almost as haunting as the artworks it takes its inspiration from: Diego Velasquez‘s seventeenth-century masterpiece, Las Meninas.

Video Still from “89 seconds at Alcázar” by Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation. Photo: Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation

Video Still from “89 seconds at Alcázar” by Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation. Photo: Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation

Velasquez’s painting is one of the most studied and discussed in the history of art. He shakes up the traditional rules of the pictorial architecture by placing King Philip IV of Spain and Queen Mariana both “outside” the painting as observers of the scene and “inside” the space through their reflection in the back wall mirror. Besides, he became one of the first painters known to address his own identity as artist by portraying himself in the act of painting the canvas.

In the ten-minute high definition video 89 seconds at Alcázar, the court of Spain is animated. Its protagonists murmur and whisper in each other’s ears, they move in a slow choreography across the space to finally take up their position in the painting. But unlike in the original artwork, the scene is envisioned from Velasquez’ perspective.

Jeff Wood as Philip IV, King of Spain. Production Still from “89 seconds at Alcázar” by Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation. Photo: Benedikt Partenheimer for The Rufus Corporation

Jeff Wood as Philip IV, King of Spain. Production Still from “89 seconds at Alcázar” by Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation. Photo: Benedikt Partenheimer for The Rufus Corporation

The fact that the protagonists in baroque wardrobe do not look very Spanish is a bit uncanny. That detail left aside, the instant frozen in time by Velasquez’s brush is brought back to life true to its original objective: to capture a scene in the everyday life of the royal family.

Rosângela Rennó‘s Frutos Estranhos delicately plays with our perception. Each image, displayed inside a tilted portable DVD player as if it were a picture frame, presents what looks like a static image. Yet, because sound has been added and because the images have been edited and digitally manipulated, viewers have the feeling that they can perceive some type of subtle movement in photos.

View of Rosangela Rennó’s Frutos Estranhos in Itau Cultural exhibition space. Credits: Cia de Foto

View of Rosangela Rennó’s Frutos Estranhos in Itau Cultural exhibition space. Credits: Cia de Foto

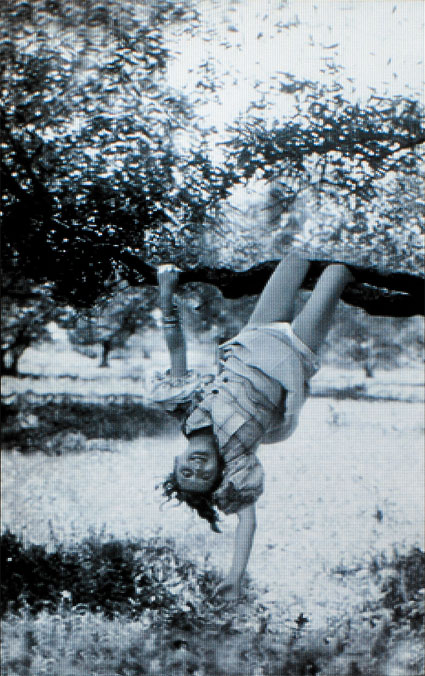

Menina, by Rosângela Rennó

Menina, by Rosângela Rennó

In the early ’70s Anthony McCall developed solid light films, which emphasize the sculptural qualities of a light beam as it comes in contact with particles in the air. In You and I, Horizontal III, he uses vapor from a haze machine to shape an almost tangible 3D ray.

Anthony McCall, You and I, Horizontal III. More images at the Serpentine Gallery. Installation view at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, 2007. Photograph Steven P. Harris

Anthony McCall, You and I, Horizontal III. More images at the Serpentine Gallery. Installation view at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, 2007. Photograph Steven P. Harris

I still have to meet someone who would remain indifferent to Hiraki Sawa‘s charming Going Places Sitting Down. I am not going to comment on the work. Instead, let me point you to the video over here.

Hiraki Sawa, Going Places Sitting Down, 2004

Hiraki Sawa, Going Places Sitting Down, 2004

There is much more to see at Cinema Sim – Narratives and Projections. The exhibition runs until December 21 at Itau Cultural, Sao Paulo. If you can’t make it to Sao Paulo before the show closes, a consolation prizes awaits you: the catalog is available online as a PDF (now you’ll just have to click around, cuz it is burried somewhere inside one of those Flash obnoxiousness.)