One of the most exciting exhibitions I saw this year (not that I’ve seem many due to you know what) is Bigger than Myself. Heroic Voices from ex-Yugoslavia at the MAXXI, the national museum of 21st-century art in Roma.

Lenka Đorojević and Matej Stupica, Monomat/Mon-O-Matic, 2015. Photo: Martin Lovšin Schintr, Arhiv

Bigger than Myself. Heroic Voices from ex-Yugoslavia, installation view. Photo: Musacchio, Ianniella & Pasqualini for MAXXI

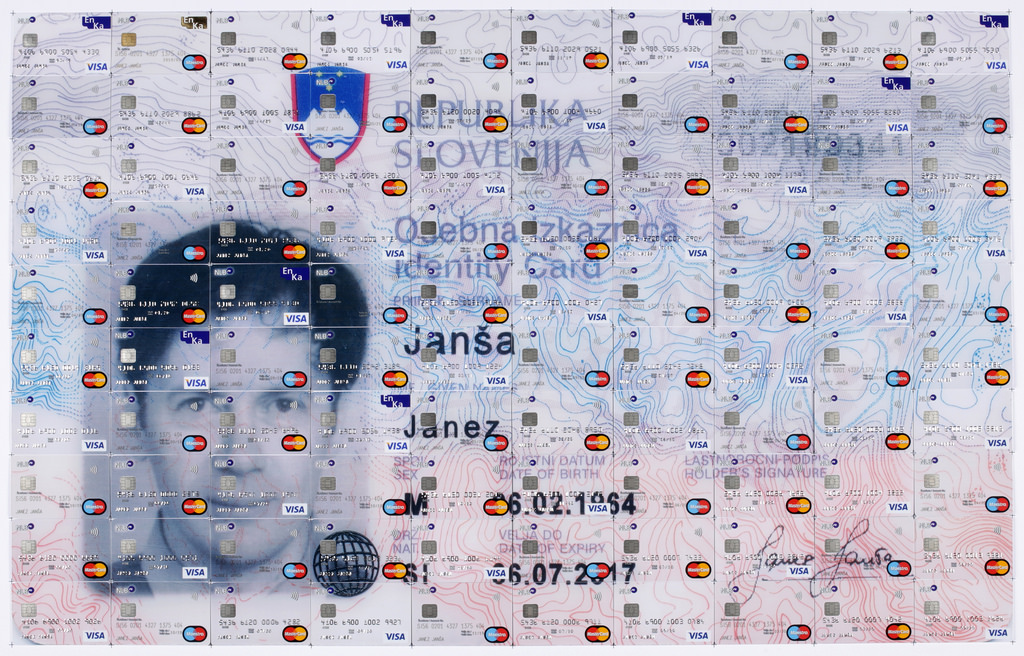

Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša, All About You, 2016

Some 60 contemporary artists coming from all the countries that used to form Yugoslavia narrate and interpret a territory that was built on ideals of solidarity and brotherhood. Today, the area oscillates between neoliberalism and utopia, multiculturalism and nationalisms, plans for the future and traumas of the past. The ideas explored in the artworks are universal enough that they never feel insular. They talk about human rights, workers’ rights, gender equality, acceptance of the other and the kind of place Europe should be: a space where different identities, cultures and beliefs can find common grounds and enter into a fruitful dialogue.

Bigger than Myself. Heroic Voices from ex-Yugoslavia is a great show. I almost didn’t go. I entered thinking “Let’s hope this is not another Marina Abramović show!” (nothing against the lady but I’ve seen my fair share of Abramović exhibitions over the past few years) and exited the show happy to have spent a couple of hours in the company of artworks that were bold, socially-engaged and smart. This review focuses on the pieces that look at labour conditions, migration and the ghosts of past conflicts.

The show opens with Igor Grubić’s portraits of “Angels with dirty faces” on one of the facades of the museum.

Igor Grubić, Angels with dirty faces. Photo: Musacchio, Ianniella & Pasqualini for MAXXI

Igor Grubić, Angels with dirty faces, Portrait, 2016

When Grubić was in Belgrade in October 2000, he heard that the miners in the coal mining area of Kolubara (in today’s Serbia) had started to strike in protest against the regime of Slobodan Milošević who was then president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The coal mine produced 50% of electricity in the country so the miners’ action helped precipitate Milošević’s fall. The event also marked the demise of socialism in former Yugoslavia.

The work is inspired by Wim Wenders’s 1987 film Wings of Desire, in which angels descend to Earth to comfort mortals in distress.

Marko Tadić & Miro Manojlović, Concrète Machines (13 Pieces for Prvomajska), 2018

Marko Tadić & Miro Manojlović, Concrète Machines (13 Pieces for Prvomajska), 2018

In 2018, Marko Tadić asked Miro Manojlović to create, based on the drawings of the space and machinery of an abandoned factory in Kapran, music compositions that would eventually be played on the machines. The machinery that had once produced completely different sounds, became acoustic instruments with a broad tonal range over the course of the performance.

For a few hours, the performance filled with life and sound the industrial space, as an homage to the hundreds of workers and their families who had formed a community there.

Lenka Đorojević and Matej Stupica, Monomat/Mon-O-Matic, 2015

Lenka Đorojević and Matej Stupica, Monomat/Mon-O-Matic, 2015. Photo: Martin Lovšin Schintr, Arhiv

A reflection on the automatisation of office work, Mon-O-Matic is based on the research of the working conditions of the cognitive precariat (made of journalists, translators, programmers, graphic designers, video editors, “content creators” and all the freelancers who work mostly online) which are characterized by the monotonous repetition of gestures and the atomisation of tasks that makes humans behave likes machines.

Over time, the office desk instruments in the installation start to shatter and break apart as a mirror of the human workers whose mind becomes numb and eroded under the strain of the automatisation of their work process.

A number of works looked at asylum seekers and migrants from the Middle East and

Africa who crossed the Mediterranean looking for a better life in Europe. Taking in foreigners and protecting those suffering from persecution has a long history in European civilisation, which considers the protection of human life and the stigmatisation of discrimination as fundamental principles. At least that is the theory and it is being obstinately eroded with each new arrival of migrant boats.

Zoran Todorović, Integration, Illegal people project, 2017. Video documentation of project – still frame

Zoran Todorović, Integration, Illegal people project, 2017. Video documentation of project – still frame

Zoran Todorović, Integration, Illegal people project, 2017. Video documentation of project – still frame

Zoran Todorović collected urine from people who were living in a refugee center in Belgrade and waiting for the authorisation to make their way to EU countries. Todorović used their urine to make craft beer. The beverage was intended for consumption by the audience in “first-world” countries as part of a performance lecture.

The work opened up the problem of the status of refugees and the human body, which, under certain conditions, become mobile and admissible in European countries, as long as they respond to capitalist dynamics.

“At the end of my project, some people who stayed longer knew that I was making beer, so they were willing to help, which is to pee in the urinal for my project. In the end, it only took four days to collect urine. On the one hand, I had to call it the end because there was a very open war with Doctor Without Borders.” (…) “I collected only 10 litres of urine, though it is not a little amount, at the first moment I expected much more, if I could stay in the centre a bit longer.” (…) “Those problems are the symptoms of something I can hardly articulate, something that relates to the secret of our state. What is the problem if refugees choose to pee here or there?” (…) “Who can tell where the right place is for peeing? What does ‘peeing’ mean in that context?”

Alban Muja, Family Album, 2019

Alban Muja, Family Album, 2019

20 years after the end of the Kosovo War (1998–1999), Alban Muja selected photographs of child refugees taken during the war. Published in media around the world, these images became emblematic of the trauma and pain inflicted on people caught in a conflict. Muja tracked down the individuals in the photos. Now adults, the subject of the photos tell him what they know about the moment when the photos were taken and the role these images have played in their lives.

Family Album reminds us that behind the circulation of images lie personal narratives. The work also highlights the ambiguous economy surrounding the distribution and circulation of images and their role as agents of a wider political and media story that operate beyond the control of the subjects represented.

Nika Autor, Newsreel 65 – “We have too much things in heart”, 2021

Nika Autor, Newsreel 65 – “We have too much things in heart”, 2021

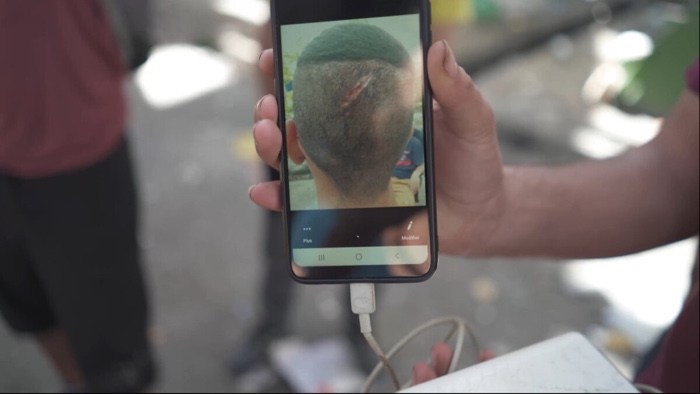

“If the forests could speak, they’d dry out from sadness,” said Moseeben, a migrant on his way to a (hopefully) better life. It takes between ten and fifteen days to cross that forest and reach the European Union. Located in the proximity of Italy, Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia, the forest is also a place to hide: remaining invisible means a slight chance for refugees to stay alive. The refugees often define their journey as a “game”, an exercise in hiding from the gaze of others.

The video installation Newsreel 65 – “We have too much things in heart” presents the daily attempts, hardships and failure of refugees to cross the border and reach the European Union.

The violence described by the migrants is harrowing. The police treat them with brutality and pretty much any basic human right is denied to them.

The twenty video fragments, which present the testimonies of refugees caught before the border of the European Union, presents a painful contrast with the toxic vocabulary and images used by vile European politicians to describe human beings who are fleeing wars and persecutions.

Lana Čmajčanin, FN M1910, 2014. Photo: Musacchio, Ianniella & Pasqualini for MAXXI

The FN Model 1910, also known as the Browning model 1910, was the handgun used by Gavrilo Princip to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. The event led to the beginning of WWI, the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the birth of the first Yugoslavia. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand is one of many historic events where FN M1910 was used.

Lana Čmajčanin turned an object into a historical subject in order to explore how arms production and the military industry create their own historical narratives. The work tells a story that symbolised the political situation in Europe of the early 20th century as well as the contemporary world, defined by the global market of weapons and the state of permanent war.

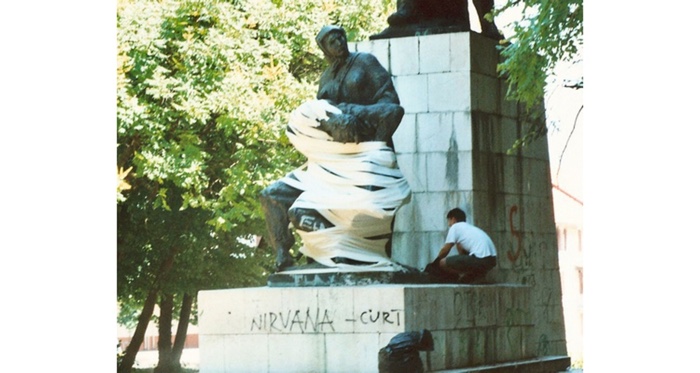

Siniša Labrović, Bandaging the Wounded, 2000

On the Anti-Fascist Struggle Day on the 22nd of June 2000, Siniša Labrović bandaged a sculpture dedicated to the anti-fascist fighters of WWII. The monument shows a woman who holds a wounded partisan in her arms. The statue is one of the thousands of partisan monuments that have been damaged by Croatian nationalists in the 1990s.

Dalibor Martinis, Blasted Lenin’s Coat, 2012. Photo: Musacchio, Ianniella & Pasqualini for MAXXI

Blasted Lenin’s Coat evokes an event that took place on the 1st of April 2009, when a bomb blew a hole in a bronze statue of Lenin in St.Petersburg. Twelve years later, the artist used industrial felt to sew a coat that would fit Lenin’s statue. He used an explosive to make a hole in it.

Marko Peljhan and Matthew Biederman, We Should Take Nothing For Granted, 2014. Photo: Musacchio, Ianniella & Pasqualini for MAXXI

The title of the work We should take nothing for granted is based on Dwight D. Eisenhower’s farewell address of 1961 wherein he warns of the dangers of an unbridled military-industrial complex, the extinction of creative free-thinking within higher education and the extraction of natural resources without consideration for their renewal.

When Marko Peljhan and Matthew Biederman started working on WSTNFG, that address sounded premonitory. With Edward Snowden’s surveillance revelations, the idea of an unchecked military-industrial complex was not a conspiracy anymore. It was real and dangerous.

The WSTNFG fills a whole room with instruments and documents that reveal the importance of control and control ability of electromagnetic waves and urges examination about possession, utilization and misuse of global information communication infrastructure.

The project treats the electromagnetic spectrum as a commons, something that belongs to everybody. It also reflects on the conditions for the development of the “alert and knowledgeable citizenry” Eisenhower called.

Ištvan Išt Huzjan, Planetary Performance: From Sunrise to Sunset, 2019

Ištvan Išt Huzjan suggested to curator Olivier Bellflamme that they travel to the antipodes of the Earth. The artist followed the Sun’s movement in the Peruvian Andes, while the curator followed the solstice at the opposite side of the planet, in Laos. When the Sun was setting for the artist, it was rising for the curator.

And at the precise moment when they were located as far away from each other as possible, they took a photo: Huzjan photographed the sun, disappearing halfway and Bellflamme made a picture of the sun, halfway on its rise.

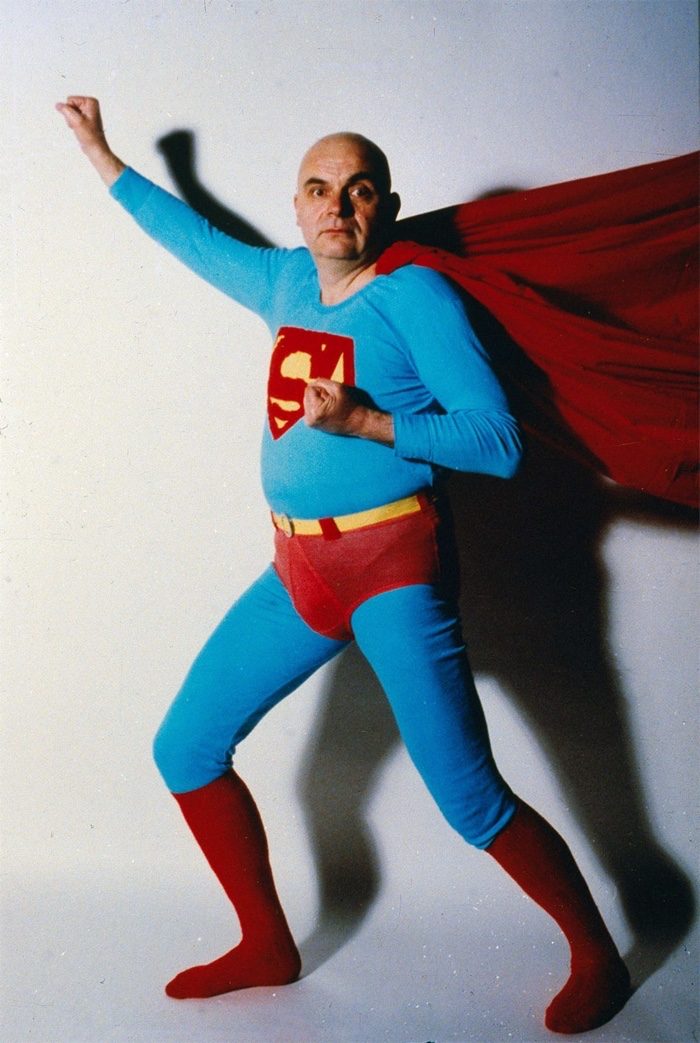

Tomislav Gotovac, Superman, 1984 (photo)

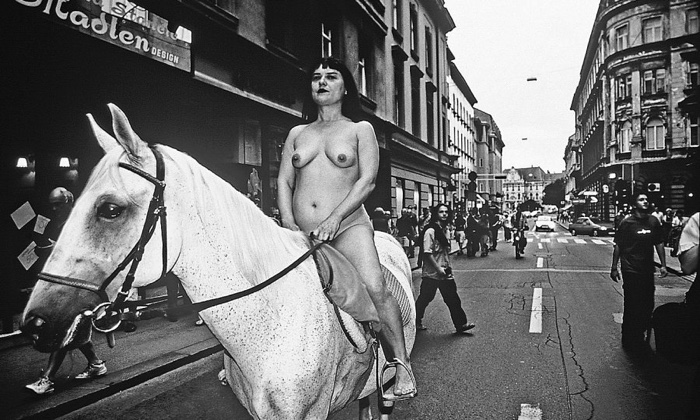

Vlasta Delimar, Lady Godiva, 2001. Zagreb

Hristina Ivanoska, Document missing, n. 2,

Bigger than Myself. Heroic Voices from ex-Yugoslavia, curated by Zdenka Badovinac with associate curator Giulia Ferracci, remains open at MAXXI in Rome until 12 September 2021.