A Practical Guide to Squatting is a very adequate title for a book that will teach you the skills of lock picking, show you how to craft a solar oven using a pizza box, grow a community garden, build a swimming pool in an open foundation or avoid arrest after breaking into a building. An adequate and provocative title thus. The handbook, however, will also give readers an opportunity to reflect on a practice that is too often attributed to gangs of drug addicts and anarchists ‘stealing people’s homes.’

Larraine Henning, the author of the handbook, reminds us that, in many cases, a squat is an emergency shelter, an habitat in a derelict building that has to be fixed, lacks electricity, insulation and proper drainage system. Just for the sake of my own enlightenment i had a look at the housing crisis in the country where i’m currently living and it appears that homelessness rates are rising. Meanwhile the Empty Homes Agency estimates that the number of empty properties in Wales and England amounts to over 930,000.

Larraine Henning, the author of the handbook, reminds us that, in many cases, a squat is an emergency shelter, an habitat in a derelict building that has to be fixed, lacks electricity, insulation and proper drainage system. Just for the sake of my own enlightenment i had a look at the housing crisis in the country where i’m currently living and it appears that homelessness rates are rising. Meanwhile the Empty Homes Agency estimates that the number of empty properties in Wales and England amounts to over 930,000.

Yet, it is now an offence to squat in a residential building in England and Wales and no other sustainable alternative(s) has been offered in exchange. The situation isn’t much rosier in the rest of Europe as the fate of an icon such as Tacheles, Berlin’s art squat demonstrated.

My intention is not to become an apostle of squatting but just to put the practice into a broader perspective. In addition, squatting can go beyond the simple need to put a roof over one’s head when it extends to experiments in socialism, architecture, and community. Think of the Open City in Chile, Paolo Scoleri‘s Arcosanti in the Arizona desert, Christiania in Copenhagen or the Grow Heathow community outside of London.

With A Practical Guide to Squatting, the author -who trained as an architect- also reminds readers that architecture is not only practiced by an arguably elitist sect of educated professionals, but also by the disenfranchised, the layman, the individual and the collective.

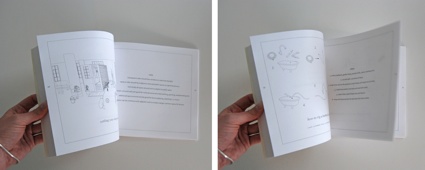

How-to make a swimming pool in an open foundation

How-to make a swimming pool in an open foundation

The book, alas!, is not out yet. It started as Henning‘s MArch thesis and she recently launched a campaign on indiegogo to raise funds for publication.

I’ve asked Larraine Henning, a ‘former architect turned fruit picker / illustrator / squatter / cattle musterer’, if she could talk to us about the book and her own squatting experiences:

Hi Larraine! How long did it take you to gather this very detailed information?

I worked on my Master thesis for nearly a year. The first half of my thesis was a research component where I investigated informal architecture, alternative communities, temporary building and squatting.

The the final product of my thesis was the handbook “A Practical Guide to Squatting”

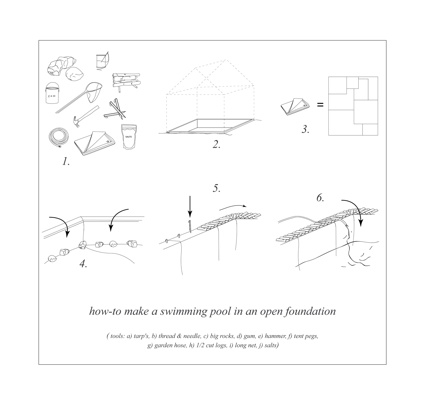

How-to pick a lock

How-to pick a lock

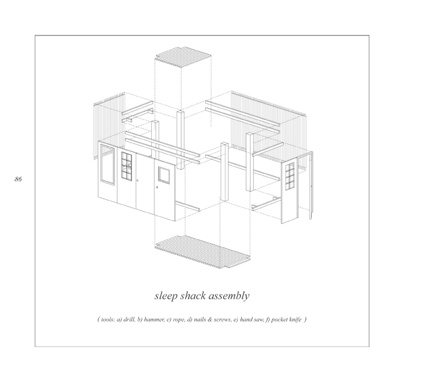

Sleep Shack Assembly

Sleep Shack Assembly

And how much of it stems from personal experience?

Prior to attending UBC in Vancouver I lived and worked as an architect in Rotterdam. For a short time I lived with my boyfriend in an anti-squat, which is a legal and registered version of squatting in the Netherlands.

We shared half a floor of a large office building in the center of the city built in the 70’s. The toilets were the former public washrooms for the building, we had the men’s washroom and the other lady we shared the floor with had the ladies’. We had no hot water on our floor and had to do all our dishes in cold water. There was one shower for the whole building (6 floors), which was rigged up to the only hot water source, that we all shared. No one paid typical rent, but paid the building owner only for basic utilities. Eventually everyone was evicted as the building was slated for demolition.

Since living in Australia this last year, I have occasionally lived in tent communities with fellow agricultural workers. This was not full on squatting, but it was on land that started out as a tenting squat until the woman who owned it organised a more set up campground.

As a young person I would often break-into abandoned buildings simply for the thrill of exploration. I loved to stumble around the wreckage of forgotten urban relics. I would do this in the city and in the countryside, and once slept the night in an abandoned cabin below a caved in roof in the middle of winter in the Prairies of Canada.

It was exhilarating and I hope I never get too old and crumbly to do stuff like that.

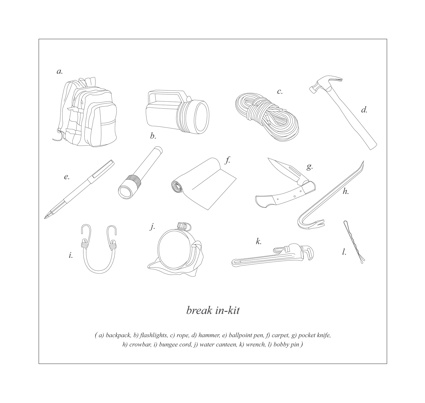

The break in kit

The break in kit

I was also wondering how you deal with the legislation? I don’t know about the (anti-)squatting laws in Australia where you now live or in Canada, the country you’re from but i know that anti-squatting legislation is getting increasingly strict in some parts of Europe. For example, the UK law now criminalizes squatting in residential premises, even if hundreds of thousands of properties are now sitting empty across the country.

Squatting is not really legal anywhere, however some countries choose to accept it more than others.The constitution of Sweden upholds something called allemansrätten, translated as “freedom to roam” or “everyman’s right”. Its decree claims that every person shall have access to private or public land for the purpose of recreation. The UK and Holland have a loaded history of squatting and typically condoned such living. Over the year their progressive attitude has dampened and it is becoming less and less acceptable. The laws in most countries however have loop-holes. Squatting really isn’t a matter for the police, but rather it is usually the job of the actual property owner to press charges against trespassers. Not until that happens do the police actually have the authority to take legal measures on squatters. Not only that but every country seems to have a different rule regarding abandoned property. In Canada a property needs to stand vacant for 50 years before it can be acquired by someone else and legally taken over. In Australia it is only 7 years, and provided you have not trashed the place but begun steps to set up camp after those 7 years you can apply to the crown to have the title put in your name, for free.

Can you conduct a family and professional life while being a squatter? Is it compatible with, say, getting electricity and running water installed?

Absolutely. Many squatters are working professionals and participate in everyday life just like anyone else. The place I lived at in Rotterdam was full of students, professional architects and the like.

The only difference is that you live in a home that ou don’t pay for and that does not belong to you, life can go on. Not all squatts have limited access to utilities.

Many do simply because they have been abandoned and these things have not been maintained. Sometimes there is a bit of work involved setting it up, doing repairs or building alternative sources for water, power etc.

You trained as an architect. Do you believe that architects should dedicate a greater amount of their knowledge and skills to squatting and other so-called ‘alternative homes”?

I think that people who worked in restaurants tend to be better tippers, just like people who lived without luxury tent to appreciate those small luxuries more.

I am not suggesting that everyone should give up the comforts of their home to go live in a squat, I do think that everyone, not just those practising architecture, should be tolerant and empathetic to how many other people live.

Thanks Larraine!

All images courtesy Larraine Henning.

Related story: Goodbye to London – Radical Art and Politics in the Seventies.