Fernando Orellana (whom i interviewed a few years ago) is currently having a solo show at the Ben Bailey Art Gallery, Texas A&M University-Kingsville.

The line-up of robots, sculptures and installations the New York artist and assistant professor at Union College summoned to his show is pretty impressive: there are suitcases maniacally monitoring the space, dysfunctional toys, a bird that talks in its dreams, people trying to jump the queue, Adam, Eve, even the Spaceman is there. Each of them provided me with the perfect excuse to ask Fernando to tell us about some of his latest pieces.

View of the exhibition space. Image by Patrick Flores

View of the exhibition space. Image by Patrick Flores

Me and You, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Me and You, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

You currently have a solo show at Texas A&M University-Kingsville. Can you tell me how the exhibition came to be? Is this a solo show with a curator who selectioned existing pieces and commissioned new ones? Or were you the captain of the enterprise?

The story behind the exhibition starts five years ago while I was a graduate student at the Ohio State University. While there, I met Jesse De La Rosa, a gifted painter who is as passionate and crazy about making art as I am. We became fast friends, staying in contact over the years. Last year he approached me to put on an electronic art exhibition at Texas A&M University-Kingsville where he is an Assistant Professor of printmaking. He gave me complete freedom, with the condition that I would send him, in his words, “robots, robots, robots!” Beyond that, I could do whatever I like with the 3000 sq ft. Ben Bailey Art Gallery. Thanks again Jesse!

No Cuts, No Buts, No Coconuts, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

No Cuts, No Buts, No Coconuts, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

How come so many works of yours emerged this year? It’s only March! Did you get a sudden burst of energy or were you working on the pieces for a long time? Do you see these pieces as a sole body of work or are they all individual and almost unrelated?

Last year was my first sabbatical from Union College, which allowed me lots of time to develop completely new work, travel, and participate in a couple of residencies. I designed the new work for the exhibition in Texas last year during my residencies at the Vermont Studio in Johnson, VT and the Takt Kunstprojektraum in Berlin, Germany. It was all finalized this year during the months of January and February.

I do see these new artworks as one body of work, though it isn’t quite done yet. I have three other pieces in the studio that need to be completed and they are of the same vein. Though they do range slightly in conceptual models, I believe that all of this new work shares the same aesthetic in the use of materials, the technology within, and emphasis on minimalism. After these works are complete (by the end of the Summer), I’ll be moving on to new ideas, which will involve creating robotic vessels and technological interfaces for the dead. Stay tuned!

Corpus Callosum, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Corpus Callosum, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

I certainly shall. Let’s start the tour of the Texas show with Corpus Callosum. What do the birds tell to each other exactly? Where do the words they tell each other come from? Why did you call the work Corpus Callosum?

The artwork Corpus Callosum was born from my research and interest in dreams. I like to believe that we are living two separate lives, one in the dream world, and one in the waking world. I find it fascinating that, for the most part, we forget about our waking-selves in our dreams and forget about our dream-selves in our waking-life. This maybe why we rarely understand our dreams. The narrative inside the dream world is as complex as the one in our waking world. If we could drop a person’s consciousness randomly into another person’s body for a couple hours, and then, after the fact, asked them what was going on in the life of the body they inhabited, I suspect they wouldn’t have a clue what was taking place. They could probably only report bits and pieces of the entire narrative. Especially if all the rules of normal physics did not apply like in our dream universes.

Corpus Callosum, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Corpus Callosum, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

I know the whole thing sounds crazy, I definitely concede that. But once you push through the ridiculous, there are some interesting questions and possibilities that surface. For me, one of the questions I kept returning to was what would our waking self and our dream self talk about if they could have a conversation. My response to this question was creating Corpus Callosum.

Corpus Callosum is the anatomical part of the brain that connects the left hemisphere with the right hemisphere. It is the information superhighway of our minds, pushing data back and forth. I thought that was a nice title to frame the premise of the piece.

The words that the birds speak to each other are a list of phrases I wrote. Each bird has about fifty phrases that it can randomly choose from. Some of the phrases yield specific behaviors and others do not (i.e. if a question comes up, the bird will face the other bird). The waking bird’s dialogue is grounded in this world, based on the ego and focusing on daily issues relating to errands, anxiety, and other common real-world problems. The dream bird’s phrases branch from the illogical; scenarios that might be found in dreams or are associated with the Id.

Paradiso, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Paradiso, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Paradiso, 2011

Paradiso, a piece where Adam, Eve and an astronaut face tiny tv screens, uses a database of character dialogue. And the result is pretty strange. Where does this database come from? What is the scenario in Paradiso? How did the spaceman come to find himself between Adam and Eve? What did you try to achieve/communicate with this work? I have even more questions but i guess it’s better if i stop here!

Why did you stop?! More! More! More!

Paradiso stems from my childhood. As a toddler, I remember my mother telling me the story of Genesis, specifically the fable of paradise and the Garden of Eden. To a kid, with a hyperactive imagination, this story was really fun to entertain and explore. Amongst other things, what I wondered then, and still do now, is what Adam and Eve talked about before they were expelled from paradise.

At the same time, for a couple years, I have wanted to make a piece that generatively made a television show; specifically a reality television show. I’m not sure why, I guess I just thought it would be funny. In the story of paradise I discovered my reality-tv actors. In Adam’s character I imagined the beta human, completely satisfied and accepting his surroundings, and yet, confused and bewildered by everything. With Eve I found the desperate scientist, thirsting for knowledge and answers to her endless stream of questions and criticism. Together I found them to be an interesting whole, comprised of what is in all of us.

Then there is the spaceman. The mysterious spaceman, who tries to relate, but is out of touch or perhaps too busy to really connect. Yet, he is completely enamored with both of them, always encouraging them to move forward, and helping in unrelated ways. With one unbending truth: his spacesuit is totally awesome.

Paradiso, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Paradiso, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

Paradiso, 2011

Paradiso, 2011

I wrote a good portion of the dialogue for all three actors myself. The rest of it came from a brainstorming session with my wife, Melinda McDaniel, and four of our artist friends, Heather Willems, Seamus Liam O’Brien, Nora Herting, and Gregor Wynnyczuk. I asked them all, “What would Adam, Eve, and the Spaceman talk to each other about”? After a couple hours of deliberating, one or two bottles of wine, and some technology clarifications, we came up with a list of phrases. We then took turns acting out the scripts, embodying the characters, and noting if the phrases worked with each other. The exercise was great, allowing me to see the script live, much like a director of a television program does.

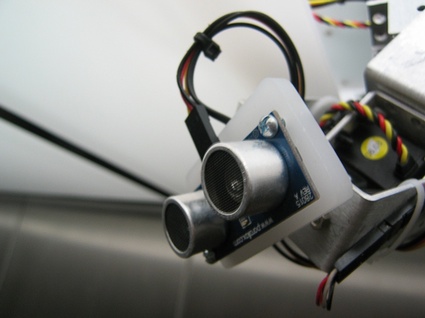

The whole thing is works using a Mac-mini, Processing, and some flavor of an Arduino. The computer program I wrote decides at random who will speak, what direction they will face, and what they will say. The resulting real-time show can only be described as surreal and a bit creepy. There are long moments in the show in which the doll’s avatars sync up in dialogue perfectly. Much like dada poetry, they arrive at insightful windows into the nature of our relationship with one another, and, perhaps, with the spaceman who we may or may not branch from.

In the future, I plan on broadcasting the live video feed through the internet so people can tune in whenever they like. That will likely happen the next time I exhibit the work.

The Living, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

The Living, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

The Living, 2011

There’s no description of The Little Houses and The Living on your website as i’m writing. They both look great. Really great (note that my enthusiasm is sincere.) I know you’re busy updating the website but if you find time to tell me something about them i’d be very grateful….

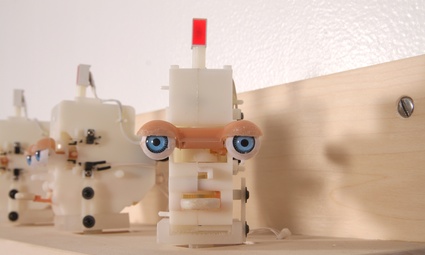

The Living draws inspiration from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which speaks of the nature of our perception and delusion with reality. The six large heads in this sculpture cannot look behind themselves. Speaking to each other with bursts of light emanating from their mouth, they can only look forward and side-to-side. The large light bulbs on their heads are symbolic of both their consciousness and the sun that blinds them from truth. The wheels that are fastened to their cribs allow them the potential to escape at any moment, and yet, they do not; they remain happily anxious in the bliss of ignorance.

In many ways, The Living is a sketch for a much larger piece I have planned. The subject matter of that future piece will be different, but the use of materials and stylization will likely remain the same. I also think that it is one of my first successful attempts at blending my painting imagery with my sculpture. If you ask me what my sculpture will look like in five years, I would point to this piece.

The Little Houses, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

The Little Houses, 2011. Image by Patrick Flores

The Little Houses, 2011

The Little Houses, 2011

The Little Houses is a piece about the dwellings we all live in. In some ways it is a continuation of my piece 8520 S.W. 27th Pl.. We live out our lives in enclosed spaces, looking out through our windows and our doors and our peepholes and our video screens. Inside we live in separate but intertwined universes, completely aware that we are helplessly out of control. We distract ourselves just enough with different flavors of pleasure and erotica, so as not to be driven mad by the desperation of it all. Tomorrow, we fall away into our appointment with oblivion. We might as well tune in the Disney channel to pass the time. Again.

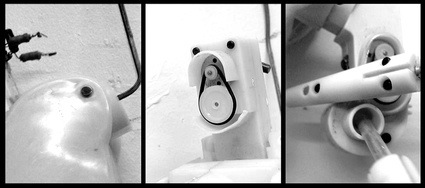

Elevator’s Music, 2007

Elevator’s Music, 2007

Elevator’s Music, 2007

Elevator’s Music, 2007

While clicking around your website i came upon Elevator’s Music which isn’t included in the exhibition at Texas A&M University in Kingsville, Texas but i’m still curious about it. I read on the project page that you installed the work in an elevator of the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College. How did people react to the robots? Didn’t they feel threatened? Did you have to warn elevator-goers of their presence or could you leave them the surprise? Btw, do they still put music in elevators? Or is this just a legend?

In Manhattan, a couple days ago, I saw a DJ playing records in an elevator, so yes, I think they still put music in elevators.

If I had it my way, I would embed robots in all of the elevators! I cannot think of a better place for a robot to live. There is a consistent source of power, the weather never changes, someone is always around to keep an eye on them, and they are far more entertaining than elevator musak. If any elevators out there want a robot, please send me an email. Long live the robots!

I have learned a couple things about installing robots in an elevator. First, I learned that a very small portion of the population is 100% not cool with hanging out in a small enclosed room with four curious robots. This same minority group did feel threatened, but only because they thought big brother was watching them (which he wasn’t) or that laser beams were going to disintegrate them (which is crazy). I suspect that these are the same people who are afraid of spilling salt, breaking a mirror, or were very disappointed when they learned Santa Clause was not real.

On the other hand, I learned that most of the population is completely fascinated with robots in elevators, so much so that they tend not to leave the elevator. The people hangout in the elevator, riding along a couple times, until they realize they might be in the way. Perhaps the weirdest part about the whole ordeal is when you enter an occupied elevator at the ground floor and most of the previous passengers do not get out. For a moment, you find yourself wondering why this crowd is loitering inside, why they are all smiling staring at the ceiling, and why not one of them is pressing a button for a destination in the building. Of course, you immediately discover why that is, as those elevator doors slam home and the laser yielding robots emerge.

Elevator’s Music, 2007

In our previous email conversation (if you don’t mind me reproducing part of it here), when i told you how i felt that your work was not so much about technology anymore, it has its own sculptural quality. You answered that indeed your work had transitioned from tech objects to simply sculptures, that it had been a very conscious effort. Why this transition? Did it occur naturally or it part of a strategy?

I feel like I have done a lot of maturing in my romance with technology and art. When I first met technology, I was completely dumb struck: amazed at the magic and the endless possibility of its applications. I spent years in this infatuation, happy to only use technology for the sake of technology. An old acquaintance of mine called it “technomasturbation”. In recent years I have become completely uninterested in this approach. In a way, the magic of technology has faded for me. Perhaps it is because I now feel comfortable using it in my art. Or maybe it is because the process isn’t as important anymore. Regardless, what is surfacing now is much more of my classical training in art, with an emphasis on concept, form, material, and design. I like to think that my new work is no longer about advancing technology, using the latest greatest technologies, or discussing the theory. For me, it is now simply about poetry.

No Cuts, No Buts, No Coconuts. Image by Patrick Flores

No Cuts, No Buts, No Coconuts. Image by Patrick Flores

I have this theory: when artists first recognize that they can use digital technologies in their artwork (I include myself in this), almost all of them get seduced by this magical medium. They end up making artwork about technology itself, probably because learning the process is such an uphill battle, drawing skills from so many different non-art related disciplines. When they talk and write about the resulting art they have made, they usually focus on the fine details, embellishing on what it took to make the work, what makes it tick, and what special technology they used. Whatever concept they had takes a back seat to this conversation. I see this in my students over and over again. Even the most gifted students, who are well versed in conceptual art, buckle at the knees when they realize the potential of the medium. Soon they too are reinventing the drawing machine (to my credit, I did come up with a unique design for my drawing machine rerun), the super-cool-multi-touch data remix screen saver, or the custom built, Arduino driven, LED matrix display they could have just purchased.

However, this is a just a phase. Perhaps we can see this as the techno-puppy-love stage of electronic art. I think most artists who continue to use digital technologies in their artwork will eventually find their way to a comfort level with the medium. Once there, they can refocus their energy on the poetics and concepts of art, not the tools. Certainly you see this in the traditional mediums. When a painter first starts down his/her path, they usually lose themselves in the process, obsessed with the paints, the canvas, and that funny looking fan brush. Only after some practice and discovery do they arrive at more meaningful subjects.

I think this techno-puppy-love stage also goes for the audience of electronic art. Since the medium is very much in its infancy and many people still have trouble accepting Pop art, I can see why most of the questions are about how the thing works, not what it means. Asking what something means suggests it might be art. Asking how it works keeps it safe in gee-whiz gadget land.

With the audience the transition period from techno-puppy-love to a real relationship is much slower, probably because they aren’t in the trenches with the tools. Perhaps this is why so many new media art fairs and conferences are still focused on showcasing the latest greatest technologies and less in the poetry found within it. Certainly that approach is a better marketing tool, considering that this technomasturbation is what the audience is thirsting for.

Thanks Fernando!

Fernando Orellana – At the Tone, Please Leave a Message is on view until April 1, 2011 at Texas A&M University-Kingsville.